She paints distortion, vulnerability, and the psychic residue of history — Janiva Ellis on contortion as language and survival.

Janiva Ellis is a painter whose work stretches emotional and political registers through fluid mark-making, surreal juxtapositions, and animated dissonance. Her paintings contort and erupt, channeling humor, grief, and ancestral hauntings. She’s exhibited widely, including in the Whitney Biennial and at the Carpenter Center, and is known for refusing easy resolution.

She explains:

Why cartoon logic and slapstick pain offer the perfect language for distortion, survival, and historical violence.

How she embraces ambivalence by showing unfinished or uncertain work as a form of radical transparency.

Painting not to perform virtuosity but to let discomfort, exhaustion, and doubt remain visible.

Letting go of the “entertainer” impulse and choosing instead to rest, reflect, and resist institutional pressure.

How working through rage, shadow, and cultural projection allows the paintings to become psychological landscapes.

Why she paints for the terrain she’s in and how Germany, Berlin, and Kollwitz shaped one of her darkest pieces.

(0:00) NewCrits Podcast Intro

(1:34) Ajay Kurian introduces Janiva Ellis

(08:02) The Cartoon’s Burden

(17:00) From the Cruise Ship to the Studio

(24:30) When Whiteness Becomes the Subject

(32:00) Disillusionment and the ICA Show

(41:00) Exuberance, Masochism, and Recognition

(47:37) Working in the Dark: Technique and Intuition

(54:10) Letting Go of Control and Embracing Vulnerability

(1:00:44) White Spirals and Cultural Projections

(1:07:18) The Value of Communal Witnessing

(1:13:52) The Challenge of Raw Rage

(1:26:59) Dream Recall and the Fade of Intuition

(1:31:28) New Crits Upcoming Classes and Services

Follow Janiva:

Web: https://47canal.us/artists/janiva-ellis

Instagram: @janivaellis

—

Full Transcript

Ajay Kurian: Welcome to the 20th New Crits Talk. My name is Ajay Kurian and tonight for our 20th talk, we have Janiva Ellis here with us.

Janiva Ellis: Hey guys. Thank you so much for coming. There's so many people that I admire here and strangers who came because they care. So thank you so much.

Ajay Kurian: I'm gonna start with a little intro for Janiva and then we're gonna get into it.

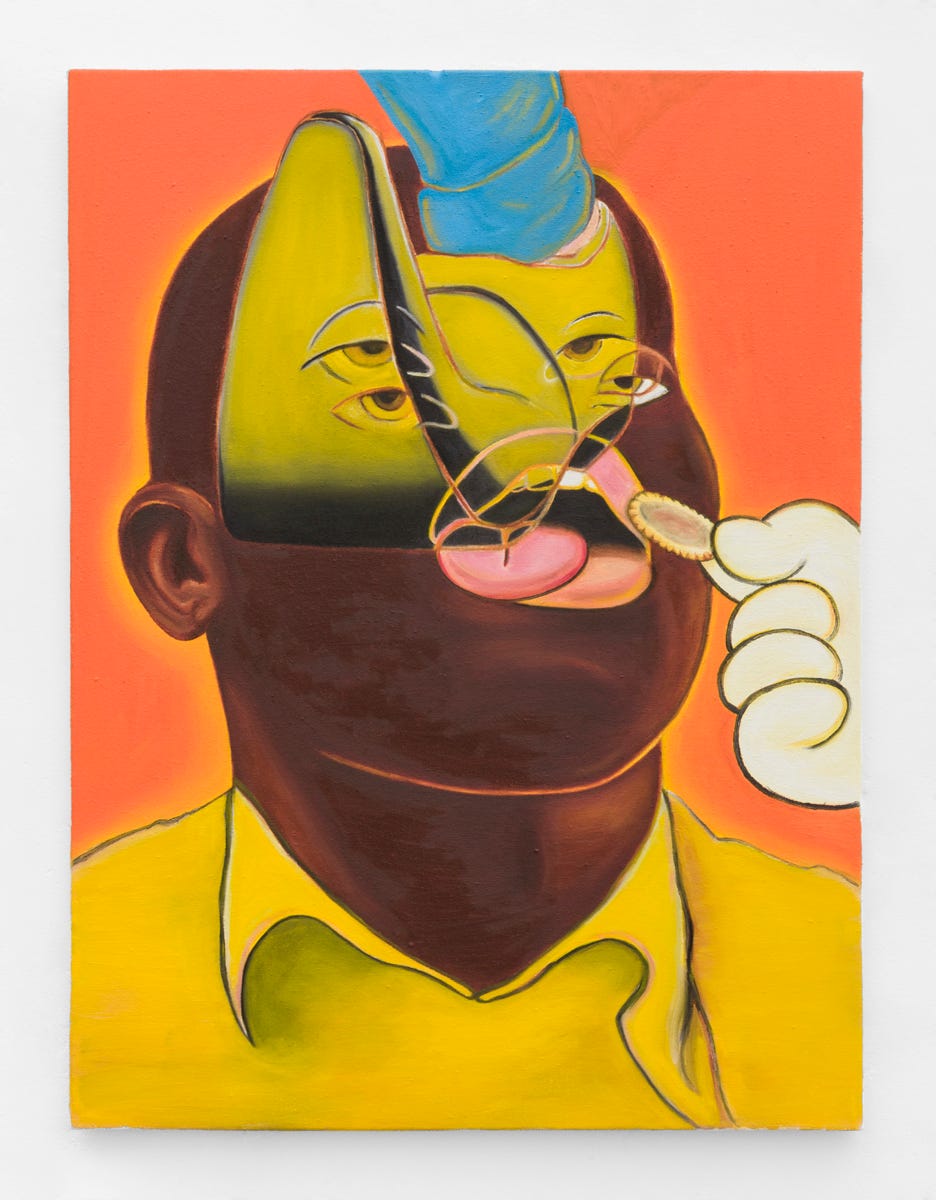

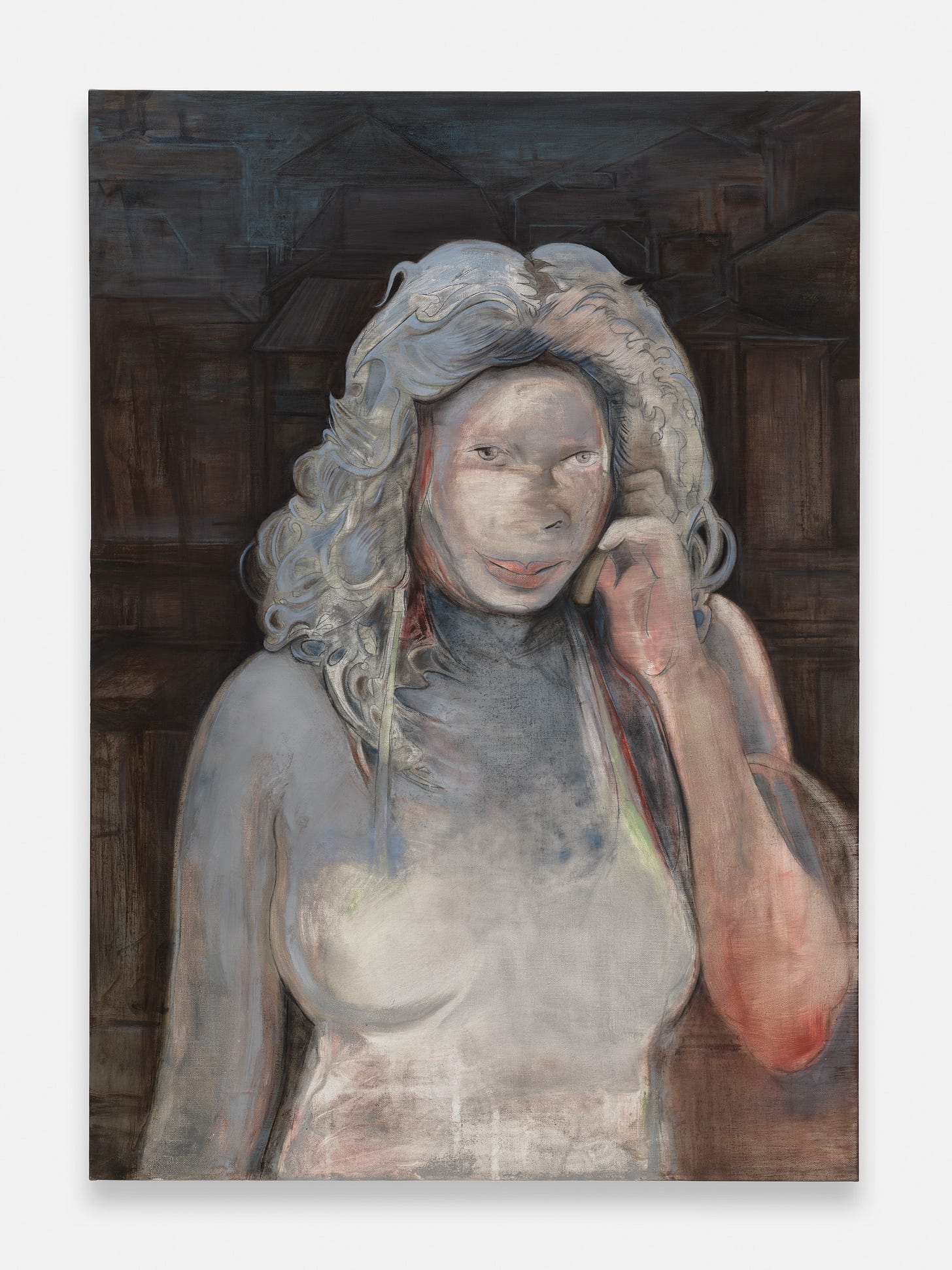

Sometimes when a person contorts themselves for so long, their reality itself becomes a distortion. If a person forgets their contortion, then the distortion is reality. More often than not though, somewhere deep down, the score is being kept - and that's what keeps it a distortion. The figures in Janiva Ellis's paintings are living in this wonky place, where contortion and distortion meet, where internal and social realities commingle and conflict.

I think maybe that's why she favors cartoons. Because they can stretch like an accordion, get blown up by land mines, and freeze or burn without ever skipping a beat. They are projections of contortion and distortion. The cartoon, despite its flatness, here acts as an echo chamber for history's emotional and violent contradictions. Meanwhile, a richly detailed illusionistic landscape may in fact be entirely flat - a visual lie that we've accepted as reality. In the interplay, Ellis is able to conjure vivid but slippery tableaus that weigh as much on the sociopolitical as they do the privacy of one's most intimate thoughts.

She is a skillful conductor. The haze is intentional; the confusion is part of the pleasure, and the finish is meant to be a question. She's an artist who knows how to simultaneously set a trap and set you free. Please join me in welcoming Janiva.

Janiva Ellis: You tore that, you ate that the fuck up. Thank you.

Ajay Kurian: It's my pleasure.

Janiva Ellis: Thank you for seeing the work. Thank you for confidently putting words to it, engaging with it, and not shying away from your assumptions about the work because they're really right on and it’s cathartic to hear.

Ajay Kurian: Thank you, I’m honored. It’s not easy to write or talk about your work. I don't know the dynamic of how I'm supposed to play it all out because it's charged, and I think in this conversation it'll be really nice to talk about how those dynamics stay charged and how they move and change throughout the work. There's been a lot of changes and that’s the reason why I wanna start with such an early piece. We're gonna start here and then we're gonna go all over.

The development is amazing. I don't say that often and I'm not blowing steam. It's rare to see an artist where every show it gets better and better. I'm genuinely astonished because when I saw your first show, it was great but I'm curious what comes next. I remember Tyler the Creator talking about Vince Staples’ album. It came out and he was like, this is it. But then the next album was the one he was excited about.

Janiva Ellis: Totally. Oftentimes in the studio, I've processed the idea, but I still have to make the show. I'm halfway through the painting and I got the idea, but then I have to finish the painting and I have to finish the show. But I cannot wait to take what I've metabolized and bring it to the next project. I'm on the hook for this project and I do need to finish this and get it out, but there's already so much enthusiasm for what I wanna say next. Then in the next project, I don't know what I'm doing. While I'm making, I know what future me needs to do until future me is present me, and then I'm confused again.

Ajay Kurian: How do you stay in it and how do you keep that same energy?

Janiva Ellis: I don't keep that same energy. I think it's an underlying drive. Sometimes I try and let the energy of the past project evacuate by taking a lot of space or creating interventions in the work that are challenges so that the part of my mind that's stimulated by problem solving is activated again.

I try and take what I've learned and I'll keep notes. Sometimes I don't even know what that note meant, but let me interpret it in the now and run with that thread. So it's not necessarily about holding tight onto the thoughts that happened in the past, but maintaining the same enthusiasm around my curiosities and my desire to feel challenged by what I can create.

Ajay Kurian: This painting is called the The Okiest Doke from 2017.

Janiva Ellis: One of my friends said “don't get caught up in the Okeydoke”. It's either DeSe Escobar or Juliana Huxtable, and it could have just been the community. It could have just been something we all said.

But it was very much a 2014 “we're out here” vibe. As with a lot of my titles, they come from notes I had taken about things I had said, or friends of mine had said on nights out about the predicament we'd find ourselves in and the joy we'd find in feeling like we were able to put language to this spiral we were navigating.

Ajay Kurian: It always feels that way. The titles catch a vibe. I understand it sometimes and other times it washes over you. But then you click with the vibe of the image, and you can feel that vertigo of where the picture takes you to.

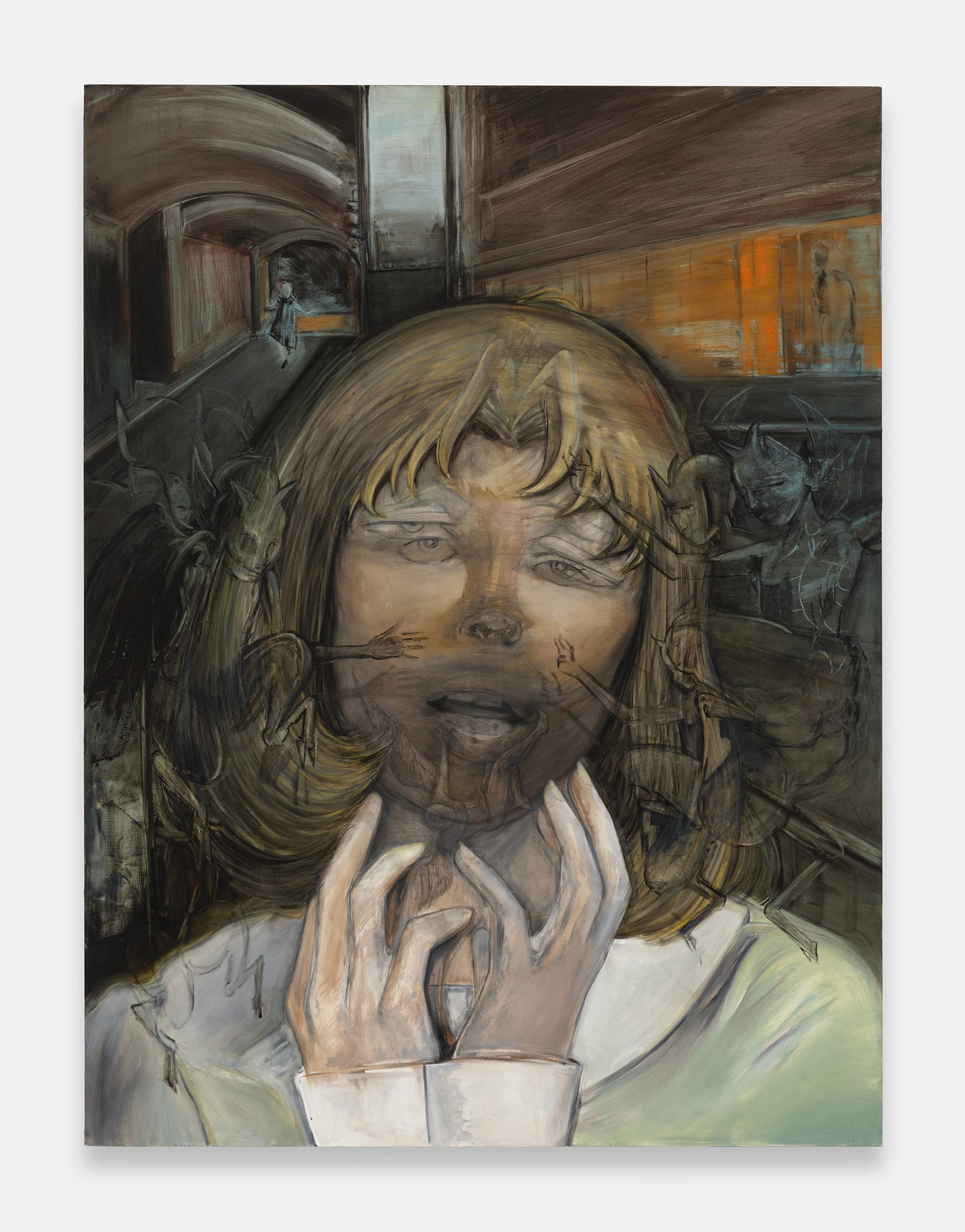

Part of why I wanted to start here is this cartoon hand. This communion into cartoons is an interesting place to start, and also how you continue to use the cartoon in the work. In my understanding, the history of cartoons is a pretty fraught one, especially as we get into Looney Tunes and all that. The precursors of those cartoons is essentially seeing blackface and minstrelsy turn into the cartoons that become beloved characters and then become these characters that never die. They can always be distorted, can always work harder, can always explode, freeze, do whatever, and just come to life again. For that to be the person who's giving the wafer here feels wild.

Janiva Ellis: This the cartoon’s burden. It’s like the burden of constantly having to endlessly embody a projection. When I started doing cartoons, it was literally out of the need for speed. I was taking my practice really seriously for the first time, and I felt a lot of shyness around pursuing what I wanted to pursue.

I really wanted a level of grandiosity that I didn't know how to achieve and I also had a lot of self-doubt. So I decided, let's just go back to basics. You can communicate the things you want very quickly and easily by cartooning, and you can re-access your hand and your ability to draw by using cartoons.

I think the fact that it speaks to the fraught of the way that white violence depicts blackness and the way that whiteness cartoonized black people was not the starting point. There's just so many moments where it was like, I'm gonna do this. Then the funny byproduct of that is that there's a critique to be had about whiteness. It's not the point, but oftentimes it's just there.

There's a painting I did of a woman and I made her into Pinhead. Then I did some research on Clive Barker, who made Hellraiser. But where did Pinhead come from? And it came from African sculpture and I wasn't trying to give that, but obviously it gave that, and as I was painting, it worked out that way.

There's violence woven through so much pop culture and so much of things I'm referencing from an organic place, from a place of resonance, that it doesn't take too much to connect those dots and I can just riff without trying to make a heady dialogue around blackface. It's already there. The history is there. Early on, people were asking me a lot about blackface and I'm like, yeah, that's inherently in there but I'm not trying to flatten that dialogue. I'm trying to create broader worlds for that representation to exist.

Ajay Kurian: Did you always trust your intuition?

Janiva Ellis: No, absolutely not. It's a constant moment to moment. I do feel really driven and I know that I'm strong, but I do also have doubt. There’s an underlying pulse that I trust, but topically I feel really disillusioned and really capable of falling for dumb tricks. So as I get older, I feel more capable and more self trusting. As the people in my life become reflections of who I want be surrounded by and the relationships I wanna see in the world — That really bolsters my sense of self worth, and that bolsters my trust in myself. But no, I didn't feel that way. Even when I started painting again after years of taking a break, I was like, what's the story there?

Ajay Kurian: How did you come to painting? Why did you go away from it and what got you back?

Janiva Ellis: I started painting as a kid and was always painting. My mom was very encouraging of me. Being good at something, finding what I liked and just doing that and finding catharsis in some way. So she's really supportive of that.

I did that for a long time and went to schools that encouraged creativity. Went to college and that evaporated all of the excitement and enthusiasm I had about the potential to make something meaningful.

Ajay Kurian: Did you go to an art school?

Janiva Ellis: I went to California College of the Arts in San Francisco, and the experience I had alongside school was so deeply enriching in terms of self-identifying and finding people that inspired me. But the school experience was pretty stale and I don't know if this is a broad thing or if this still happens, but I remember the idea they told you that only 5% of you are gonna be doing this for the rest of your life. It was very like, y'all are gonna be failures and compete for who can actually make this a thing.

Ajay Kurian: Oh, that's horrible.

Janiva Ellis: Yeah. Is that normal? Did people experience this in art school. That’s a thing, right? This idea that only exceptionalism will bring you fulfillment essentially, that was just the vibe. And then what I saw being labeled as exceptional, I was like, this is crazy, this is a bad art, what's going on?

But I also knew just based on the kinds of things I attracted in my life that I was able to actualize and I was capable of fighting a heartbeat in what I wanted out of life. So I did have that feeling, but I didn't know how to get it and I didn't have models of what that really looked like.

Ajay Kurian: But you knew you wanted to be an artist then?

Janiva Ellis: I did deep down, but I was open to a lot of options of what that could look like and how art would enter my life, through teaching or through programs. I wasn't like, I'm gonna be a successful artist. That definitely was not something I thought was a given or something I was striving for outright. It didn't feel inherently valuable to what I had to offer the world.

But it was there, and of course, I wanted to ultimately live a life where I was creating things that connected with people, and that I would have the respect of my peers and the respect of people who engaged with what I did.

Ajay Kurian: So your first show at the gallery and entering the art world — what was that step? This is a painting from that show.

Janiva Ellis: This was the first show. That moment was really a madness. I had gone to school, I had gone to New York, I had connected with people who I really felt were my people, I had crashed out, I went back home to Hawaii, tried to figure it out again. Spiraled deeply, decided to go back to the mainland, I grew up in Hawaii, so that's the context of that. I moved back 'cause that's where my mom lives and that's where I grew up.

That's the context that shaped so much of my perspective in terms of growing up on an island, growing up very isolated as a black person, growing up with an immense wonder of the world and also doubt of my environment. So that was a whole thing. When I moved to New York, I finally was like, wait what? Black community, that's crazy.

It was such a rich moment and the intersection of being like, I went to San Francisco and the queer community hit, now I'm in New York, it's black, it's queer, it's cute. So leaving felt really I'm abandoning, work that I put into finding my people.

Janiva Ellis: But Hawaii had its own healing intersection and I knew I couldn't stay there forever, but it was a good detour. Then I moved to LA and my friend Jesse let me stay with him, and said you gotta do this, come on, you should paint. He helped me get canvases and helped me get things that I needed. I was like up in the air and I didn't have a solid job. I briefly worked on a cruise and I had made money bartending on this cruise. So I had a chunk of money from that. And that's when I was able to focus on painting 'cause I had that little savings and these materials and I started to make paintings. Very quickly, I think the enthusiasm of being somebody who had lived in New York, but also the novelty of being from Hawaii. Like really helps in people thinking you're cool. Like people are like, we wanna know more.

Janiva Ellis: So that's an advantage. And I think when I got to LA, people were like, what's your deal? Or I've seen you around? I had spent some time partying in LA like years prior, so there was just some foundation there.

Ajay Kurian: This is a totally random question, but having worked on a cruise, would you ever go on one?

Janiva Ellis: No, I never wanted to go on one in the first place. The cruise I worked on was like a small Alaskan adventure cruise. It was a 60 passenger boat, so it was pretty intimate and it was freer, like middle aged to elderly, adventurous white, northwestern person.

Ajay Kurian: Oh, so this is just, this is straight classes for you — you were this is classes of anthropology and whiteness.

Janiva Ellis: It's all anthropology. It's like, this is how we're freaking it over here — it's data. It was actually a really crazy experience.

Ajay Kurian: I can only imagine. I've been on two cruises and it was the wildest experience.

Janiva Ellis: Did you see Sinners?

Janiva Ellis: I saw Sinners. I loved Sinners.

Ajay Kurian: Sinners is great.

Janiva Ellis: It's so good.

Ajay Kurian: We're going again on Thursday.

Janiva Ellis: Good. I want the second time hits.

Ajay Kurian: Oh, you've already seen it twice.

Janiva Ellis: We saw it twice. Are you gonna see it in imax?

Ajay Kurian: That's why we're going a second time. Because this is what's coming through for me. There's something vampiric here and there's something undead.

Janiva Ellis: They're like in the warehouse, having a good time. The background scene is from, The Wiz, A Brand New Day, and I put him on top of there 'cause I was like, I feel like with all the incredible black media that I've been exposed to, for some reason there's just like some white guy constantly in the center.

I think this early work, I was like, can we talk about this stuff? I feel like I wanna talk about these things. I didn't realize how maybe cryptic the work was being read. It felt so literal to me. In terms of just the tension of trying to thrive under white supremacy and microaggressions and all that.

Ajay Kurian: Who thought it was cryptic?

Janiva Ellis: Obviously non-black people, specifically white people. But the reflections I was having as I entered the art world were primarily through writing by people who weren't black or curating by people who weren't black. And I think, although I took that context into mind, it was louder. It just was louder than what I was, and what the conversations I was having with peers about the work.

Ajay Kurian: As soon as I saw this there, the energy it was giving was, whiteness is on display and it's gross. Like this particular variety of toxicity.

Janiva Ellis: The violence of it.

Ajay Kurian: There's an enormous violence of it that's happening on so many different registers too, right?

Ajay Kurian: Because there's overt things, but then there's the ways in which it shifts people of color’s visions of themselves. The internalized visions that people have of themselves is shifted by whiteness.

Janiva Ellis: The parasite of how you self ideate through whiteness.

Ajay Kurian: It's such an insidious space and it's very difficult to represent. I haven't seen painters represent that and I can't even actually think of anyone.

Janiva Ellis: Yeah, thanks.

Ajay Kurian: I hope it'll spawn other artists to think with it, but you're the first artist that I've seen that does that.

Janiva Ellis: I just saw the Jack Whitten show and it was such a relieving experience to see the course of the work. I feel like a lot of the artists who are processing this information or doing it abstractly, it happens a lot more through music, cinema, and abstraction. Safety is a part of that.

In terms of illustrating those sensations, it's not as common of a thing. It doesn't feel that safe to do that. And I think I just stopped caring. I stopped giving a fuck and being in LA felt like a frontier to not care. I had a really cute bedroom and that really helped me be like, I’m just going to do this.

I like what my room looks like, I’m around my friends, and I feel inspired because I've left Hawaii. I came back to people who recognize me and I have nothing to lose. But yeah, this is edgy, but is it that edgy? It's not that crazy to be this painting Doubt Guardian 2.

No matter how much you commune and how much care, there's always an internal spiral and there's always an impulse to make sure you're protecting whiteness even within the insulation of community. Or maybe not. That's a generalization, but that is something that exists. It's an anxiety. So I did want to articulate those things.

Ajay Kurian: I think it expands and you keep pushing. It’s this sort of emotional palimpsest.

Janiva Ellis: What does that mean?

Ajay Kurian: Palimpsest is when a there’s a page and then another page will just be put on top of it and be embedded into it. So in this case, it's like a face on top of a face on top of a face. Things just keep getting layered and pushed in. So like you'll see an ancient text where it's either an Egyptian text or whatever it might be, and there’ll be a new text embedded into it. But not so literally. There's an emotional world that happens when all of these things get projected and pushed into one being. What's beautiful about it is that it doesn't even feel like fracture, which almost feels easier. This is the blurriness of having them all commingled at the same time.

Janiva Ellis: It's like a lot of things happening at once. Reconciling how you're being perceived, how you perceive yourself and how you want to be perceived. Even the distance between how you are being perceived and how you want to be perceived is a lot to conceptualize. And then how you perceive yourself as like lifelong work and there's the immediate, there's the potential. There's the near future, there's the distant future, there’s the past. It's a lot of non-linear time happening especially when you're engaging violence. Especially microaggression relies on an ability and I think those things are really hard to name when you don't know yourself and you don't have the tools to articulate who you know yourself to be.

Ajay Kurian: This is the thing that strikes me as even more of a singularity about you is that there are artists that know how to not know. There are artists that make great work that their intuition takes into a place and they do amazing things. They don't necessarily know everything that they're doing because they don't have to and that's not what's required of them. What I find particularly astonishing about the way that you move, especially from conversations we've had in the past, is how you're able to articulate those ambiguities both in the work and then also in conversation. I'm wondering, is this is just me going out on a limb, growing up in Hawaii and being away from dominant conversations about race, do you think it gave you a way to see things that other people couldn't see?

Janiva Ellis: I think it gave me perspective because dominant conversations about blackness specifically weren't happening, but there were conversations about race and interrogations of colonialism and whiteness in Hawaii when I was growing up. Lots changed and it's quite different. The colonial project moves quickly and that's very apparent in what Hawaii is giving now.

But when I was growing up, it was still very appropriate to have verbal disdain for white people who had moved to Hawaii. You need to acclimate to this vibe and what is that energy? This is what we give here. There's still this kind of racial ambiguity, privilege and obviously white privilege, but in casual conversation it would just be ugh, that white guy is doing this thing.

Whiteness wasn't the predominant race. And when we're learning about history, we're learning about the recent colonial project. So I think that helped to be culturally suspicious at large.

I think in relationship to my removal from how race functions on the main land or the continental United States — I say mainland, affectionately, but it actually is a word we're trying not to say because it privileges the continental United States — But I feel like it gave me a perspective on certain things about how whiteness functioned differently there than it does in Hawaii.

Ajay Kurian: In this particular painting, is that cartoon invented?

Janiva Ellis: Things are rarely invented in terms of their structure. A lot of the figures in the work are armatures from different movies, cartoons, or landscapes. I rarely really make a character wholly from scratch.

Janiva Ellis: There are inventions in how I navigate ultimately how to get to a finished product, given my shortcomings and my strengths. But which character are you talking about?

Ajay Kurian: The red-haired white character.

Janiva Ellis: The white character is from a Ralph Bakshi movie. I think it's from Heavy Traffic and the character in that movie is really vulnerable. Have you seen heavy traffic?

Ajay Kurian: I haven't. I've seen Fritz the Cat.

Janiva Ellis: I actually haven't seen Fritz the Cat, but Ralph actually made these movies in the seventies that were pointing at racial tropes. But they also felt very, when I first saw them, I was like, oh a black person made this. When I found out a white person made it, I felt betrayed. It’s such a thing because now I have to reframe this, 'cause I enjoyed it. But yeah, he made this movie about New York and about racialized dynamics. He's the main character.

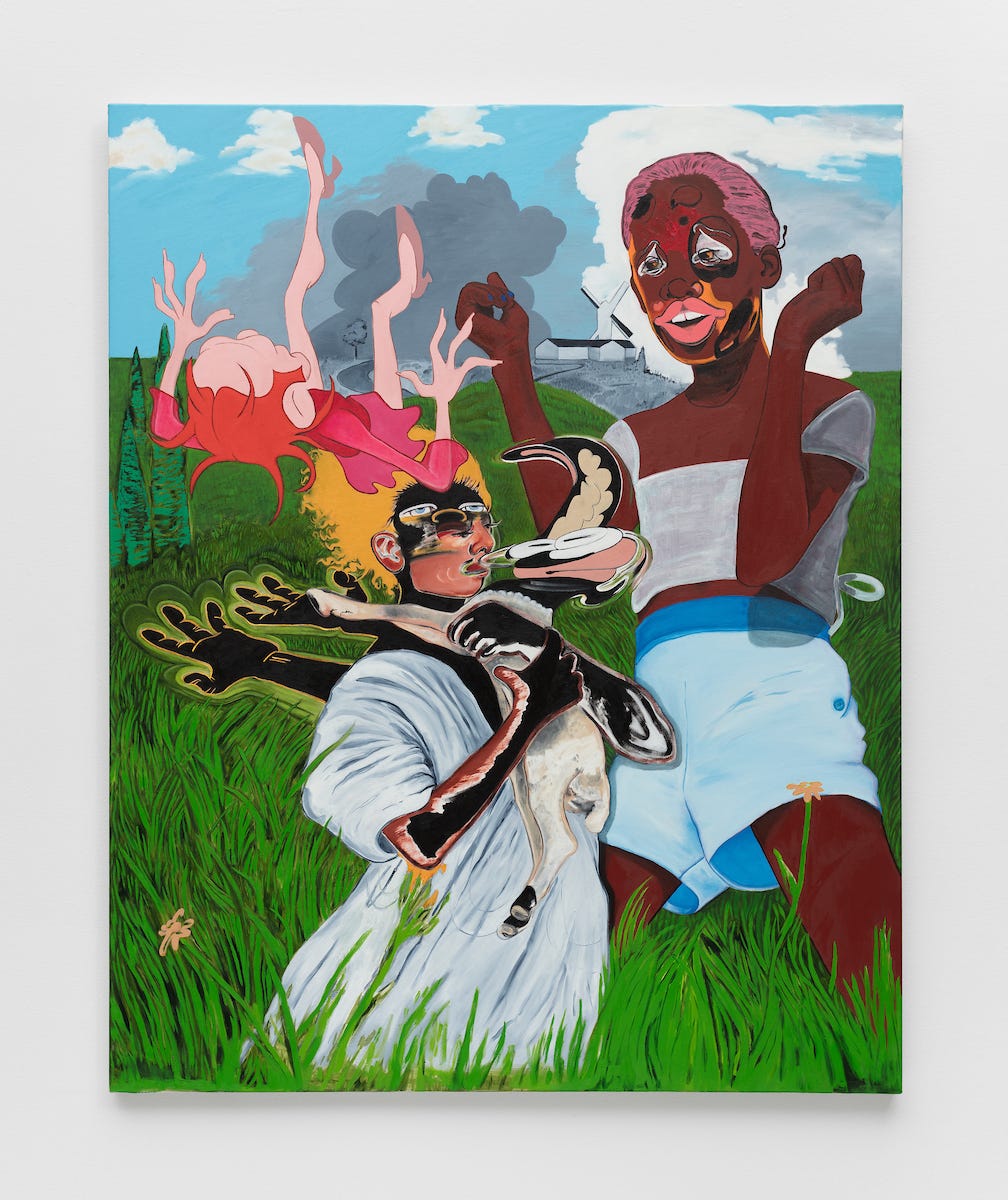

Janiva Ellis: There's this black girl who works at a bar that he likes and they have a vibe. There's this trans femme character in the thing that's based on her. So I didn't wanna literally be like, this is narratively about that, but that image of her flying and being knocked upside the head, she's incredibly vulnerable in that moment.

Janiva Ellis: And the image itself was really striking 'cause this is injustice, representative through this cartoon. But also there's something about how the interplay around white fragility and blackness is creating a net.

Ajay Kurian: These are conversations that continue in the work. I'm gonna shoot ahead now because that made me think of this painting.

Janiva Ellis: Really different. A lot changed. I was really distrustful of the exhibition landscape in art and so much of that earlier cartooning work when being pretty explicit about black figures experiencing like subjugation or the kind of illustration of some turmoils or frustrations or the complexities. I made that work in earnest in my studio thinking about connecting with other black people through that work. And as I got deeper into the art world, I realized that that impulse was being manipulated by the agenda of the art market at any given moment.

Janiva Ellis: So I was feeling pretty disillusioned, frustrated and angsty about not being able to freely access the things I was doing. Early work just happened so quickly and so fluidly; I’m gonna project that, and I’m gonna watch that movie, and that ties to that, and these narratives feel so interconnected. I feel like I can see it so clearly. But as I experienced more writing about my work, more conversations with respectable art people, it got cloudier and cloudier. My studio was full of people who I didn't like mentally, And I was just like, how do I do keep doing this and enjoy it? How do I take control of what's going on?

Ajay Kurian: So on the one hand, there's who you led into the studio and who you led into your life.

Janiva Ellis: My studio's full of people like psychologically, I'm spiraling, so people aren't actually in there physically. Sometimes, sure. But primarily, it's like I'm painting with chatter that didn't exist before.

Ajay Kurian: Chatter.

Janiva Ellis: Chad.

Ajay Kurian: Chad just seems like the whitest name to me.

Janiva Ellis: Chad's in there, but it's not like Charles. It's Chad’s coming.

Ajay Kurian: It's maybe Alex or Brad.

Janiva Ellis: Devin. You know what I mean?

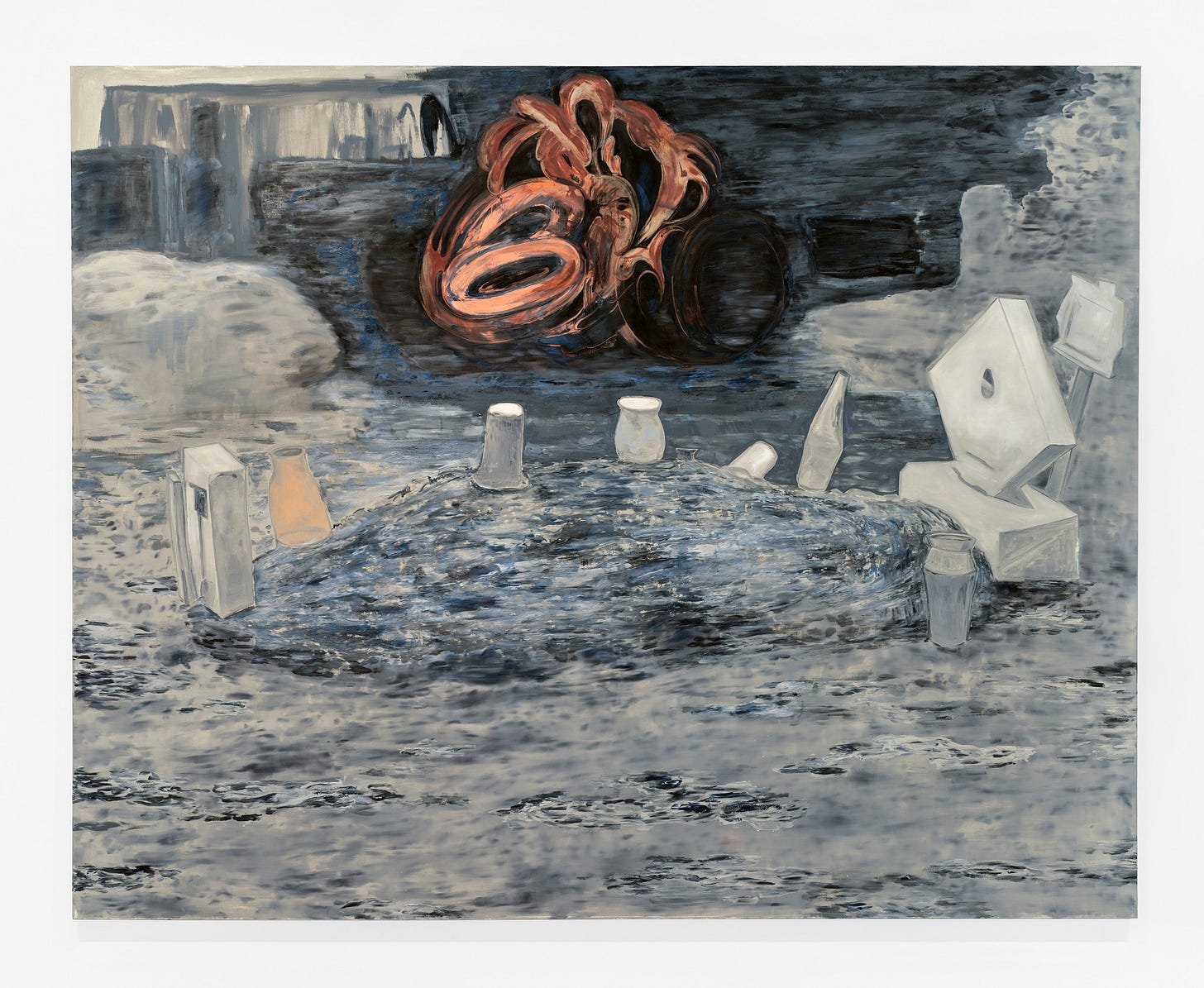

I think my radar for discernment recalibrated in that period, and specifically with this rat show at the ICA, because I had a very tense experience making the show with the institution that I just wanted to be like, I'm just gonna talk about whiteness. I almost wanted to be like, I'm not doing black figures, but I was like, that still feels oppressive.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, that's just the opposite side of the coin.

Janiva Ellis: And I'm just inverting things and I do wanna make these cool images, right? I do wanna make these exciting compositions, and I still wanna represent the things I wanna represent. But I had more of an impulse to contrast that with images like this.

Ajay Kurian: The reason I bring this up also is that this was based off of a Walker Evans photograph where white precarity and white victim hood are established in this long photographic project where Walker Evans and James Agee go through into the South and they document white sharecroppers specifically.

I know those images and I know that book, but the twist here, I think is under you creating a place in which the hidden violence of starting that conversation is brought to the fore where there's a very neutral landscape. Even if you don't know Walker Evans, even if you don't know all of that backstory, just as an image, there’ is a landscape with the grave. You don't know who the grave is for, but you do see something roiling in the back…

Janiva Ellis: Roiling. I like that .

Ajay Kurian: …That fucks up what you're supposed to be paying attention to. So something is central, but you feel like the thing that is supposed to be central isn't?

Janiva Ellis: Like the sensationalism of a representation of death is complicated by an ominous abstraction.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah. That's not easy, ’cause it can easily fall into illustration. It can fall into you not paying attention to the right thing. You have to think and it can become this preachy discourse. But instead, there are two things for me that felt like a big jump in your work, one being the color palette getting like dark.

Janiva Ellis: Murkier, yeah. There are voids created by the lack of vivid color that I was very much pushing really hard. I think in the midst of also being a figuration, all of this feels like an advertisement for engagement.

I don't want my work to reduce itself to style and to repetition and to pushing buttons I know work. And I think color was one of those things that people was an “out” for when people would write about the work. They would would lean into the cartoon and the color as a way of not talking about the racial dynamics.

And I was just like, y'all what? That's key. They're cartoons. Do you like cartoons? It's who fucking doesn't? That's not the point. Especially in that moment where black figuration was becoming so lucrative in the marketplace. I just was like, this is feeling disgusting and I don't want to advertise the value of my work through people's low vibrational impulses.

I don't want like them to be like, I like colors and black figures. I was just like, I'm scared. You're scaring me. You're stressing me the fuck out. Actually, let's flip it around. This is about y'all and y'all's history and the self ideation with vulnerability and entitlement to ascending to your highest version of yourself no matter what. Because in the 1930s everyone was poor. That feels like a big part of white American identity. Everyone was poor in the thirties, like as a fallout of slavery and like the, war and all of these things. And that's like an entitlement to be demonic. And so I was just like, let's just paint that out. This image feels like a representation of that painting is called Blood Lust Halo.

And this one ‘cause that's also Sinner's energy, like it is just a justification for a death drive. Because of an abstraction of precarity, as represented by Walker Evans and Dorothea Lang. These images of wow, look at these poor white people, there’s dirt on their faces. There's so much dirt. I just wanted to be like, okay, let's center that.

I think also in the moment I had that show in 2020, black death was just such a topical hashtag, right? And so I'm like, let's talk about death as a concept, and what white death represents versus, I just try and stretch that a little bit instead of illustrating black precarity for thirsty rich white people.

Ajay Kurian: Were there studio visits where those people would be in the studio?

Janiva Ellis: Not during the time, thank God, because of Covid. But also, I had a full mental break and was like, I don't fuck with any of you. I don't fuck with this. I was feeling very appeasing coming in. So I had a lot of room, even though the work gave anger, the presentation gave appeasing and in service a little bit.

Ajay Kurian: Before we go too deep into this, there's a shift, let me see if I can find that painting.

Janiva Ellis: I do wanna talk about this painting though, 'cause I love this painting.

Ajay Kurian: It's a great painting. There are paintings from this period that feel like they're tapping into a space that feels unclear between joy and hysteria and also masochism.

I see those things like not being fully removed in the work that's more recent, but they shift and they develop in different ways. But I wanna see what that brings up for you. I kept thinking about when you smile so hard that it hurts there's an internal kind of masochism happening there.

There's so much of this first period that feels exuberant. And it’s a challenging form of exuberance, ’cause it's not clean or simple or easy. It's difficult to figure out how a viewer's supposed to feel about that exuberance. And that tied up with all these kind of naughty issues, all this psychology that can't resolve itself.

Janiva Ellis: The exuberance was so sincere because I was feeling so much catharsis from just painting and I was experiencing a recognition from my peers about the depth I had. I think I wasn't even being forthright about the depths of my thoughts in certain relationships. Even though I knew people knew they were there, they took them for granted. I think I just was like, I have this other world in which these ideas can live. I think taking for granted isn't an extreme, but I think I wasn't being reflected back.

So I was just really excited. That's where so much of that excitement is coming from. I was making myself laugh and I was having a blast with myself in a really sincere way. It’s funny because there's a different type of fraught in these paintings than there are in the later paintings. The later paintings are existential in a different way.

Ajay Kurian: Very much.

Janiva Ellis: A painting like this happened so quickly. I constantly think of this painting as, how do I make a painting that fast again? That feels really exciting and a breakthrough of sorts with like the potential of paint. What I'm doing now I think is like a little more technically muscular. But I don't think it's better. I think it's focused on a different skillset and a different set of values and a different type of depth. This felt immediate, I don't even have to think about it that deeply. It just came out.

Ajay Kurian: It's an amazing painting.

Janiva Ellis: Thank you. I appreciate that. I really felt cool.

Ajay Kurian: But now let's go back. So let', start diving into these darker — actually this project feels like where you fully embrace this next chapter. And embrace what it means to think about history painting in a new way. It also makes me think of even Renaissance painters, like Titian, where they're dealing with the architecture. They're thinking about what the architecture means and how that functions in the work itself. This is a crazy painting. I wish we could like, see every single part of it.

Janiva Ellis: Thank you.

Ajay Kurian: Sorry, it should be darker.

Janiva Ellis: It’s hard to photograph. It's a hard picture to capture for context. It's 30 feet in a curve. So it's meant to simulate like an immersive panoramic type of experience. For context, I made this painting in Berlin.

So I think that did contribute to the decay quality. But also, I worked with this curator who was saying it would be cool for you to do a site specific panoramic type of painting. And I was like, okay, I could do it. We've got four months, but I can do it.

And four months was really quick turnaround. But I was like fuck it, I wanna do it. This room had been built by the Armand Hammer, the Hammer Museum.

Ajay Kurian: Isn't that the actor?

Janiva Ellis: No, that's Army Hammer. Tomato, Tomato. Bleak, dark, scary people. But I think this room was built to house some great Da Vinci work. Some special historical context and so I was thinking about that specifically.

There's a painting I did recently that's in the show at the Carpenter Center, and it was also in my solo show in September. I learned a lot of techniques about creating value in dark, muted tones. And like really going dark to create depths by using sheen and subtle variations in muted tone and umbers and blues and things.

Janiva Ellis: Can you pan?

Ajay Kurian: We'll pan. We're gonna start over here where this kind of barren architecture happens. We'll turn the lights back on in a second, but I just want you all to experience this so you're all with us.

Ajay Kurian: and then much better

As we pan you’ll start seeing value differences too. You start seeing these distinctions between warm and cool with the exterior and the interior. I'm not even sure what the relationship is between the angel and the other figure. Almost like that angel is wrestling with themselves maybe.

Janiva Ellis: Yeah, that one, the contorted, they're all going through it. They're all going through it. None of them are in a good place for different reasons. This spinning was interesting just because there was no natural light in the room it was exhibited in. But in the studio I had like this big, sunny room. The way that it changed with the spotlight versus how I was painting it in the sunlight was such a wild kind of set of circumstances. There was just a lot of journey happening like that.

But a lot of these figures are taken from different artists. This contorted figure is taken from Kathy Kitz, who's a German painter or a print maker, who I really loved before going to Berlin. I happened upon a museum dedicated to her and got to see a lot of her prints IRL. But this is based on a print she did of a figure that had been attacked in a field.

So I was like, let's do a German context and scoop it in. But I was also just so deeply affected by her work, her approach, and her ability to capture the path of just like the violence she's like depicting. It's just so masterful and stunning. And I didn't really learn about it until 2020, didn't really see the work, so I was just so deeply impacted by it. So I wanted to just shout out and put it in.

Ajay Kurian: I love that. You should really see the work. It is incredible.

Janiva Ellis: The technique and the poetry of how she's depicting figures is just really special. I think I was in a place where I was like, how do I access this German thing, like I really do paint for the terrain that I'm in and I brought it to LA to show. But I did want it to feel reflective of what looms over Germany. What looms over people who go there. To feel freedom.

Ajay Kurian: It definitely has a European-ness to it. Have you seen the movie White Ribbon?

Janiva Ellis: No.

Ajay Kurian: Directed by Michael Henneke. It’s this weird, creepy, black and white film of right before the war, and you can tell that it's coming and the kids are all fucked up. They start pulling these pranks that get more and more dangerous and more and more deadly. It’s like a lesson in how you can show the most quiet forms of violence and what they're about to turn into.

Janiva Ellis: Was the movie made before the war or the movie was set before the war?

Ajay Kurian: Set.

Janiva Ellis: So it's contemporary?

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, he’s alive. He's so good at quiet violence. It's terrifying.

Janiva Ellis: Put me on. I'm so curious. I love the quiet violence and the ability to reflect in that way and be like, how do we depict this in a way that translates the terms of a moment.

Ajay Kurian: This feels bigger than a moment though. I think there are times when the works feel potent and charged in the moment. And then, especially the more and more recent work, it feels like you're broaching larger swaths of history and different kinds of reservoirs of feeling, in a way.

Janiva Ellis: Definitely. The older stuff was that moment when you're out here and this happens, and it was trying to do some broad sweeping stuff, but in a more kind of scratching the surface in a different way. It still might not nod to sweeping eras, but in a way that's very plucky.

Ajay Kurian: These are great words.

Janiva Ellis: Yeah, this is a different tone.

Ajay Kurian: I'm glad we all experienced this together. Now when you see some darker works, we're not gonna keep turning the lights off, but now you know the register that we're dealing with.

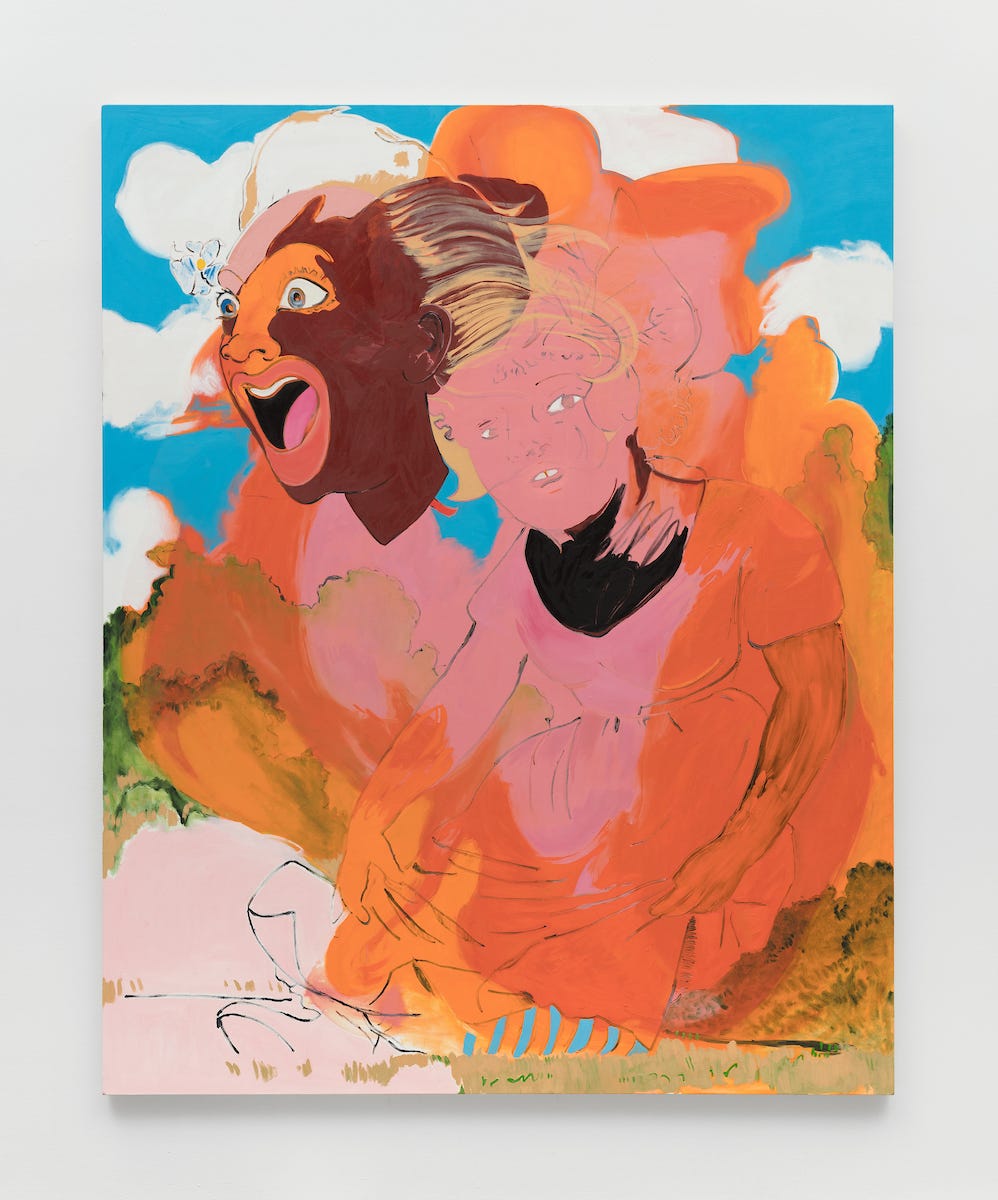

Ajay Kurian: We'll open it up to questions soon, but I think let's go to the most recent show. I want to go into the Carpenter Center Show because there's a new level of vulnerability.

Janiva Ellis: Vulnerable in a different way.

Ajay Kurian: I think I just wanna give you the floor for that. I don't know what got you there. I don't know what made you say, I want to show this even though I don't know where it's at.

Janiva Ellis: I think honestly, the dialogue I was having with Dan, the curator, I think made me feel comfortable to just try something and try a different approach. I think the impulse to be vulnerable in a school setting was that I was empathizing with how students engage with professionalism. And the pretense of Harvard is this exceptionalist projection and it just seemed important to be vulnerable about what it takes to get to a goal.

And how self-doubt is not an inherently embarrassing quality to have. That perseverance looks a lot of different ways. So when I was thinking about students seeing the show, that's really what inspired me to be like, I'm gonna do a massive studio visit, basically. Not try and say, here's this. Institution, let me flex some exceptionalism. And in all honesty, I was tired. like that also is part of it. It wasn't purely motivated by that, but I think it was a moment where I was tired and I'm not going to put myself into overdrive the way that I did for the hammer painting.

With this show, there's a moment for me to show a bunch of work that I don't quite feel confident about. I still tried to finish everything and I still tried to create a level of resolution with all the paintings in that show to the best of my ability.

But I didn't psychologically tap into the stamina required to set off the fireworks. I just let each painting be a different work and not try to really do the entertainment that I strive for in my work. This is not an entertainer moment. This is a vulnerability moment.

Ajay Kurian: It makes me think, you can say if this is an incorrect metaphor, but there's something about it that feels like what a stew is like half done. Like t's done, but you can cook it down further. It can cook for another three hours, but everything's there.

It's offering something in that moment where some things are still fresh, some things are still building, and you can see all of that happening and it makes me think that this gets to be this really beautiful moment that we get to see what's cooking.

Janiva Ellis: There's something between my last show in September and this show, there's something simmering here. But it doesn't need to be a moment that is an era. I do treat a lot of shows, like an era of thought and an era of my studio.

With this, it didn't feel necessary to approach it that way. I also just really wanted to access the feeling of being like, I'm shy about this work, but I'm allowing people to look at it. And it got the most press anything I've ever done has gotten.

I don't feel confident about all this stuff and it's like on full display. But it felt like an interesting emotional challenge to just be able to be showing things that I would never want the public to see. Some of it, yeah. Some of it I'm like, I'm not like embarrassed but I just think there's works that isn't indicative of capacity.

Just overriding that little goblin and being like, I got this. It's fine. It's whatever. You got this, I'm out here figuring it. We’re all figuring it out. There's no exceptionalism. Every day is different.

Ajay Kurian: No notes.

Janiva Ellis: Dan's fab. Dan, who's a curator I worked with, he made me feel incredibly comfortable. The approach I have for this show versus the show at the ICA are different dynamics.

Ajay Kurian: This is getting to that fireworks level.

Janiva Ellis: It's so funny because I struggle with this painting. It felt so just on the nose or something, and I'm not saying this isn't good or whatever, but I've been here before in terms of the themes. I think that's where the self-doubt came from this painting. But a lot of people are like, oh, this painting is going in. And I was like, oh okay, I have a new entry point for this type of portraiture and I don't quite know what it is.

Ajay Kurian: To me, there's still a shift. I see what you're saying in terms of you having been here before. But the way that you're treating it is very different. When we think back to the first painting that we all saw together, there's definition, there's clarity, and the way that you're even putting an image into an image is one where it's still graphic.

You've abandoned certain graphic sensibilities towards something that feels much more ambiguous, blurry, actually, and metaphorically.

And yeah, there are times where landscape shows through the figure. You can see that cloudy blue sky and it's like through the figure. But here it might be landscape, it might be tonal, it might be internal, it might be external. It's much more difficult to discern what’s what.

Janiva Ellis: How the layers are happening and what's creating distinctions.

Ajay Kurian: You’re pushing and pulling in a new way. In a way that’s, in some ways, more sensitive and other ways you're just trying something else. It's a different register to me. So even though it might be familiar, because it's like the portrait centering this white woman in this way.

Janiva Ellis: I think I was like, okay, the white girl's spiraling. You know what I mean? Like what more could be said about that? It was a painting I needed to make. The reference from this painting is Sallow. It's like a zoom in on the girl. If you guys haven’t seen Sallow, it's this movie about fascism and these young white kids are experiencing degradations that are really extreme and so over the top. Degradation — it’s what's the worst thing you could think of that happened?

Ajay Kurian: I have so much to say about that, that's like a whole other spiral.

Janiva Ellis: Oh yeah, this person is really being subjugated in this image. Reducing it to something in my own context, can be read a lot, can be attached to it through how I'm talking about whiteness in work.

I do like to push through that ambiguity of we're still all human. This isn't trying to downgrade like violences that people at a human level experience. But here are the images we've been giving to value and what do we do when we manipulate them and recontextualize them. We don’t need to degrade them or make them feel like less potent. But what if we reframe them and what do they mean and what do they say about us culturally and what we prioritize?

Ajay Kurian: Prioritization, I think maybe is also the register that you're hitting right now. You can move things forward and make it clear and move things backward and blur it. It allows for different and new distinctions to happen. And for us to think about our own priorities and think about what we've been paying attention to. It's not to say the human picture is vast and always overwhelming, but we focus on what we focus on. What are our associations?

Janiva Ellis: What does it trigger when we look at different things. We're gonna all have different kind of entry points and familiarities, and those are just as much a part of the work. That's what art is, the communal experience of it. Not just the cathartic an artist has, or the dialogue two artists have with each other, but the witnesses and the people who make meaning of it for themselves.

Ajay Kurian: I'm gonna open it up to questions

Janiva Ellis: On that note.

Audience Member: First and foremost, thank you so much for giving us your words about your own work. This is a great opportunity to, I think, dive a little bit deeper into your process and your history. I think the first question I have is a lot of your pieces are not framed. Is that an intentional decision that you make?

I feel like the evolution of the frame gives an opportunity to add an even deeper layer of three dimensionality to your work as a sculptural element that could potentially add more to the narrative that you're trying to portray. So that's my first question, why no frames?

Janiva Ellis: I do love paintings as their own object and I do love like them as this is a flat space. When you look at a complicated image and you go deeper and you build a world, then the depth is there. I do love that just existing on a surface that you can walk around and see the side of it. Then there's like a brush stroke on white or like a smudge and a fingerprint.

The evidence of the evolution of an image is just really interesting to me, as you can see in other works of mine, where you see this looks more finished, this is abstract. Is that done? Is it not? I do the process being pretty transparent even when there's like a level of polish. And so that edge is something I like, but I'm into frames too. Sky's the limit for what something can be like and how it can impact people. It just hasn't organically come up.

There's one painting in the Harvard show that has a white frame, but I found that canvas on the street.

And it was already a painting and I painted on top of it. So it has a white frame, but I was like, oh, maybe I would make these really simplistic white frames because they do a different type of thing.

Audience Member: Thank you. Lastly, the first time I saw your work was at the Whitney Biannual, Uh Oh, Look Who Got Wet. In that moment my world shattered. So if you could just talk about that painting a little bit more.

Janiva Ellis: That’s nice to hear, thank you. That was a doozy of a time and there was a lot of chaos at that time.

Uh Oh, Look Who Got Wet is a lyric from a little ugly Maine song, who is a white rapper who pitches his voice down to escape his whiteness. And it just felt appropriate. I had already been painting the river. She's running through and she's trying to figure out. I was thinking about, do I go literal? Oh, look who got wet? Give you're in this shit now. There was a lot of controversy swirling around that show. But that show was in 2019 and my first exhibition was 2017. So within two years or less, I was really catapulted and responsible for a certain discourse in art that I wasn't ready for.

I was like, dang, uh oh, I'm responsible. So that was in there. But also I was like stealing and tugging at this little ugly thing. Then the imagery itself, I think is, the conflict of being responsible for something that is haphazard and oblivious. Being in crisis as you move forward and as you're propelled and driven to keep going.

I'm just gonna keep doing this thing, but I don't know what I'm doing. And I also am holding this thing that presents itself as vulnerable, but is shape shifting and chaotic. A critic wrote about this work and said that a slave runs to freedom, which was so painful and telling, because it just said, oh, this is where we're at.

This person just confidently is like, this image of a black figure running is like about enslavement to a degree. It is, but not in the ways obviously that she was framing it. It is about being beholden to things that don't serve you and making choices about what you need. But I also wanted it to be like a cinematic freeze frame where you're like, where is she going? What happened before this? What's happening after? We don't know.

Ajay Kurian: Thank you. There's a Steffani Jemison video that also feels relevant. Where it's an ongoing panning shot of a black man running. And you don't have any context, but what you start projecting onto that man starts telling you about yourself.

Janiva Ellis: Exactly. The projection is so much of work, especially in these contexts, in these institutional spaces, it does have to be acknowledged that these are in the context they're in. Even if they're made for an audience that is not actually represented in that space or is not centralized in how the work is framed by institutions and journalists and curators.

Audience Member: Hello, my name is Anna, and I love the way you openly speak about your feelings. Every time you describe a painting or a project you would work with, like you mentioned, I felt shy, but people loved it. So that's cool. And then the other image and you go oh, I was so happy. That was joy.

But my question is, do you have a specific painting that you felt like was a challenge? Something that you had to face at some point, because it's fantastic that you actually acknowledge your feelings and you are aware of even you don't trust your intuition, but you still just know what you're doing.

Janiva Ellis: I'm glad you appreciate the transparency. I'm glad that's resonating. Do you mean paintings that are hard emotionally, or the existential emotional way and reconciling what meaning is being produced from that work?

Audience Member: Yeah, but not only meaning. Even to put it on the canvas and be like, am I afraid of it? What is your relationship with the painting? Not how other people would react, but your own feedback on, what the fuck did I do right now?

Janiva Ellis: I find rage, raw rage, scary and hard to be transparent about, in art and in life. Not couching my emotions and humor is something that's I'm working towards. I think humor is really useful. I think it serves a purpose. And I do feel like an entertainer at times with what I do. I want people to engage. I want there to be a range of emotions.

Movies are what motivate me. Music is what motivates me. Time-based art is the thing that I am most impacted by. So to be working in a static practice, I really want to have that arc in that range, which is why I try and incorporate the violence and the humor and the levels of finish and all of these depths and the things that are coming out. But raw rage, flat rage, punctuated emotion that is not embedded in skill and playfulness is scary, but I'm curious about it.

Audience Member: Hi, Terry here. I guess my very first impression of your work was that it's thought provoking, but it provokes more than just thoughts. It provokes feelings and emotions, and throughout this talk, something that came up a few times, was intuition. You mentioned earlier that there was a journey for you to maybe get more attuned to that intuition. And since the theme is based on distortion and contortion, I was wondering how that could play a role in your intuition or intuition in general as an artist? How you're able to distinguish between the noise and the distortion that could potentially interfere with, intuition itself. And again, as an artist who's trying to create, there must be things around that inspire you all the time. So how do you filter?

Janiva Ellis: Yeah, there's so many options. The wide range of options in which to pursue and the roads and the threads to go down. There's so many ways to freak your art and make something happen. And do I go this way? When I think about music production, I'm like, you could do this, it could be this, it could be fast, could be slow, there’s so many choices in music production.

I'm like, how did they get it? I find that so inspiring. But the way that I paint, I think about those things like the pitching up and the pitching down, and the slowing down and the reverb of all of those kind of moments when I'm just gonna blur that and then I'm gonna make that really crisp.

I think I had a really solid foundation of, and broad array of influences at a pretty young age. And this isn't the only way that this happens, but I trust my take. I think I have cool taste. I don't know, I like my taste. So I think that gives me faith in what I do.

I feel like the palette that I have has attracted people that I admire deeply and that gives me the confidence to pursue my intuition and explore. And, the stakes are low. In terms of following threads, that's not quite what I thought. It doesn't come out on the first try. Like that painting where I was like, that happened so fast and I've been trying to get back there. A lot of paintings are dense and have a lot of depth because I've tried 15 things and committed to them and had to commit to them not being there. It is a lot of trial and error, but it also is I'll know, when it happens because, the people in my life are a reflection of that.

The things I get to do and the things I've chosen to do fulfill me. So if I've been able to actualize that. I can pick an image, I can pick a line. And maybe I don't have to pick, there's five lines representing one line. like a lot of paintings are just like, I'm not picking, I'm just gonna do everything and do it all, and then edit into something that makes the most sense.

Ajay Kurian: Let's have one more, but I have a quick question based off of that. Rick Rubin was interviewing James Blake. And James Blake was talking about that he's not good with melody and that he feels weak in melody. And that already was like a funny thing for me. I was like, really? And he was like, I could take something that I thought worked pretty well and then just start looping it and then building it and transforming it. It was almost like he took a weakness, what he saw as a weakness and made it a strength. He was like, I'm never gonna write like a pop melody like Miley Cyrus.

Janiva Ellis: Like a collage. I think some people are collagers, some people are inventors. I think he's got a lot of influences doing a lot of work for him. And I think that he's maybe a curator. I haven't listened to a ton of his music, so I don't wanna flatten the thing, but you know how there are good curators. I'm like, you're really good at that. You're good at looking at stuff. You're a strong connoisseur. Some connoisseurs make things and some people are riffing and some people are channeling, some people are inventing, some people are contorting, some people are crashing all the way down so that they can pick one thing up and make it something. And some people are really good at research. Some people have 60 tabs open and they look at every tab and they, absorb it and they use it and they take it. Some people have 60 tabs open and for years, and then take one thing, different approaches. I'd say James Blake looks, seems like a person who has 60 tabs. He looks at every single tab and he uses and extracts all the stuff.

Ajay Kurian: How many tabs do you have?

Janiva Ellis: A million. The tap culture is so intense, but there was an impulse to follow one thing, and then maybe a few of those things will be used. I'm not trying to create a comparison between me and James Blake, but I think there are different approaches that produce different types of work, and there's a different catharsis to be had in that output. Like thinking about Rauschenberg versus Winton, I just saw the Winton show, incredible. Such a relief. Thinking about that work, thinking about Rauschenberg, it's a different approach to assembling things from other things and they have their different values.

Audience Member: Hey, Janiva. I love hearing you speak. I really feel a lot of the things that you're saying with disillusionment at the immediate recuperation of identity politics into capitalism in the art world. That's just an aside, but I had a technical question. I liked what Ajay said about palimpsest and layers of drawing, and mark-making superimposed on top of each other.

That's something I see a lot of in your earlier work, decision making about how to draw borders and lines. Like you make decisions about where to end something with a graphic area of color. And now the new work is like extremely exciting. It still has that drawing trace, but it's expanded and maybe less based on referential images. So I'm curious like where you're at with, being beholden to reference images and also how you've changed your decision making around, where to merge or diffuse or make clear elements of drawing.

Janiva Ellis: That's a painter right there, that's a painter's question. A fab painter, skilled, talented.

I decided to take my time. I think that's the choice. I think early work was speed and I have so many ideas and I don't know how to keep up with them. Just gonna do it. It's done. It was a lot of shorthand for ideas because I was like, this is my shot.

I don't know if I'm gonna do this again and I don't know what time I have, I don't know if I'll have the money to do this again. I don't know if I'll have the support. I don't know how long this will last. I'm just doing it now.

I hadn't fully finished this question where I had taken about four and a half years after school where I wasn't painting for a number of varied reasons.I had such a kind of truncated relationship to when I would start and then it would be clunky. But there was just a lot of self-doubt, a lack of funds, a lack of space, and a landscape that didn't seem like I even cared about. Coming into it again, I was renewed with a sense of enthusiasm that made me paint quickly. That was around the time that the Kerry James Marshall Show, had happened and was touring the country Mastery. There was a Robert Cole Scott show, there was just these shows that I was like, oh my gosh, I don't have time, I gotta do this. We don't have time and so I was moving really quickly.

I think the difference now is I'm moving more slowly. I am sitting with things, I'm taking a step back, I'm taking naps, and then I go back in and I'm like, okay, I'm gonna paint over that. I don't need that and I'm gonna go back in with a more measured hand.

I think there was a different type of editing that was happening at that time where I was like, paint black over it. Paint another face, paint this, paint that. But there was a crudeness that came from the speed. And I think there was a lack of technical concern. I did care of course, about communicating a competency around painting and a knowledgeability around the history of image making.

But precision wasn't the priority. I was like, there's a lot of ways to communicate competency, and precision isn't the one I'm focused on right now. Now I think in lieu of prioritizing the conversations I was wanting to have in that work, because I'm communicating them in what I'm very firmly planted in as an institutional context.

And things are morphing, if I wanna keep making art, I have to find joy in it. That's through learning and that's through getting better. So I'm gonna take my time, and not as fixated on the reveal of violence and like the feeling of like black people, are you out there?

I wanna connect to you. This happens, I'm not crazy, that’s weird, right? That really formed my personality at the time where I was just like, are you guys there? Is this happening? And now I'm not in that place. I'm like, I have my fucking people around me. I feel cute, I feel fab.

I'm sipping wine and, this is so fun. Still feeling crisis, but like finding catharsis and like learning about forms and then getting to sprinkle ideas on top of that form and that understanding of what makes forms like deep and resonant.

Ajay Kurian: All right, last question.

Audience Member: Hello. I somehow found myself living in Somerville, Massachusetts, and I saw a flyer for your paintings at the Carpenter Center, and I was like, in my way, Massachusetts is my Hawaii. And I was like, oh, this will be a chance to meet people so I went on Friday but the opening was on a Thursday. But I had so much time to sit with your work and I didn't realize I had met you before, but I was like, I had served you at a restaurant once, that's crazy.

Janiva Ellis: This relationship between working in the service industry and meeting people.

Audience Member: It's New York, I feel like. So one thing that I really think about when I see your paintings is I'm someone who loves to be like under the covers and turn a flashlight on. I feel like your paintings are inside when we're outside. And I'm just curious about the architecture of your dreams and memories and like how you reflect on them?

Janiva Ellis: Wow. I will say that, when I first left Hawaii, my dreams were really vivid and the recall I had with my internal inventiveness was spill over. And being in New York for a long time and turning this catharsis into a profession, has created certain gaps, like in in the freedom of my subconscious making contact with my conscious feels cloudier and concerned with things I don't care about in the emotional sense, and the fulfillment sense.

So I had this really vivid dream the other day, a very art world dream where it was very like conspiratorial dream about how I was being attacked and all these things, but it inspired me 'cause I hadn't made contact with a vivid dream in a while. The vivid dreams happen and when I go back to Hawaii or when I'm not in the city, it is a little associating freedom, saying yes to impulse, like all of those things.

Ajay Kurian: I can't thank you enough.

Janiva Ellis: Thank you, honestly. Thank y'all. I really appreciate you guys coming. Ajay and I have been talking about doing this for a while and I'm glad that it could come together. This felt very cozy. I was nervous and this felt very normal and really nice. So thank you.

Ajay Kurian: It's really my pleasure, thank you so much. Thank you all for keeping the energy and again, let's give it up for Janiva.

Share this post