She paints memory, sensation, and the space between languages. Candida Alvarez on intuition, inheritance, and color as a vessel for care.

Candida Alvarez is a painter whose work explores personal and cultural memory through abstraction, vivid color, and layered visual language. She draws from Caribbean diasporic experience, family history, and city life to build complex surfaces that hold both clarity and mystery. Her work has been shown at the Whitney Museum, MoMA PS1, and the Chicago Cultural Center, with recent major exhibitions at GRAY Gallery, Real Monsters in Bold Colors: Bob Thompson and Candida Alvarez, and her first large-scale museum survey, Candida Alvarez: Circle, Point, Hoop, at El Museo del Barrio.

She explains:

Growing up bilingual and between cultures, and how that shaped her approach to painting and storytelling

Why color, surface, and rhythm carry emotion, memory, and political charge

Painting for resonance instead of clarity, and letting intuition lead the process

Using abstraction to hold grief, joy, labor, and inheritance in the same frame

Returning to domestic and familial spaces as a way to build intimate visual worlds

How risk, repetition, and instinct guide her through not knowing what the painting wants

The connection between care, culture, and making art that listens as much as it speaks

(00:00) Learning to See as a Bilingual Kid

(10:18) Color as Voice and Resistance

(20:47) Working Through Grief and Reverence

(31:02) Abstraction as Intimacy

(42:11) Teaching, Listening, and Long-Term Practice

(52:36) Making Shows that Listen Back

(01:04:10) Holding Presence in a Fast World

(01:14:32) Refusing to Be Defined by Trends

(01:24:45) Language, Memory, and the Visual Archive

(01:34:56) Painting as a Form of Freedom

Follow Candida:

Web: https://www.candidaalvarez.com/

Instagram: @candida_alvarez_studio

Follow GRAY Gallery:

Learn more about Candida Alvarez’s exhibition, Real Monsters in Bold Colors: Bob Thompson and Candida Alvarez, at GRAY Gallery NY here.

Web: https://www.richardgraygallery.com/

Instagram: @richardgraygallery

Follow El Museo del Barrio:

Learn more about Candida Alvarez’s first large-scale museum survey, Candida Alvarez: Circle, Point, Hoop, at El Museo del Barrio. here.

Web: https://www.elmuseo.org/exhibition/candida-alvarez-circle-point-hoop/

Instagram: @elmuseo

Full Transcript

Ajay Kurian: “Dame un numero” which means “give me a number”, Candida’s mother would tell her. She intuitively knew that her mother meant a number from one to 26 in accordance with the alphabet. Selecting a number meant selecting a letter, and the letter would be her mother's compass to find out who is trying to contact her from beyond this realm.

I love this story. It so quickly highlights how Candida is in this world and others, and the plays she sees in living. I met Candida Alvarez in 2023 at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, a residency program in Maine where we both were faculty that year. I got to see her process as an educator and an artist, and at the root of both is a profound level of observation and responsiveness.

It's always fun to talk to Candida. But when you ask her questions about painting and her practice, there's a different level of focus than that emerges. One where I notice myself hanging onto her every word. There were many times when it felt like she was tapped into something past this world, and her words were like a tunnel to that elsewhere.

In those moments, it's best to shut up and listen. So I went back and listened to the talk that she gave at Skowhegan. When she finished, she was going like a mile a minute, and then she finally finishes and she quietly stops and says, thank you. And in what became typical fashion of the end of a Skowhegan talk, the room erupted with both applause and foot stomps more like a stadium than an art talk.

But then a hush came over the room as she opened it up to questions. You could even hear it in the recording, and it’s something that I can't really explain. You could hear the spotlight on her, the concentration on what she was about to say. What I wanna say is that Candida has a bit of magic about her, and after a long time, New York gets to feel it.

So with that, I'm just gonna list off some accolades of yours. Alvarez has participated in residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting, Studio Museum in Harlem, the Luma Foundation, among others. Recent awards include the Trellis Art Fund Award, the Latinx Artist Fellowship Award, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award.

Her work is included in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Denver Art Museum, the Studio Museum of Harlem, and the Perez Art Museum in Miami, among many others. Everybody give it up for Candida Alvarez!

Candida Alvarez: Thank you. That was so beautiful.

Ajay Kurian: How are you?

Candida Alvarez: I'm not sure.

Ajay Kurian: Let's start with a number. I feel like the number 2 is the one that always comes up for you.

Candida Alvarez: Well, I was born the second day of the second month and I'm the second child. So I guess you could say 2 does circle around me. But if I asked you, what would you say?

Ajay Kurian: I would say 23.

Candida Alvarez: 23.

Candida Alvarez: T? No, UVWX.

Ajay Kurian: Anybody?

Candida Alvarez: X?

Ajay Kurian: X?

Candida Alvarez: No, no. There's 20. It's Z. That's a big one.

Ajay Kurian: Z, Y,, T, V, W, X, Y, Z. So Z, Y, X. Yeah. It's 20. It's X.

Candida Alvarez: Yeah. Okay. X.

Ajay Kurian: What do we do with X?

Candida Alvarez: Malcolm X, Latin X.

Ajay Kurian: Oh shit.

Candida Alvarez: X-ray, Extra, Xavier — X is a hard one, but not really. X is like multiplication, right? X is the thing you don't wanna get when you go up to show your math teacher the answer to the problem and she goes, X it means wrong.

Ajay Kurian: I feel like I guessed wrong.

Candida Alvarez: No, you did what you had to do. You gave me a challenge because that's a long way down the list. If my mother asked me, I would say four. I never played that all the way at the end.

Ajay Kurian: But you played that game enough that you knew like, don't do twenties. That's X. I'm new to this game.

Candida Alvarez: It's all right. Ask me another question.

Ajay Kurian: We're looking at your retrospective here at El Museo del Barrio and it's called ‘Circle, Point, Loop’. Here are some install shots of works that are called View from John Street.

Candida Alvarez: Yeah, those charcoal drawings were from John Street, Brooklyn where I had a studio and that building's still there and there are still artist studios there. I was up on the second floor and it was a great space. It was one of my first spaces in New York. It was very dangerous. I remember one of my father's friends gave me a really old car to drive. I could see the plant and I could see the water beyond. I had a residency in Germany that was through a program in Philadelphia — creative artist network, I believe. And I learned about it through a fellow artist in residence, Charles Burwell, who was from Philadelphia. It was an opportunity for an artist to go away for a month and they chose the city. So I went to Cologne.

Ajay Kurian: Wow.

Candida Alvarez: Right. That's what I said. And I spent a lot of time at the Dome Cathedral. I was fascinated by it structurally and what it meant for the city.

But also there was this above and below. So, below was the crypt of the church and it was beautiful. It was a beautiful space with little light bulbs and just sort of a very special place to chill out in after a big day of traveling around. The church was filled with a lot of art and stained glass. I met so many wonderful artists there. And they actually put together a catalog for me and they curated a show, and those drawings were a part of it that I actually did in John Street. So I came back with a lot of beer coasters — the circular forms, which I was fascinated by. And I just wanted to do charcoal drawings, which I had never really done, but I think it was the dust, and the dusty feeling.

I just used charcoal and got to work. You can see the circular pattern came from one of those beer coasters, and tape was used to get some of those rectangular shapes. I used a razor blade to get these kind of whitish, almost dashed lines through the paper. I got totally engaged with them and after I did them, I didn't do any more.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, I mean I've never seen a charcoal drawing from you since. It was really part of going to that show and like walking through the museum.

I've known you for a couple years now and I've seen the work and I understand that color plays such a huge role in how you think about life. So it was surprising to see charcoal drawings and just the breadth of the work. There's so many different projects, there was so many different ways of working. Did this feel foundational? Because you talk about drawing a lot as really the root of what you do.

Candida Alvarez: Well, I think there's something beautiful about blackness and black is a color. I mean, people don't often think of black and white as color, which I find kind of interesting. But it's really a beautiful way to see deeply.

I love charting space using black and gray tones. There's something about commanding space with a very little tools, right? The stick of charcoal is kind of beautiful. That one thing that can create all this magic, I find really beautiful. I just didn't like the dustiness so much, you know? Charcoal is hard to pin down. I love the highlighting, the light and dark, and I also like taking pictures. You know, I had a camera for a long time and my first tool was a camera.

Ajay Kurian: They almost feel like abstract photographs.

Candida Alvarez: Yeah. I love black and white photography. I fell in love with it. I used to love Roy Decarava’s work, where he went from pitch black to white. And Harry Callahan.

Ajay Kurian: That's when you can see that black and white are colors.

Candida Alvarez: There was something poignant and very stark, and at the same time, the gray tones allowed for a time interval to be introduced into the compositions. When you just have black and white, your eyes move really fast. But when it's gray, your eye moves. Like it's on a tripod and it could be moved. It's more like when you're making films. I love classical film — vintage black and white films.

Ajay Kurian: Did you grow up watching a lot of movies?

Candida Alvarez: I think television was mostly black and white for a long time. But yeah, I did. Not a lot, but enough to keep me at the edge of my seat. I think to have a camera and to be suspended in time, to have Polaroids, that was magical to me. I really thought I was gonna do more work with a camera. But I still do work with a camera, because I take a lot of pictures for my own documentation. I just don't show them.

Ajay Kurian: Why don't you show them?

Candida Alvarez: Cause I don't need to. I just use them.

Ajay Kurian: So they get used for compositions? Or how you think about the work?

Candida Alvarez: Well, I love capturing details of my daily life.

Ajay Kurian: So this is in the eighties and then by the nineties, that's when you apply to Yale, get in and go there. I think there are consistencies, but also there's some really major things happening.

Candida Alvarez: There was more change. It was less photography and more about the body interacting. I came up with a way to identify a sort of a dimension to this idea of intentionality, which is the name of this case study with Mel Bochner. Of course, that was his big question to us all the time. What is your intention?

That was a word that I held onto and I was trying to define it for myself. I wanted to have a formal way to define that. That was my curiosity, and so I wanted to move. When I got into Yale I was doing those multiple panels. They were really colorful. This all happened at Yale because I was trying to unpack something that was significant. I was really trying to mine my life experiences. These kind of ways of being in the world. Like the ways I listened, let's say in my family, the way I heard my mother, the way I paid attention, the way my father taught us a game of boxes, right? I love the systematic nature of that. I just like threading through the unexpected and I wanted to sort of use this language and invent a language that came outta something really familiar.

Ajay Kurian: Mm-hmm.

Candida Alvarez: But yet it was very conceptual. It like all of a sudden got elevated to something else. And so I love the retranslation of something unexpected. The mystery of making for me is very exciting, but the context is also really important — how it begins. And what are the questions and why is that so important? Well, it was a way to identify, right? Who am I as the artist? Why is it that what I was making was boring? To me, it was becoming boring. Because familiarity gets boring to me.

Ajay Kurian: Could you see yourself in these? So we're looking at almost like a wavy grid of nails that have kind of looped wire around them and rubber bands.

Candida Alvarez: But I was drawing with nails, pencils, and rubber bands because I was reconstructing the language. I was naming, I was using, it was kind of using the alphabet. It was a way to get back to a word or to a beginning point, like the word intention or the word convention I was using. I was kind of mimicking Mel in a way, but in my own little weirdness I was able to respond. So I was responding.

Ajay Kurian: And did he see it as a response?

Candida Alvarez: I think he was intrigued. I didn't reveal all my mysteries, you know, I just kind of went for it.

Ajay Kurian: I don't think you ever do.

Candida Alvarez: No, you can't. You kind of just do what you need to do. You don't have to over explain anything.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, then it dies a little.

Candida Alvarez: I like to keep some mystery.

Ajay Kurian: I feel like there's a lot of systems early on. I mean, there's always systems, there's always patterns and finding ways to make a composition based on kind of chance operations too. Like this one, tossing pennies literally happens from tossing pennies.

Candida Alvarez: Exactly. But that also came at the beginning point. Goes really early back to my father who tossed pennies in the air for good luck. So as this inquisitive child, I'm more mesmerized by the fact that the penny is tracking a pathway. There's something about the penny being flung that was more interesting to me than the penny landing. But the landing was the luck. Somehow it's like what held the space. It kind of held the space in a way that that's what my father's desire was. So was that what he wanted? It was weird. What can I say? But I noticed it and I wanted to use it.

This was one of the first pieces I did when I got to Yale and it was an empty studio and I just looked around the room and collected things. Those were all free for taking, 'cause they were just pieces laying around. So I just used them and I love the way that I felt free enough to organize them together.

Because that was new for me. And then I had my son in 1991 and I was there in 1995. So that's my little son's hand, Ramon. He was in the picture too, so I made that little thing.

Ajay Kurian: Oh, right here?

Candida Alvarez: Yeah. That's my son's hand. So my son was there with me too. So what happened was I had those pieces of wood paneling and then I just started tossing the pennies into them. Wherever they landed, I just traced them or I glued them down. Then I had these little pathways and I really was very intrigued about that. Like how to mark territory and how to create a space that was coming out of something intentional in a way. And also memory. So it was like solving a puzzle that I felt I had to create for myself as the artist.

Ajay Kurian: You know, I feel like the word abstraction gets used a lot, and a lot of times people mean different things when they say it. And I love how much you bristle at the word abstraction because it bothers me too. I think people use it too freely and I'm using your words here where it's like we're abstracting all the time. When you think about your practice, what is a better word to describe what it is that you do?

Candida Alvarez: I paint. I draw.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah. Okay. I'll take that.

Candida Alvarez: What do I think? Like we were talking about Vernon Reid, I mean, I love Vernon Reed, and when he came out with that album Living Color, I was just blown away. I was blown away. 'cause he collaborated with Greg Tate. They were artists who worked with words. The lyrics are so incredible and powerful. I took that to represent what I do, you know, living color. I could never forget that. So for me, when I talk about painting — I love painting because I can use color and color is living to me and that means that it can change. It changes depending on where you situate that painting.

What kind of light is on that painting? I love that. I love that it's alive and I think that's really what I like to do. I like to wrestle with color. There's something about that engagement that never ends. It's a conversation that's continuous. And I just love it.

Ajay Kurian: I feel like that shift into color, like, I'm actually curious because to me, I've known your work when color was always there. It was like foregone occlusion. But in these works, like for instance in extension, you know, there's definitely color. How do you conceptualize a shift from a piece like extension to what we're gonna see in a bit?

Candida Alvarez: Well, because these are all stepping stones. They’re all steps towards something and that's the mystery of making or being the artist, right? I mean, I only make these pieces 'cause I wanna try to understand something and I'm not really sure what that is yet. But it's the mystery of wanting to discover something that keeps me going.

Ajay Kurian: This feels like a portal to me. There's a lot of mysterious works, but this one in particular really does stand out.

Candida Alvarez: That's convention extension. Well, I was responding, because we had to read Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence.

Ajay Kurian: Was he teaching there at the time?

Candida Alvarez: No, this was Mel's class. I think for me, I was talking to myself, so I wanted to extend myself like a clock. I wanted to see myself like the Vitruvian man. I was like, I could be a star. I could be a man extending like a clock.

Ajay Kurian: Candida’s talking about DaVinci's Vitruvian man.

Candida Alvarez: Very famous. I’m sort of intrigued by history, and history that maybe people don't think I should be a part of, you know what I mean? By chance you bump into things or you're reminded of things. It's like you ask me a question and all of a sudden you take me on a tangent or something. And I might have not been thinking about that as a portal, but all of a sudden I can connect something that I was thinking about.

I think it's having the courage to just do whatever the hell you wanna do. And we just get so locked into other people's expectations. When we're young, we're students, we hang on to every word and we try to be the best that we could be. But sometimes you just forget yourself in that equation, right? Because you're trying to be something that you think you should be as opposed to being what you really are. And so I think learning and unlearning is a part of it all.

Ajay Kurian: Did you always have that courage?

Candida Alvarez: Probably not, no. But I failed at trying to be perfect. I like to practice my penmanship, and I loved the practice of calligraphy. I tried to be good at math and I was terrible, but I tried my best with trigonometry and all of that. I didn't know that I was an artist or I wanted to be an artist because that wasn't something that was in my early learning. But the daily news had this little picture that you could color. To me it was like little paint by number, like a wall thing. I used to love to do that, and I used to love working with collograph.

Ajay Kurian: What was that?

Candida Alvarez: That game where you peel the plastic and it was all these shapes. I was always drawn to something that I could participate in. But I never knew that this was my path.

Ajay Kurian: But then you go to Yale, I mean of course it was years later. First you went to Fordham and that’s when you really started to feel it.

Candida Alvarez: That's where I took art classes. And I wanted to carry that big black portfolio. I was fascinated by that big black. Then I got lucky. I took a class with Susan Crowell and Jack Whitten. Paul Brock was teaching history and he was married to Miriam Schapiro. So I got lucky. It was the seventies. Somebody like Jack, I didn't know who he was.

I didn't know that he was such a well-known artist, but I took his class and he was very encouraging. I didn't have a lot of supplies and I didn't know how to stretch a painting. But I used to go to Pearl Paint and buy my stretch canvases.

Towards the end when I was graduating, Jack looked at me and said to me, you know, if you continue to make those pieces really big, you can actually win awards. I was thinking, is he really talking to me? So I was kind of shocked, but what happened was, at that moment, he was paying attention and he noticed the seeds that I had. He acknowledged them and made me aware of them. And that gave me pause and gave me something to really think about. And that gave me a lot of courage.

Ajay Kurian: That's beautiful.

Candida Alvarez: Right. But he actually said, you should apply to Cooper Union. So I asked for the application. It was about, I don't know how many pages, but I looked at it and kept turning the pages, and I was like, I can't handle this. But fast forward how many years? And then I'm teaching at Cooper Union.

Ajay Kurian: Wow. Right.

Candida Alvarez: And I'm like, I guess I did have to come to Cooper Union and to make my move back to New York. I mean, here I am again.

Ajay Kurian: You've taught for so long. You were at the SAIC in Chicago for…

Candida Alvarez: 20 years.

Ajay Kurian: When you started, it was in the late nineties, right?

Candida Alvarez: Yes, 1998.

Ajay Kurian: Did you feel ready to be a teacher then? I guess Ramon was probably what, seven, eight?

Candida Alvarez: So I went to Fordham, but didn't go right to art school. I went and stayed at El Museo del Barrio, that had free classes and workshops, so it was a little easier to handle because there was no expectation. So Bill was teaching there who was a phenomenal printmaker, actually he was a professor at Pratt and he came to work there part-time.

While I was there, I started looking at catalogs. I had one of Vermeer Bhutan and I fell in love with those black and white photo montages. I think that there is something about that dismantling and gathering of something familiar that's interesting to me. So then from there, I did a little curatorial engagement with pre-Columbian art. I was studying pre-Columbian art.

So we had this book and I was fascinated by the little statues that they were collecting — the wooden sculptures. Then from there, I learned about the Cedar Artist Project, which happened in the late seventies or early eighties. That was another really amazing and very robust community of artists that came together. It was the first time that the city of New York actually paid artists to do their work. And I got lucky. I was part of the first group and stayed there, and that's where everything happened.

So I started to feel more confident in being the artist. I was probably the youngest one in that program. They had photographers, they had painters and, and I was kind of in the writer's section. For some reason they had groups. I was with the poets, but lucky me in a way 'cause it was like Bob Holman and Pedro Pietri. But we all met once a week to get paychecks. It was fantastic to feel the energy of being an artist in New York and to be able to do what you do and get paid for it. It was just unbelievable.

And then I stayed in New York, got married, had a son, and my partner wanted to go to Yale to get his master's degree in photography. So we went as a family. He graduated and then I was like, well, I think it's my turn. So that's how it happened. That's how it landed in Yale. There was a market crash. It was a good time to leave the city. Artists weren't making any money, but a lot of us were going back to school to get our degrees so we could make more money.

Ajay Kurian: Right. Teaching classes. You know, today it’s like, on the one side of things, you can maybe be a mega star and make all this money as an artist, and then there's the sense that nobody's making any money and it really isn't a great career path for any reason at all. But I feel like that program gives you this sense early on that like oh, I can do this, I can make a living off of this. It just seems like a really specific thing that you might've just…

Candida Alvarez: Lucky.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah.

Candida Alvarez: It was three years for us and we had a really cheap apartment, which we lost and it makes me sad thinking about it ’cause I used to have my studio right in the front.

But anyway, we lived in Connecticut and I had found a beautiful studio at Rector Square, which is not too far from the school — our son had just started school.

Ajay Kurian: In my head, I've heard this from many female artists that either are thinking about children or have children, that they've heard from gallerists that if you have kids, it's gonna damage your career if you do this. There's so many shitty things that female artists get told. But you just jumped in.

Candida Alvarez: It just kind of happened. But I want to say something — Bob Holman was married to Elizabeth Muray, so I got to meet Elizabeth Murray and became friends with her because of Bob, who I met at the CETA Artist Project. She had at least three kids. It was never an issue.

And Hettie Jones who was the mother of Kellie Jones was also a dear friend. And I'm trying to remember how I met Kellie, but it must have been the Studio Museum in Harlem, because I was also an artist in residence in ‘85. And so there were shows at the Jamaica Art Center that Kellie curated. We were all beginning our careers. We were all in the beginning.

Ajay Kurian: Did you know Daisy Elizabeth's little girl or did you ever meet her?

Candida Alvarez: I didn't really know them that well. But Elizabeth was a great mother and she was a fantastic artist. She wrote the essay for the first show that I had at June Kelly Gallery.

Ajay Kurian: No kidding.

Candida Alvarez: And that was her first ever essay for an artist.

Ajay Kurian: Wow.

Candida Alvarez: It was very beautiful.

Ajay Kurian: I feel bad that I haven't seen that, I need to get access to it.

Candida Alvarez: It's somewhere in my archives.

But so, I don't know why certain things happen. You know, they just happen and you notice and you just feel like your life keeps moving, right? But I had no idea that this is the person that I was becoming. I just trusted something. I mean, you have to have courage. You have to do things that may be scary, like move out of the city or marry somebody you love or have a child or take up classes. I mean, it just kind of started and it just wouldn't stop. I couldn't let it stop, no matter what. And I wasn't selling a lot, you know, I just kept doing it.

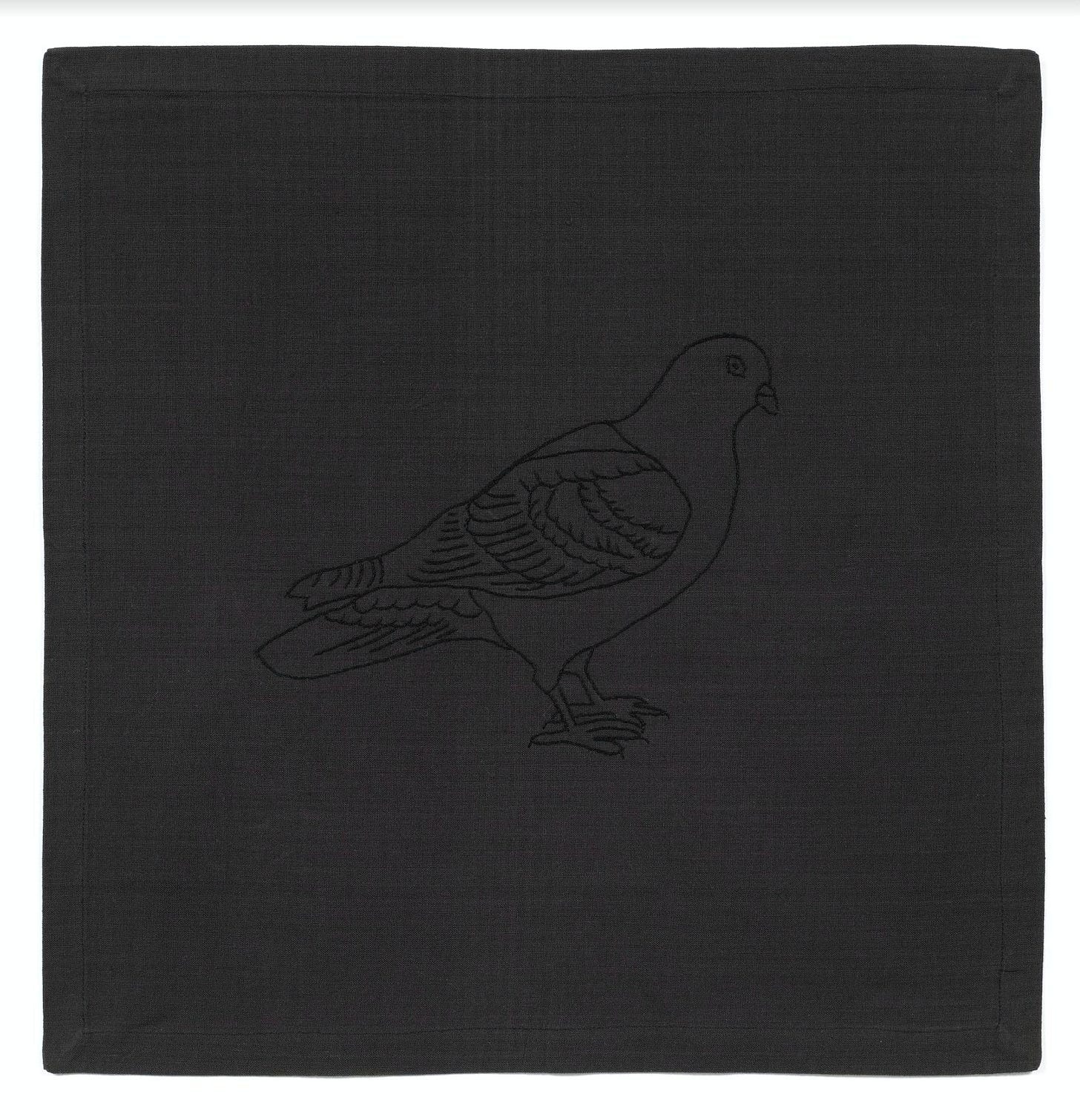

Ajay Kurian: What did you trust and what brought you to all black embroidered images? Seeing this at the Museo threw me completely, like for the Skowehegan people that are in the room, it's crazy. You go into a room and it's all black and it's fucking wild. It was beautiful. There was so much weight there. And then there's a video of your mother and she's preparing food and she's very serious too. It was a really powerful room. I have so many questions.

Candida Alvarez: Well, black and white drawings, right? So this is going into a very deep, dark space, but there's a lot of tenderness in that space. The sewing, which I did by hand.

Ajay Kurian: It is very tender.

Candida Alvarez: The light captures it in such a way, and I love the whole idea of thinking that the viewer thinks there's nothing there, but then you have to get really close and then you notice something.

I started to work with dinner napkins because they were soft and easy and my son was little and I couldn't get to the studio. So I needed to work on something that I could take with me and do it on the bed, or the chair, wherever I could watch my kid running around. So I would just take them and, and make these images.

My mother collected and was given a lot of porcelains, and she had a lot of them in Puerto Rico at this time. My parents were living in Puerto Rico and we lived in Connecticut. Then we came back and I had a studio, and these were done in Chicago.

So I was doing these small drawings and it was really interesting. At some point I remember seeing this small little painting by Francisco, a Puerto Rican painter. I went to Puerto Rico just before, like in the seventies for the first time.

I went and I met Lorenzo Homar, who's an artist I really admired. Puerto Rico has these amazing artists who worked that I noticed with printmaking. I didn't really know a lot of the visual artists, but from Fordham University at Lincoln Center, I met somebody there who knew this artist. And so that's how I got to the studio for the first time and I was so nervous. I remember Harley talking to him, but he told me to read all the books in the Social History of Arts.

Ajay Kurian: Oh wow.

Candida Alvarez: I wanted to go to Paris, and I think it was during the CETA Project. When I had a little bit of money, I took myself to Paris because I wanted to see the work of Francisco firsthand. I saw that work in the eighties because there was a show that El Museo del Barrio was putting together with the Met and it showed a lot of work from Puerto Rico. This was one of my favorite paintings and I wanted to paint like that. When I saw that, I was like, I wanna paint big.

Ajay Kurian: From 1893. The weight.

Candida Alvarez: 1893. So he did a piece that's much smaller and it was a portrait of a meal order. He was drinking tea at a table. And right next to him is like maybe his housemaid and she has this big dress on her lap. This black material and she sewing. So it was years later after I made my black drawings that I remember seeing that painting. And I was like, did that really affect me? It was so wild. I was like, oh my God, I became that housemate painting.

That painting was so beautiful. It was facing the Mona Lisa, that little painting. So that was an amazing moment that I'll never forget.

Ajay Kurian: Wow. I would've never known that whole backstory. I mean, the works are beautiful and they're moving on their own.

Candida Alvarez: I don't think I've talked about it, at least not in a long time.

Ajay Kurian: That's incredible.

Candida Alvarez: Well, that's why conversations are interesting, right?

Ajay Kurian: Is that why they're called lap drawings? 'Cause you were literally sewing…

Candida Alvarez: On my lap.

Ajay Kurian: So then they got bigger, right?

Candida Alvarez: So the big ones, I still did them on my lap, but they were bigger.

Ajay Kurian: They're huge.

Candida Alvarez: Yeah, they're really big

Ajay Kurian: I'm gonna skip ahead a little bit. I wanna go to the air paintings. So 2017 was a really consequential year for you, for a whole number of reasons. There were amazing things that happened and not so amazing things that happened, and it feels like the air paintings kind of became a way to process the ups and downs.

Candida Alvarez: Well, in 2017 I had a really big show at the cultural center that was curated by Terry Meyers, who was one of my colleagues at the School of the Art Institute Chicago. It was a very important show for me. So after it closed, my father died. He was in Puerto Rico and then about three months later I was there with my mother and my sister went to stay with my mother 'cause she was grieving and my mother has never lived alone.

I mean, it's been years. But when I left and my sister was there, Hurricane Maria came. So it was devastating because we couldn't find our people, right? We were all searching on Facebook and trying to connect with people who were there and the cell phones weren't working.

There were weeks and weeks where we were just frantic and not really knowing the state of things. So I was in Chicago trying to keep sane. Because my mother and sister were there and we couldn't find them. We couldn't hear from them. But there was something that said, I'm sure they're okay.

Just before that happened, I had a commission that was sort of this digitized mural printed on mesh which was used for banners. Chicago has a lot of mesh. This was for under the Wacker Bridge. The engineers had to construct the weave in such a way, so the bridge wouldn't come down. So this idea of air was really important to the design of the material, and I was fascinated by that. It's like a canvas, except that this was outside. But there's that little window of air, and I kept thinking about that.

Ajay Kurian: It makes me think of you being fascinated with launching the penny.

Candida Alvarez: Exactly. There’s something about something else that happens, inside and outside of material. Or inside or outside of functionality, that gets to something that is mysterious, like a wish, right?

So I had to produce this piece. It was very big. It was one of my largest commissions outside. It was like maybe 200 feet across and 70 feet high, multiple panels. We had a proofing process, and so these pieces came from that proofing process. They were the excess and the stuff that wasn't used. So I just asked for them. I wanted to take them and I just rolled them up and took them to the studio never thinking I would use them.

It was during this time period when we couldn't figure out where my mom or her sister were or how they were doing. It was a very restless time. I decided to unroll them and just do something kind of different. And so I started pouring pain and squishing pain and stepping all over it and just doing something else. That's how these came to life. That's why they're called air paintings.

But also the framing for them took a while to get to. I didn't know what to do with them 'cause I never thought I would show them. I was just making them. And then I thought, wow, two sided paintings.

Ajay Kurian: Is it sandwiched between the aluminum at the top?

Candida Alvarez: Yeah. There's a really beautiful way in which they get inserted with a wooden dowel. I'm very happy with them. And so sometimes I refer to them as paintings with little feet, but it was the first time I've ever had a show and I wanna say thank you to Monique Meloche because she was really the only person that wanted to show them. So I was grateful to her for showing them and taking them on. Because I've never shown anything like that. I've never had a show where I didn't use the walls.

Ajay Kurian: Right. It was all in space.

Candida Alvarez: But I love the idea of working with these, like a kaleidoscope. Eventually I'll do more of these because I still have a plan for them.

Ajay Kurian: They're really great. There was a quote that you said around the time of producing these, Mother Earth is dealing with all of this abuse, and it's in overdrive right now. So people are scared. When the ground doesn't stop rumbling, you don't recognize your home turf. You become lost as the walls crumble. Overall, there's lots of tenacity and creativity. Overcoming fear is just part of who we are as human beings. We have to stand up for something. We have to love something. Death and life are so close together.

And when we suffer trauma, we're pushed in different ways to remember that there are ways in which you can find and be reminded about what is right and what is wrong. And this, I think, is kind of key. Still be the individual in the room without losing our commitment to community. I thought that was really moving just in terms of being able to center yourself, but also realizing it's not just you going through something and it's not atomized.

We can hold space for ourselves while within the community. And it, when you say that there was nothing on the walls, they're all taking up space together. There was a community of works.

Candida Alvarez: Community has always been a very important word to me. It's always been important. I can never live life without it.

To think you're all by yourself here is kind of, I mean, you are on some level, but we all need each other on another level, right? I mean, love is so important.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah. Right?

Candida Alvarez: You need the seeds to grow from and with.

I mean, to take the courage you have to fall in love with something. Or to dare yourself to do something, you know? Or like why pick up a brush? You know, why pick up a pen? What makes us do those things? Outside of an assignment.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, the assignments end.

Candida Alvarez: But you know, when we were kids, we would take rubber bands and we would nod 'em together and skip rope. They called it Chinese jump rope. Or you had a long piece of rope and then we did double dutch. So think about that, right? The way we were being creative since we were really young.

Ajay Kurian: This work is called I'm Okay or I'm Good. And it finds its way into a much larger landscape and it makes me think, again, of the individual in the community. Somebody shouting out, I'm good! But in this landscape of all these other things happening and potentially a lot of destruction happening as well.

That phrase became really powerful for a lot of people because like first it was for this particular work and then it was for the triennial.

Candida Alvarez: It became Estamos — being.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, exactly.

Candida Alvarez: The story came from listening to all the interviews with the Puerto Ricans that they were trying to find up in the mountains. They would say, well, how are you? Well, what am I gonna say? I'm alive, I can talk to you. But it was kind of a way to sort of hold the space, so you wouldn't ask me anything else, or I might start tearing or something, you know? It was a way to hold space. To hold oneself together. It's like a quiet period. I need time to reflect and I can't say anything else.

It's kind of more cynical than not. But I was trying to be okay too and I was trying to do what I loved and it felt good. I could disappear for a while.

Ajay Kurian: I like that you say that it was kind of cynical because it became this banner of we're okay, we're fine. But you're hiding a lot of pain. It's just like, just shut the fuck up and leave me alone.

Candida Alvarez: Exactly.

Ajay Kurian: There's two sides to that. And it's nice to hear it from you, because you feel it too. There's something protective about it. Even though there's air that's going through it, even the way that it's in the painting formally speaking, it's there, but it's not, it's not welcoming you. It's not bringing you in. It just happens to be there.

Candida Alvarez: Well, I remember writing that too. I felt like it was almost like a little text bubble, like a pop.

Ajay Kurian: You have a show at Richard Gray Gallery right now with a person who I think has been very influential on generations of artists, but of course for you as well, Bob Thompson.

Candida Alvarez: That was the first piece I fell in love with at the Art Institute of Chicago when I started teaching.

Ajay Kurian: This is called Equestrienne.

Candida Alvarez: From the Tang Dynasty. And I did a whole series of paintings using that figure.

Ajay Kurian: It was called flower of the Horse.

Candida Alvarez: I was very interested in describing a beginning and ending point. I was tracking my tenure and my emeritus status, and I was leaving teaching. So I wanted to do these pieces that were paintings that really reflected this time. The Tang Dynasty horse, which is, you know, a symbol of beauty. This is this figurine and I love the relationship of the body to the horse. They’re sort of bowing to each other. It's a very beautiful piece. It's still one of my favorite pieces. One of the first pieces my eyes gazed upon when I entered the museum as I was about to teach. So that's the beginning point with my relationship to Chicago and teaching. But I love this circular motion, the slowness of it.

And then when I left I got this beautiful orchid as a gift. I was leaving my studio and I was going to Michigan, it was COVID. And this artist, Maria Pinto who's an amazing designer and whose clothes I wear sometimes. She was leaving her studio and she had these beautiful orchids and she said, you can take an orchid. So I took an orchid and that orchid still blooms. I just used the idea of the gift as a way to say thank you. I have this wonky way of combining things, so that's how I got to these paintings.

Ajay Kurian: They're really rich and they feel so alive, but the way you were talking about leaving teaching and this being a sendoff too. It made me even look at this sculpture differently. It feels like there is something more melancholic about it, but I'm curious, was this a way of almost making a celebration for yourself?

Candida Alvarez: Oh, yeah.

Ajay Kurian: It shows.

Candida Alvarez: It’s about making it present and you give it visibility. You give a certain amount of time visibility. You can create a painting that can hold something particular. For me, I needed to do this. That's kind of how I work. You know, I just have these ideas and I wanna put 'em together.

Ajay Kurian: So with the Bob Thompson show, how did this come together?

Candida Alvarez: Richard Gray Gallery were doing these shows where they invited artists to work together. They came to the studio and they saw I had a Bob Thompson, and that I liked Bob. I had a beautiful card that I've had for a long time. And they said, would you like to show with Bob Thompson? It's been amazing. I'm still working with him and I'm still making more paintings, but the show is six paintings that I had to create. I loved it. It was beautiful. It was magical. I like having conversations with artists, and to have a conversation with him felt right. He died so young and so I wonder if he would've been an abstract painter. I mean, he was going that way, right?

Ajay Kurian: Yeah. He definitely was.

Candida Alvarez: But I just wanted to talk to him. It's kind of nice to have this sort of conversation.

Ajay Kurian: There’s paintings before this from your show at Gavlak in Los Angeles, which I’ll show in a minute, but the way that you’re developing layers there is very different from here. Say this one, where everything feels like it’s on the same surface.

It's very flat and it's very matte. Then there are other paintings before this, where there’s layers you can see through the paint and you can see other things happening. It almost reminds me of when we see early to mid de Kooning versus late de Kooning where the mark gets much more fluid and soft and there's a serenity to it.

Ajay Kurian: And I'm wondering, does it feel like that's where you're at? Does that relate to you? Do you think about late de Kooning when you're making works like this?

Candida Alvarez: I have worked with De Kooning.

Ajay Kurian: You've worked with De Kooning?

Candida Alvarez: I've created paintings with de Kooning. I've been in conversation with a lot of artists. I used to see excavation painting almost every day on my way to classes. It was always in there. I mean, the museum is very important to me.

Because I'm always looking at things. So there are residues; the coloration, there's something about the whole notion of excavation. In a biography that was written on him, he was talking about how he was looking at this particular scene from a movie. There was a group of women and there was some kind of little fight that happened in the rice patties. He claims that that has something to do with how he painted the painting excavation. Which I found really interesting. So I looked at the film too and said, wow, this could be really interesting.

Looking at excavation, I was trying to dismantle it. I was trying to understand it. It's a curious painting and I love that he uses women. I mean when you look at his paintings, he has a whole mashup of things. It's a very active painting. I love that it's all like in motion sort of.

Ajay Kurian: These are paintings from the Gavlak show. Where the surface and the way that you're thinking about paint, about movement, about how a painting comes together is very different from the works with Bob Thompson. There's something much more serene about when it moves into an interlocked shape and how that shape lives. I guess since there's always stories that come with these movements and how these things develop, I'm just curious, what are the stories that get you into a place where they can lock together that way?

Candida Alvarez: I don't think about it that way because there's a pathway and I'm interested in composition. I was taught painting, and I was taught that the most important thing in a painting is how you begin the drawing and the composition itself. How do you keep the eye engaged? Where's the opening? It's like a navel. So you have to have a little part for the eye to go into it. Like, I gotta get you in there and then I gotta keep you enraptured enough, I gotta entangle you enough in there to keep you there. So that's my main objective — to keep you looking at the baby. And how do I do that? How do I stay with the painting? It's really a color thing. It's not really the story thing.

When I'm painting, I just really look at how the colors are being activated, how they're becoming families. I love this idea that two or three colors can become a family. And how you start to see the, the third, fourth, fifth, sixth color within the combinations. I love that. So when I start to see that I'm happy. So it's really a seduction, is what I need. It's what I do for myself.

Ajay Kurian: This is what you need right now.

Candida Alvarez: I just need the color to sort of hold me up. I need the alchemy. It's like a fix. I need to see it growing. It's like having a garden, I guess. You know, you flower, you water your garden, and you see all those blooms and they're all really beautiful. There's just something about the feeling it gives me.

Ajay Kurian: You brought up both family and the garden and it makes me think of this quote from the book that you worked on with your colleague, Tim. I've begun to see that it's not just oneself, it's a multitude of selves. For me, that definitely includes the politicized woman who embraces her Puerto Rican heritage and bilingualism, as well as the self-determination to stay out of all the cultural boxes, which threaten my freedom to make choices. It's like you have a family of selves in your work too. You've had so many different ways of being that manifest through the way that you make and like what gives you the support and what gives you that flowering.

Go see the show at El Museo del Barrio. Because you can see a person, where even in the darkest moments of it, there's so much joy. There's always joy in how you make and how you think about being alive no matter what happens.

Candida Alvarez: Oh, thank you. At the end of the day, it's about my freedom to choose and to determine the outcome, right? There's not too many other path careers that I can think of where you could do that. So I say, you know, the choice is yours. I mean, it's mine to make and why not make it?

And so, there’s a name for what I do, right? They say it's art. And I became the artist. I'm still becoming the artist. I think we have to just, you know, words and the limitations of what that is. I think enjoyment and pleasure is number one. And I guess, doing this for as long as I've been doing it, I don't feel old. I feel it gives me so much potential and opportunity and joy.

Ajay Kurian: Who said you're old!

Candida Alvarez: I know, but if I tell you how old I am and how many years I've been doing this, it's a long time. But for me it always feels brand new.

And so I don't really work well with this idea of repetition. I kind of always wanna reinvent something. So even the way I break away from my own systems, you know, I develop systems and then I break them apart again. It's like Legos, you can either follow the rules and build that truck or you could just do it your way and get to something else.

Ajay Kurian: I wanna end before we take questions with one of the prior Candida talks. This is from the lecture that she gave at Skowhegan. And I just loved this question and I loved the answer even more.

*****

Recording from Candida’s Lecture at Skowhegan School of Painting (2023

Audience Question: What is your favorite part of being an artist?

Candida Alvarez: I love following what I love. I love painting. I love color because it lives. I love the freedom to be myself. I give myself my own permissions. I feel like creativity is the most wonderful gift that we have as human beings. I feel that you have to be courageous in your life, and you have to say yes to the things that you want for yourself.

It's not easy to get that. Certainly not. You know, it's a challenge being honest to yourself. But at some point in your life you realize you're either gonna go for it now or it's never gonna happen. So I say take courage and say yes to the things you really want. And sometimes it takes time to figure that out. It's a slow journey. It's one step at a time and you always make mistakes. But I always say paintings have to make mistakes. You have the mistakes of invaluable. That's how you get to your work.

*****

Ajay Kurian: Are there any questions that people have for Candida?

Audience Member: First of all, thank you so much for your words and your energy. I'm curious around you as an educator as well. What is your philosophy or your mission as an educator? You also say that you're not too fond of familiarity and has the philosophy and mission changed over the years?

Candida Alvarez: What is my philosophy? Be yourself. Learn as much as you can and don't be afraid to break the rules. I never thought I'd be teaching and I didn't plan on it. I think to be a good communicator is a must for teaching. So I think to be honest and to try as many things out as you can. Learning is, it's just kind of bumping into things that you didn't expect and to. You have to learn the basics, right? And so you have to be skilled and you have to commit. I've always been who I am. So just be yourself and find joy in that, and not everybody's gonna agree with you, right?

You're gonna feel bad along the way too, because you're gonna say, oh man, what did I just do? I can't explain myself. You know, there’s just a mystery to it too. And I think going back to the mistakes — mistakes could be some of the most empowering things, right? When you understand that it really wasn't a mistake, it's just something fresh and new and unexpected, and you have to kind of reconsider it.

Surprises are gifts. I think not to be so afraid of the unknown. Just the power to be yourself is so amazingly important, and we have to own that. We would be happier if we would just be more content with ourselves and that's something you learn. You have to learn that or unlearn something else. Because there's a lot of pain that we suffer too, in that evolution. Oh, I wanna be an artist. And you're like, what is that? If you don't come from a family that appreciates that. It was a word that I had to understand. I didn't know what it was. It was a hard word to utter — I'm an artist. I am an artist though. But I mean, you could do anything. You could write, you could play the violin, you could tap dance. Like I said before, creativity is everything. Right. It makes us all happier.

Audience Member: I have a lot of questions, but I'll choose one. I think a lot of people here are probably artists or have artistic endeavors, but for me, I've been struggling mostly with the idea of an audience. Art is such a personal, intimate thing that you do for yourself in so many ways, and even separate from making a career out of it. But there always is an audience outside of yourself. You touched on it a little bit, that a lot of this work is so personal and cathartic in some ways, but how do you balance that? Is it ever for other people more than for yourself or how do you try to navigate that?

Candida Alvarez: Honestly, I never thought there would be an audience. I didn't know that there would be an audience. I didn't know that I would continue to do this in this way. I had to learn it. I had to trust something. I had to listen out for it. I trusted my teachers, you know, I listened, I made mistakes. I was really shy as a kid. I had to really move slowly and try different things and feel like I failed at 'em, you know?

Unless you're a performance artist then the audience is really important, right? I mean, I think that those are the things that might keep you from doing the actual things you need to do, because you're so preoccupied with this other notion of who's right or who's more right than you.

I mean, we were talking about that earlier. The fear of public speaking, you know, until one day you realize, well, you could only speak for yourself, right? And so trusting that is a big deal. When does that happen? Like when do you feel you've crossed that bridge? I really do believe in what I'm saying, or even better, it's like I'm finding the language that I need to explain what it is that I'm trying to do.

And so I think we can find that language in so many different places. It doesn't have to be just from the painting catalogs. There's so many ways to riff and to trust this material. You have to trust the material that you're choosing.

Or maybe it chooses you, I don't know. Sometimes you trip into something, I think to ponder and to have the time to consider is huge. Not everybody has that time.

Audience Member: It's a privilege, yeah.

Candida Alvarez: Right, so I think that whatever time we do get is to use it wisely. And not flounder so much. We waste a lot of time too.

Ajay Kurian: We can get one more question.

Audience Member: Your work often moves between abstraction and figuration. In pieces like John Street series 12, there's a center of fragment memory embedding urban architecture, right? So how do you see drawing, especially in charcoal, functioning, not just as a medium, but as a language for claiming personal and cultural stories that are often overlooked or a race in dominant narrative?

Candida Alvarez: That's a huge question. Drawing is basic, right? I mean, as a kid you have to learn the alphabet. You kind of have to string that alphabet together to form words. It's fundamental within our core. So drawing is fundamental, I think.

Your question is so multifaceted. I don't know if I get it or if I can even jab at it a bit. I just wanna say that nothing is ever certain. I think the beginning point is a beginning point, but you never really know or understand where that is. And then how that takes root and then how you can cross how you begin to expand that with real roots or threads that really become the fiber of your intelligence and your memory, your love of the realities of life.

I mean, there's so many ways to be in the world, to be present, to be able to be creative, but yet still be more of a historian, right? Or seeking histories of cultures that are still misunderstood. To sort of figure out how we all do come together. You know how diaspora really does live as a heartbeat.

It's complex because you can thread this in so many different ways. Landscape is not just horizontal. It could also be very vertical, right? So like history, right? I like to think of history like the root of a tree, and sometimes those roots could go for miles and miles and miles. Then it can go up and then it becomes something else. So I think that we just have to fundamentally be creative and free to translate and retranslate and to sort of begin to take on the materiality or the tools that we are clinging towards. Because we all have different relationships to tools. Like I need that pen to really write what I'm thinking, or I need that recorder to sing what I'm feeling, or I need to be in a conversation with somebody — like a historian. To figure out what's next.

So I think that there's so many ways, if you just rely on your creativity, I think you can get to some truth that is for you. And I think everybody in this room can have different ways of finding answers to the same question. So we have to dream and we have to fail too. We have to fail at trying to answer something that just gets deeper the more serious you get about it.

That's why I love what I do because I can keep exploring and I can keep changing my mind. Then I can turn it into something else, and I can stop when I want to. I love having that kind of space that I'm in control of.

Ajay Kurian: Thank you everybody and give it up again for Candida!

Candida Alvarez: Thank you!

Share this post