Ajay Kurian: I've been trying to think of a way to aptly describe what it is that Salome Asega does because the way she's thinking about a practice, artistic and otherwise is something that is hard to recognize if we maintain the terms of our discernment into what an art practice is meant to look like. But once you see what she's up to, you can't unsee it and you start to see how this paradigm is one we need to cultivate. With that in mind. The phrase I've come to is that Salome is a culture gardener. She knows which introductions to make, which bee needs what flower, and she gets that the ecosystems are stronger than individuals, more nimble, less brittle. She also understands that in her words, inclusion ain't shit. What she's after is equity, and that means understanding that specific and specialized needs are met. Like which plants need more shade and which ones need more light? What does it take to create the conditions for genuine growth? And how do we grow together?

The growth we're accustomed to is the growth of capital, and that's the world we usually live in. To quote her again, right now, there's a group of cis hat white men in Silicon Valley that are actively working to build a future for us. Without our consent, we are living in their imagination, and I'm very interested in leveraging the power of collective imagination to present counter futures.

She's done this in projects ranging from Powrplnt to the Iyapo Repository under appointment as an art and tech fellow at the Ford Foundation. Currently, she's the director of New Inc. The New Museum's Own and First Museum led cultural incubator. And with it, she's planting her largest garden yet.

Please give it up for Salome Asega.

Salome Asega: That was really nice – thank you. I think you did the artist talk for me.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, we can just drink now. No, it came to me today when you sent me the radio show. But I think, maybe my first question is how does that term feel to you? How does it feel to try that on?

Salome Asega: I don't know if I've ever asked you this question, but at New Inc I like to ask people if they're an architect or a gardener.

Ajay Kurian: No shit.

Salome Asega: Have I asked you this question? Oh my God. Maybe it's a thing we started after you, but are you an architect or a gardener?

Ajay Kurian: I'm definitely a gardener.

Salome Asega: Why? What's the difference for you?

Ajay Kurian: Okay. Actually, I said that impulsively. The reason I said it impulsively is that the very first show that I ever did in New York, was making a kind of garden as the exhibition. The thrust of the show was to almost think ontologically that everything has a dual status as both garden and gardener, so we have the ability to tend to other things, but we also are a thing that can be tended too. That's been foundational in how I think about a lot of things that I do and also how I see the world moving. It's not as totalizing. I think back then, I was a young artist trying to look for the answer. But I'm really curious, now you have me thinking, what is that difference and what does that mean to you?

Salome Asega: I always answered that I thought I was an architect because I was more interested in creating the infrastructure for things to exist. But then people would read me as a gardener. They said, for the same reason that you just gave, that I was in a habit and practice of tending to and caring for, right? Letting people grow in the ways that felt natural to them.

Ajay Kurian: I think a lot of people have this idea of what architect means, which is this singular genius that feels very male. It feels like it has all this baggage with it. Whereas, considering how you grew up and with all the computer engineers in your background, did it give you a different sense of what architect meant?

Salome Asega: For sure. One of our family activities was taking a computer apart and putting it back together again. Engineering, architecture, all these hard skills were never done singularly, they were always done as a group. You'd want to share this with someone you love, right? So I think that's always been part of my practice. I did my MFA in design and technology at Parsons and I learned all these things around physical computing. Then I would take out all these microprocessors and server motors through the back door, and run the workshops that ended up becoming part of Powrplnt, the Iyapo Repository and a lot of the projects I worked on. But it was never about becoming like a singular genius, coder, programmer on my own.

Ajay Kurian: What was your first relationship to art?

Salome Asega: That's hard to answer because I grew up in a city that didn't have cultural institutions in the way that we have in New York. And so I would count some of my first experiences with art as like my uncles coming over to family gatherings and playing music.

And art is just woven through our culture. I also have another uncle who painted a mural for a local Ethiopian restaurant in Vegas. Having to sit there and do my homework while he's painting – these are some of my early experiences with art. But then in terms of capital A art, I remember in high school learning that there was a James Turrell Installation in the Prada store in the Caesars Palace Casino.

Ajay Kurian: Amazing.

Salome Asega: The performance of going to the strip parking lot, my Toyota Corolla at 16, going through the casino, having the confidence to walk into the Prada store knowing I don't have any money, going to the back and just like sitting there to experience that James Turrell exhibit. And then walking back out through the casino, and being like “I saw art today”.

Ajay Kurian: James Turrell was in your orbit at 16? James Turrell was not in my orbit at 16. How did that happen?

Salome Asega: I had really good teachers in high school, one of which was Mr. Brewster, who ran the AV club. I don't know if you knew this about me, but I used to write and produce a daily 10 minute show for my high school.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, that adds up.

Salome Asega: So I had many late nights where I'd be editing the show with friends and Mr. Brewster would put us onto music. I remember the first album he gave me was a MIA mixtape and he would just feed us art books, so that's how I learned about James Turrell. He also put me onto Marilyn Minter when she did her Las Vegas Billboard project. That’s another experience of getting in the Toyota Carillo and driving down the strip and being like that’s a Marilyn Minter billboard.

Ajay Kurian: Did that feel like it had a different kind of cultural capital to you than what you were familiar with before?

Salome Asega: It read as New York. If I was to go back to my teenage mind, this felt like validated art because it came from a big city.

Ajay Kurian: And you didn't think of Las Vegas as a big city?

Salome Asega: No. No. I was alive for our centennial celebration. I was living there at a time where the city was expanding so quickly around me. We lived on what was considered the edge of town, and now if you look at a map, we're like squarely at the center. We'd have scorpions in our backyard. We no longer have that.

Ajay Kurian: The only thing I'm genuinely intensely afraid of is scorpions.

Salome Asega: They’re so cute.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, we're gonna skip it.

Salome Asega: Okay. Okay.

Ajay Kurian: The other thing that comes to mind, I remember going to Vegas when I was really young, probably actually around 15 or 16, and I don’t remember why exactly. But I went to a very fancy private school, and to get shit on in so many different ways for so many different reasons and also being brown in a school that was largely white; there was something that I couldn't fully articulate yet, but I felt small in a lot of different ways. And clothing was one of the ways where it was like, even if I can't buy these clothes, I want to be able to walk into these stores and take up space. So I remember Vegas being the first time where I got to see if I could flex that. And my family's just like - what is wrong with you? Why does this even matter to you, you're not buying anything? I haven't thought about this in a very long time. I completely forgot that Vegas was the first time that happened. But you see all those stores, all these spaces, and all these things that don't feel like they're for you, but in Vegas it does. Because it's so glitzy.

I'm wondering like. Was that also a place where you were like, okay, I just want permission for all of these spaces?

Salome Asega: Yeah, Vegas very much is a playground. I think for that reason it’s a place that is studied by designers and architects, because the city's design allows for this kind of performance and fantasy. You can be whoever you want there and the architecture encourages that actually. So I think combining that strip design with the kind of fantasy of the desert itself, the spiritual aspect of the desert, which is also a place where you can metamorphosize. You can be whoever you wanna be. I think I was encouraged by design to experiment and play, based on where I grew up.

Ajay Kurian: That, in a sense, makes it feel like it's possible to integrate the spiritual and the material.

Salome Asega: I feel like I know what you're gonna pull up.

Ajay Kurian: This project came to mind. One, because it's treating technology in such a different way, which feels foundational to the way that I see you treating technology routinely. Disembodiment towards embodiment, it's always to take you back to your body in a different way. It's always to extend yourself, but it's in a way that feels generative that I don't know if people always think about it that way. Could you talk about how this project started to come about and where this came from?

Salome Asega: I think I started these VR sketches called possession when I was in grad school and I was given one of the first Oculus headsets, like it was a dev kit and it didn't even have a fancy name yet. It wasn't on the market, it was meant for artists to just play and experiment with.

Ajay Kurian: How did that happen?

Salome Asega: I got it through Parsons because I was a student there and taught there, so I would just play with it.

Ajay Kurian: That's amazing.

Salome Asega: No one was using it, so I was like, let's see what this does. Then I started developing these underwater scenes that were thinking about what Mami Wata’s home would look like. Mami Wata is an Orisha that shows up in Caribbean and West African spiritual traditions like Santeria and Yoruba. And when I was looking at possession sculptures around Mami Wata, there were all these figures that had this kind of blobby Orisha, like over a figurative human head. It was as if the orisha was mounting the person like the same way that you would put on a VR headset.

So that's why I started working on these sketches that were thinking about the headset as an Orisha that you put on and then it takes you to whatever realm of the spirit. This ended up being part of a show that the curator Ali Rosa-Salas, who runs Abrons Art Center now organized at Knockdown Center, but it's since grown. So these images are just sketches, but there's a full VR film where I interviewed spiritual practitioners who've had experiences of being possessed by Mami Wata herself. In the film they recount their experience, what it felt like and where they were. Many of them were near bodies of water, and that's where they felt her spirit and felt called to the water. Two of the practitioners in particular said that they felt lured underwater to her palace and were promised attractiveness and great wealth. So yeah, it goes through that narrative with them.

Ajay Kurian: Wow. That feels like Vegas too.

Salome Asega: Yeah, that's true, very slot machine.

Ajay Kurian: That there's a pull and it takes you somewhere that feels like it will make you more.

Salome Asega: Then I worked with a musician, Dani Des, to score the film. You hear one of their beats and it's very undulating and wavelike, and then feels like it's pulling you under the water.

Ajay Kurian: So this takes shape when you're at Parsons.

Salome Asega: Yeah, when I was an instructor. Especially in the early years, I was just like, what can I get out of this program? I think that's why many artists who work with technologies continue to teach, because that's where you get access to all the emerging tools. So I stuck around for five, six years.

Ajay Kurian: It's interesting that you went through an MFA program. That's unexpected for me in understanding how your practice has developed since then, and how distributed it is. Because the MFA is something that normally consolidates an artist's output. Yeah. And turns it into a kind of product sometimes, for better or for worse. But you've avoided that and it doesn't even seem like it crossed your mind that's what you needed to do.

Salome Asega: No, but I did a very untraditional MFA program. I did design and technology at Parsons.

Ajay Kurian: So you weren't in the art program?

Salome Asega: No, but there was a crossover and some instructors who taught between two programs. That was pretty common at Parsons for there to be some overlap between all the programs within the school.

Ajay Kurian: When you were making this, did you make a distinction between Art with a capital A or cultural production?

Salome Asega: No, I was thinking about audience, but I wasn't thinking about how this will be a job, if that makes sense. I was just having fun following my nose, driven by total curiosity and was like thinking – how can I ask stronger questions? I'm looking at American Artist because we both taught in that program for a while too. It's unusual for that program because most people go in there with commercial endeavors. Like they want to work for the big studios. But there’s like a handful of us that are like, we are freaky and we wanna do artsy things.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah. I felt The New School, that was where I met more of the misfits. And the history of that school is unbelievably polluted at this point. But it starts with people that are fleeing and they're the intellectuals of Europe that are making The New School for social research. That felt vital. Was that the community or was it really just the design nerds and the people that were like, okay, we wanna do something different.

Salome Asega: Yeah, I think it was more design nerds and then again, a small handful of us. But some incredible artists have come out of that program. That's how I met Elise Smith. She was a year ahead of me in that program. And we were both like, what are we doing here and let's talk about our work and create a smaller community within this program.

Ajay Kurian: Okay, so you're not thinking about jobs. But when you graduate, what's your first job?

Salome Asega: I'm still not thinking about jobs. What did I do to make money? I hustled. Because I had all these coding skills, I started working with different music venues to design stages and wearables for musicians. Weird, weird stuff. If you go deep on a YouTube search, you can find these propeller hats I made for a band. Do you know L’Rain?

Ajay Kurian: Yeah.

Salome Asega: So before Taja Cheek started L’Rain, she was in a band called Throw Vision. I would do set visuals for her and make wearables, and I would create interactive apps for attendees and party goers to control the stage lighting and the visuals behind them. I would spend so much time doing this and barely was able to pay rent, but I was like, I'm hustling. It's the New York thing. I was also part of the team that put together that lighting grid in the back of Baby’s Alright. That was all made on processing, like open source free software. I'm sure it's crazy advanced now, but in 2014, if you peeked behind, you'd be like, this is not safe.

Ajay Kurian: So you really do follow your nose. It really is a generative place where this leads to this and this is exciting. So what's the next thing? How does that start to translate into the next project for you?

Salome Asega: At that point, I was working on a few small projects and then I started collaborating with an artist named Ayodamola Okunseinde.

He also came out of Parsons and we spent a summer doing research, throwing ideas back and forth, came up with Iyapo Repository, applied to a residency program with Eyebeam and did that for a year. That residency came with significant support, and from that I was able to hop around fellowships and residencies with this project.

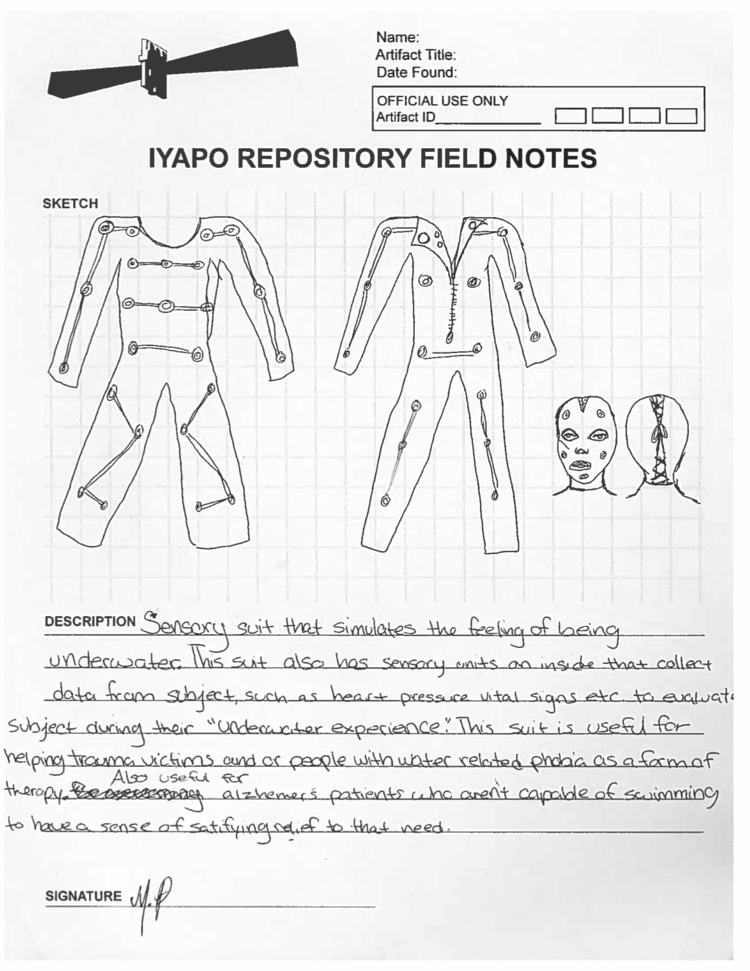

Ajay Kurian: This is a project that particularly grabbed my attention, specifically this artifact. So if you can just give some background of what the Iyapo Repository is and then we can get into this particular project.

Salome Asega: Totally. So Iyapo Repository is a resource library that exists in a non-descript future. It houses a collection of art and artifacts made by and for people of African descent and how we design and develop those artifacts. It happens through a part series of participatory workshops where we invite people to think about the future in different domains. So we developed this card game, with PJ who works at New Inc now. He ran a wonderful print studio called Endless Editions, which still exists, and you should print things there. But we developed this game where we would give people these cards and then they'd have to determine artifacts. If you were given this set of cards, you'd have to come up with a revolutionary tool, an educational tool that somehow incorporates a motor. So you have a design direction, right? A domain you're designing for, and then some physical quality the object must have.

It was always so fun doing this with kids because they'd be like “I don't know”. And then they'd come up with the wildest ideas. So you sketch your artifact design on this manuscript sheet, you describe it, you sign it, and then we collected all these papers and archive them in what we call the manuscript division. There are over 600 of them at this point. We've traveled all over the country and some international places doing this

.

This in itself was such an exciting part of the project for me. The ones that we can materially realize, we work with people to build out. Like that suit you saw sketched out, someone was thinking about their personal and historical relationship to water. She wanted to build a sensory suit that gives you the calming sensation of being underwater. She's thinking about the transatlantic slave trade experience. She's thinking about a lot of things. So then we built the suit to her standards. It’s fully functioning, there's motors at each one of these cuffs that are tied to tidal patterns of the Atlantic Ocean. So you get this nice undulating vibration on your body. There are these pipes that are whirled around your limbs and you can actually hear the water whirring. Then we make films with all of the artifacts because when you see them in exhibition context, they just sit still.

Ajay Kurian: I watched that film and on the one hand it was magnificent to see that drawing come to life. The other thing that felt interesting and perplexing was to think about the transatlantic slave trade and then to have a design suit that also feels like shackles. It felt like a really charged, complicated work where the thing that's giving you life and giving you peace, also has this shadow of something that's much darker.

Salome Asega: Totally. These are all things that come up in our workshop conversations. Once we draw these artifacts, we talk about them. And for her, she didn't see them as shackles. She saw them as almost like seaweed, like getting trapped in like coral and seaweed. But I hear you, there's so many ways to read this image.

Ajay Kurian: There’s a complexity to it. It doesn't fulfill what we think about design objects or like design artifacts, which is it has a purpose, and it serves it. This is loaded and layered and maybe contradictory. Maybe it does have the sense of something wrapping around you and envelops you, but also what else can that mean and what are the histories that are applied here. What part was more interesting to you? The conversations or the object coming to life?

Salome Asega: The conversations by far. These objects are a nice output of what transpired over the course of weeks and sometimes months with a group of people. But this is a conversation starter for me. You see this, and then I'm like, let's do the workshop together. Let's play the game and see what you come up with. I was never really interested in just touring the objects. They needed all the context. And actually oftentimes when these were in exhibitions, there was always a table for people to continue to contribute to the manuscripts.

Ajay Kurian: Oh, wow. The card game itself is a very specific thing. To understand how to create openness and create parameters that allow for that openness to be generative. A lot of times, especially in interview context, people ask things of artists and they're like, what do you think about AI? Like where do we start? It stops the conversation. It ends openness because it's just too vast. But giving parameters and giving a sense like of where you really want to go and what that can spark, that's a really specific skillset.

Salome Asega: There's a term in design for this, it's called scaffolding. You can't just throw people into the deep end, but you really need to create some kind of structure that guides people to a place where they feel safe enough to then be explorative.

Ajay Kurian: That makes a lot of sense. I'm glad I now know that word. So does Powrplnt grow out of these kinds of projects?

Salome Asega: Yeah, absolutely. The first year I did this, I gave a talk at New Inc before it was officially New Inc. And that's where I met Angelina Dreem and Anibal Luque. They were in early conversations about starting Powrplnt, which is a community computer lab. At some point we were calling it a digital art collaboratory. Do you remember when collaboratory was like “the” word?

Ajay Kurian: I don't remember that ever being the word. I'll take your word for it.

Salome Asega: There are these words that start to trend in education and then it's the year for collaboratory. You're like fully in this space now so you'll start to hear it. You're gonna start catching the trends, the words that trend in arts education.

Ajay Kurian: All I can think of now is phonics.

Salome Asega: Inquiry-based learning is another one.

Ajay Kurian: I probably heard that before. I should probably know more of these.

Salome Asega: So the thesis with Powrplnt was how can we hire our friends, or mid-career, or established digital artists to teach the next generation of artists who were coming up in New York so that they didn't have to make the same kinds of mistakes we were making. We were starting to document how an artist sustains their career. We ran workshops that were everything from professional development, legal basics for young artists to deliverable based technology workshops. A really popular one we did was how to make a logo and it was a way to trick young people into learning Illustrator.

Ajay Kurian: Oh wow.

Salome Asega: It was sick because all these people would come out with logos and some of which turned into short-lived brands. So I'd be wearing this shirt or hat that says like hottie. We also ran a really popular music series called Ableton Live, where we would partner with local DJs and musicians to teach the Ableton interface to young people. As part of that, we would sync a bunch of computers and we'd route them through the same mixer. It became an electronic drum circle, all building collectively on one beat. Then we'd strategically place different producers into the circle so they'd hop around and build this beat together with you.

Ajay Kurian: I can't tell if it's because you're in the mix or do you attract that energy?

Salome Asega: What energy?

Ajay Kurian: The energy of doing things together and no one's left out. That there's a way to do this that's fun and exciting, where everyone's included. That's an ethic that even if you're starting a project, even if you're starting an organization and say that's the ethos of what they do. It doesn't always come through, but I feel like every project with you, it always comes through that.

Salome Asega: That's nice to hear.

Ajay Kurian: I mean, it goes with that saying I think anybody in this audience would be like, duh. But I guess the pointed question would be, were you the one saying we should do this, or do these things just bubble up because that's the energy?

Salome Asega: I think it goes both ways. I think as a team at Powrplnt specifically, we were really good about hearing from our neighbors through constant serving and polling, talking with friends, serving them, and creating a program that was responsive to what we were hearing. But also, I think I also have a “let's just try this” energy. Let's just go and throw spaghetti at the wall. It doesn't hurt to try things. And I don't like to do things alone. It's just more fun to test things with friends or co-conspirators.

Ajay Kurian: I was talking to a friend of mine, and she'll be doing a talk with us at some point, Tamika Wood. She considers herself a cultural anthropologist of sorts. Something that she’s had a hard time with is when spaces are too collaborative and there's no leadership at all.

We're all just contributing, but we're not, so what are we contributing to and where's the vision? That's another thing that I think you handle really deftly. There's a vision of what is meant to happen. But when to take a backseat or when to guide. How do you figure out the balance of how to step in and when to step in?

Salome Asega: Yeah, I have a personal anxiety around wasting people's time. I'm just like, it's the New York Minute, everyone's hustling, they're grinding.

Ajay Kurian: I love this small town fantasy of what New Yorkers are doing. Can't waste their time.

Salome Asega: Oh my God, I've been here for 18 years and I still feel that. Or maybe it's 'cause I'm precious about my time. I know how much time I have to do things, right? I think for that reason, I come to potential collaborations with some scaffolding. An idea, some goals, some potential other collaborators. And this can all be edited, but I just wanted to get us started. I think that's important to building cooperative structures. Having some clear goals and targets in mind ahead of just getting people in a room. And then knowing that all of those things can be reworked as people develop trust and get to know each other and the world changes. There are all these external factors that can continue to shape a project, but you need to come in with some sense of why we're gathering.

Ajay Kurian: In that sense, do you feel like you have a relationship with music producers? Like when I hear Rick Rubin talk about the way that he thinks about production, he's a specialist in nothing, and you've talked about being a generalist. What he sees is the essence of a project and then how to shepherd that towards the end goal. I always wonder, why aren't there more? Why isn't there more of that vibe in the art world? I've seen plenty of bloated shows where I'm like if only there was just a place to workshop that show before it comes out. And in the projects that you do, that's the role that you seem to have.

Salome Asega: There's so many things I wanna respond to in what you just said. Do I have a relationship to music producers? I wish I had more. I feel like they're all in their studios, they're working, it's hard and it's a very solitary practice. But I do think that there is something about the way musicians collaborate generally.

I'm thinking about the kind of orchestral experience where you need everyone to make the song. There's a term in jazz called comping that has actually stayed with me since I was just a student at Parsons. Comping is this tradition in jazz where when you start to feel one person in the band slow down or they're slacking, the other musicians will fall back. They'll do that to give that person more space to get their groove going again. And so they'll give them the solo. I think that's how I'm interested in working. I don't need to be the solo all the time. I'm okay with falling back to make sure that the whole band sounds good.

Ajay Kurian: That's amazing. I love all the new terms I'm learning tonight.

Salome Asega: Let’s make a little dictionary,

Ajay Kurian: Takeaways from Salome’s talk. Normally we are in positions where people are pressuring us to speed up, and that in a condition where someone is slowing down, they're either cut or pushed. To give someone space is such an act of love and it allows for such a different kind of creativity to happen. I can't imagine a better way to describe how you create this process. That's really beautiful.

Salome Asega: Thank you. But now you'll notice this. When you go to a jazz show, you'll see they don't even have to say anything to each other. They don't even have to look at each other. The musicians will just slow down. They'll get quiet to allow for someone else to get loud. It's an encouragement. It's your turn.

Ajay Kurian: I really do love that in jazz where the sense between collective and individual is not a contradiction. It's one that's always in motion. So you give that person their solo and then they move back into the collective. And then somebody else has a solo and they move back into the collective. It's a way of thinking, like how is it wrong to shine? There's a way that it can happen where it's still collective energy.

So you're building these things with Powrplnt, it seems like you're still not making distinctions. There's musicians coming in, but also visual artists, and there are people that are thinking about graphic design. That's the space that you're beginning to foster. But then you're also thinking about professional development, which feels like it's more for what we would understand as a professional development for all kinds of artists.

Salome Asega: For anyone. I think when we were all younger, we'd probably tell people, “when I grow up” or “I wanna be”. The beautiful thing about Powrplnt was that a young person would come in and wouldn't say, I aspire to be X, Y, Z. They would very firmly declare “I am a fashion designer, I am here to build my brand – Can you help me take some photos?” I'd be like, yes, here's the camera. For that reason, I think it was easy to support young people 'cause they were so clear about what they wanted to do. It encouraged us to think with latitude about how to make sure that they were gonna make this sustainable.

Even if they didn't wanna go to college or pursue some kind of professional program on their own. Because they were so clear that there were ways for them to easily access the education they needed to make this thing a viable business for real. If that's like getting in touch with an IP expert, a lawyer, we got you. If it's about setting up an LLC, we got you. We can teach you how to do all these things. You don't need to go into debt or go into school if you don't need to. This can be the alternative.

Ajay Kurian: And this is still functioning without you, it’s completely independent?

Salome Asega: Totally. I've been away for probably six years at this point and there's a whole new group of young people who run it and do all the programming.

Ajay Kurian: I want to get to NEW INC, but I feel like the Ford Foundation also plays a role in terms of how you developed, how you understood how art and technology can cohabitate and the space that you can build and foster for people that are thinking in that space.

Salome Asega: Working at Ford was a wild experience. Did I ever tell you about how I got tapped to work there?

Ajay Kurian: I think you were working on a project or was it a consulting thing?

Salome Asega: It was a consulting thing. So I had just given a talk about Iyapo Repository at the Walker. And this person came up to me after my talk named Jenny Toomey, who I know is a really awesome punk musician and was fully in the Riot girl scene. So I'm like, oh my God, it's Jenny Toomey. And she was like, hi, I work at Ford Foundation, I'm a funder, I work on tech and society. And I'm like, what? Okay, maybe it's not who I thought it was. But we connect and we do the email exchange. Then I learned later that it was that Jenny Toomey. There's actually a really strong history of nineties punk musicians working and transitioning into tech policy work, because punk subculture was always invested in decentralized systems. And of course, tech policy is also invested in decentralization.

Ajay Kurian: This is such a touched story. You happened to meet the people that really just sprinkle this perfect magic dust for the next thing. It's so nice, like energy meets energy. But what are the fucking odds?

Salome Asega: I know, I was fangirling the whole time and I was like, what does the Ford Foundation really do? So she wanted me to do a very small consulting project with them. Like I want you to write a two page report on the landscape of art and technology, because we're thinking about how the arts and culture work can start to support artists working in these ways. I overdeliver and write almost a six, eight page memo. She like, it's great, but it was two pages for a reason because people would not read anything longer than that. So I'm like, okay got it.

Ajay Kurian: This is before the New York minute understanding.

Salome Asega: Exactly. So I sent it back and she's like great, now I want you to present it to the director of the Arts and Culture Department. Who at that time was Elizabeth Alexander, another one of my heroes – an incredible poet. I presented and they're like, this is fascinating, we didn't know people were working in these ways, we should be more invested. Then they reach out a couple weeks later and if I want to work there full time as a fellow? And I was like, let me think about it 'cause I was really worried about leaving a studio practice and becoming a funder. I didn't know what that would mean for me and how people would read me in that work.

Ajay Kurian: But what was your studio practice at that point? What did it mean to have a studio practice then?

Salome Asega: At that point I was bouncing around residences, I was giving talks, I was teaching, and I had cobbled together this life that felt to me creative and it was on my terms. As opposed to commuting to Midtown every day.

So I fully blew off the deadline to apply and then Jenny is back in my phone and talked through it a bit more and she was like, I'm an artist and Elizabeth's an artist. Of course you can do this work. So I took the role and it was an incredible four years where I was able to do research with other foundations, the NEA, and help build a landscape study around how artists are making with emerging media. We launched all these incredible grant programs for, for artists directly, but also for arts organizations run by people of color who are experimenting with technology.

Ajay Kurian: Wow, I feel like that's probably when we met, like right around then? It was this round table on cultural appropriation that we were on together. It was you, me, Homi Bhabha, Jacolby Satterwhite, Michelle Kuo, Gregg Bordowitz, and Joan Kee. It was quite the lineup.

Salome Asega: It was a good group of people.

Ajay Kurian: I was reading through it a little bit and it's a fascinating conversation. It's interesting to hear people's perspectives.

Salome Asega: You read it recently?

Ajay Kurian: Today.

Salome Asega: Does it hold up?

Ajay Kurian: There's some interesting problematics that are introduced. I don't even think this made it into the round table, but Greg said something that I still say to this day. He's been an educator for so long and he said that artists come in with their habits and then we turn those habits into a practice. It's just such a beautifully succinct way to talk about how you can really listen to someone and how you can really see what they're up to. So I remember that staying with me. But anyways, that's when we met.

I'm thinking about POWRPLNT to Ford to NEW INC. It feels like almost everything has prepared you to take on a role like this and to really start being the architect. The thing that I'm really interested in here and something that I don't think it's addressed enough is that we are training artists to be stars and not architects. And the star kind of can be manipulated by the architecture. But if we have architects, we can actually build something to develop a whole new idea of what stars look like and what the solo looks like for the collective. I feel like that's what you're interested in and I don't meet that many people that really are interested in that.

For instance, like when I started NewCrits, I was talking to EJ Hill a lot. He was the first person that I was talking to a lot and he loved where it was going. He was totally in and totally on board. I said we can do this together but he said he couldn’t do that. He didn't want to be a part of that structure because he didn't have the bandwidth and that's fine, I'm not putting anything on him. But it became more and more apparent that most artists don't have the bandwidth or that's not the energy that they're looking for. So I'm curious how you've continued to surround yourself with people that are looking for this energy, that want to create these futures differently?

Salome Asega: I don't know. I feel like I've been to these sites where people who are interested in this mode of thinking already gravitate toward.

Being a faculty member at Parsons, the students are there to think about new ways of making, doing, and existing. Then at POWRPLNT, young people bring such optimism and ambition to an idea that it gives me a new perspective. It gives me fuel and fire to think about the world in a new way. And then at New Inc, people are there because they are doing the most courageous thing, which is saying “the thing I care about, the thing I'm passionate about, I want to be my life's work”. I get so emotional at work. My team would tell you, I get weepy all the time 'cause it’s so cool that this person is digging their heels into this project or initiative or business. They're doing it for real and they believe that it should exist. It needs to be birthed into the world and we're here to support them. I'm a little spoiled because I have found the pockets where people are already gravitating towards that.

Ajay Kurian: We were talking about the Laundromat Project. For people who don't know, the Laundromat Project is an incredible organization. One of the people of the organization was telling me that they do bridge loans for artists now, which is unbelievable.

The way he was talking about it brought tears to my eyes just because there's so many artists that have money coming; $3,000 is coming at the end of the month, but for that month there's no fucking money at all. So what do you do? How do you make this work? And so they give a bridge loan. They just give you the $3000, no interest. Once you get the money, you pay it back and they have a zero default rate. It's like those structures where it actually changes the game completely. Like all of these hugely precarious projects can happen. People are thinking, okay, if the system doesn't do this for us, can we just make it? That's the people that I wanna be around. I want to be in rooms with those people. I want to talk to those people. I wanna learn from those people.

Salome Asega: Yeah, it's happening. I feel like that community of people is growing and it's growing very quickly. I think there are a lot of people who are doing work to make sure that artists are involved in larger movement organizing around labor and the economy. I think we're all feeling the pressure and we're all finding each other slowly, but that Laundromat Project example is so good. Those are the kinds of risks and experiments we need Arts organizations to take right now.

Ajay Kurian: Once, they went to a financial institution and they were like, none of this is viable. But they were like, it's our money, so we're just gonna do it. Taking that leap of faith and then realizing, if we love on our artists, the artists will love on us, and we don't have to worry about this. And that feels like a new system.

Salome Asega: Are there other things you're seeing that you're like, this is exciting, like other structures for support?

Ajay Kurian: This is, in a way, a plug, but the Ruth Arts Foundation. I think they’re setting a bar for what foundations can do and how they do it. The level of hospitality and understanding it's not just about throwing a lot of money at somebody and being like, we've supported them and like we can put them on our roster.

Now it's beginning to end. You are a part of a community now. It's the only time where, if I'm ever asked to do something – One, I'm super excited to go 'cause I know I'm gonna be so happy to meet everybody and there's not gonna be one shitty person there. Which is like impossible most of the time.

And the other part of it is that they always pay. There's never a time where you're not compensated for the intellectual labor that you're putting into it. There's just such a grace to it. They'll pay for your travel, they'll pay for your hotel, and then there's a stipend. Everything is considered. There's transport – how you get from A to B, how you get from B to C, how you understand the day, who's there to lead you through, what is the onboarding? All of those things matter. And it's not just perfunctory, I think it's aesthetic too.

It's a practice in itself. That's part of why I was so excited to talk to you is that you exemplify all these things. Like this is your practice and I think people have a hard time understanding what box to put you in or what your practice is. But looking at how New Inc has grown, what it's turned into, and every part of how it functions. It's so fucking hard to do that. It's so hard.

Salome Asega: Oh, that's so nice.

Ajay Kurian: The level that you're doing it at, you are setting another bar and it means a lot to everybody. They don't know how much it means yet. It is an undiscovered entity that is coming into existence. And so what's happening around it is, you're growing, you're sprinkling the dust, you're participating in this kind of longer stream of what's to come.

This is the reason why I wanted to share what Salome shared with me.

Salome Asega: This is how our New Inc brain works.

[Unfortunately we could only show this in person, but imagine a visual board of information that maps out the year through events, travel, initiatives, onboarding, and more.]

Ajay Kurian: Because these flows are like a customer journey. Maybe you have a better way of describing this, but when you're thinking about how somebody enters your organization, like if you're making a show, how does someone enter that show? What does that feel like? Is the floor different? Is the light this way? What is the first thing that they're seeing? All of that is what people who are running organizations think about, especially if they're doing it at the level that Salome is doing it at, where every part of that is considered. There's a real practitioner, there's a real thinker, there's a real artist behind what's happening here. That's why I wanted to show this.

Salome Asega: That's really sweet. This is a really fun, collaborative exercise to do as a team where we think about what the full year looks like. Actually last year we did this just around the corner on this floor. We took over an office space for three days and just mapped out the year.

We call this a program arc. So when New Inc members kick off with us, we do a week-long intensive called camp, where they get a feel for all of our program offerings. And then, in the fall, we go through some foundations of our program and specifically our professional development and mentorships. The thematics of the year are drawn up based on member enrollment information and what people say they wanna focus on during their year with us. And in this example here, the New Inc members wanted to focus on business foundations and ecologies of care.

And then there's a cultivating connect track, which is thinking about how to deepen audience connections or marketing digital strategy. So we do all of the foundations in the fall and then by spring you can focus on one area.

That's when all the programming starts to splinter and you can focus on the one thing you really wanna achieve. Throughout their moments for strategic planning, you can get one-on-one co consultation. This year we brought Sheetal Prajapati, she's a consultant who's helped all kinds of organizations in big moments of transition.

She's worked at Pioneer Works and Eyebeam and, but anyway, it's nice to have access to someone who's built a strategic plan for organizations that are like 10x what you're about to start.

Ajay Kurian: These are things that I think about now. We're trying to figure out systems for ourselves and to construct the institutions of tomorrow. Because yes, it is one thing to create in a way where you're either making objects or installations, and that's a beautiful way to practice. But I am highlighting it because I feel like people don't understand this as a practice and they don't understand that artists should be thinking about this. That this is a space where you can continue the practice, continue the things that you make, but we can also participate in other ways that will put us more in control of what tomorrow looks like, so that it's not run by cis white dudes that have a limited imagination.

Salome Asega: Totally. I did a residency at Project Row Houses in 2017, and at that point I was just starting Powrplnt. I was able to live in one of the row houses in Third Ward and every morning to get stronger wifi, I'd bop down the street to the official Project Row House's office. I'd see Rick Lowe bike into work every morning and I'd get his feedback about starting things like Powrplnt and get his advice on how you balance having a personal creative practice with running an organization. Something that really sunk in for me was that he didn't see Project Row Houses as dissimilar or separate from his creative practice, and that everything fed into each other.

I appreciate what you said about New Inc being part of my work in a deep way. Because it doesn't feel like the job I go to as a nine to five, it’s part of my artistic expression.

Ajay Kurian: There's the outward facing element of it, which is job. But it's almost like Clark Kent being Superman. You have to just be both. There's a way in which that's just cover for what's actually happening. But maybe what I'm trying to do, and what I hope that we're getting out of this conversation is that you don't have to think of them as strict jobs in this way.

There's a different way to think about it and let's actually just reformulate all of it. Let's find a way to actually do it. These are the systems that are eating us alive, so how do we make them so that they work for us? And what do we have to learn to make them work for us? And I'm really glad you're doing that work.

Salome Asega: I'm having fun with it. If you zoom out and go all the way to the left, there's like a pink mural board. I think. You gotta two fingers pinch out. Yeah. And if you go to the left,

This is where it gets wild. This is everyone who's in the program this year. We map out what they do and what they've told us that they care about doing during their year with us. Then we start to build pods of what kind of learning these people need.

Ajay Kurian: This feels like Skowhegan. Sarah Workneh does a similar thing where everything is so beautifully orchestrated that you have these uncanny moments where it's wow, they knew.

Salome Asega: It's about building a culture of hospitality and care, right? We are so lucky that you've chosen to spend a year with us. We have to take that seriously.

Ajay Kurian: Pay attention everyone. I want to open it up. This feels like a good moment to see if there are questions?

Audience Member: Can you tell us more about what New Inc is?

Salome Asega: Totally. We didn't do that. I'm still learning what it is too. but New Inc is a cultural incubator that was founded by the New Museum a little over 10 years ago, and we support about a hundred people annually in launching ambitious projects, nonprofit organizations, and businesses through a robust professional development mentorship program that also includes community events and a shared workspace. We throw an annual festival called Demo that takes place each June, and that's like the culmination of a year with us, where you get to see what people have been working on alongside other creative practitioners.

Audience Member: Is it similar to the Whitney ISP program?

Salome Asega: You've the Whitney ISP, American. What happens there?

American Artist: It’s a lot of reading and lectures, so it’s a little different.

Audience Member: So at New Inc, do you have an idea and a facilitator that will help you?

Salome Asega: Yeah, totally. You get to work one-on-one with a dedicated mentor. You're also assigned to a track of other projects who are doing similar things to you, and you convene once a month to do monthly crits. Then you have access to a pool of 80 to 90 mentors that you can call on for 30 minute appointments to get targeted feedback on something. You get access to seasonal professional development workshops that function more like working groups or more lecture style. In the lead up to Demo, the festival, there's a whole preparation program that helps members get stage ready and media trained.

Audience Member: I love what you said about young people coming to Powrplnt, and I was wondering if you follow the alumni of that program?

Salome Asega: Yeah. Actually I just checked in with the team a couple months ago 'cause they are trying to plan an anniversary moment. And someone we identified that I think is so cool is Mike, you know, the rapper? He used to be in the lab making beats, when we were a popup at Red Bull Studios, but would use our computers for Ableton and would also like film stuff. Yeah, I love Mike.

Ajay Kurian: He's great. He's from Brownsville, right?

Salome Asega: He used to come from Uptown, but maybe he's from Brownsville.

Audience Member: So you have businesses that are part of the events program as well?

Salome Asega: Yeah, we have a mix of people intentionally because that's how we think the network gets stronger. So I actually incubated Powrplnt at New Inc in the third year. Inception.

We needed a logo and some kind of brand identity, and there was a graphic design studio next to us and we were like, can we do a work trade? And so they helped us build our first website and dev designed our first logo so that they could put that in their portfolio to pitch. They were developing a portfolio, so they needed us too and that's the kind of stuff that can happen when people are de-siloed, right?

Ajay Kurian: I think people don't even know that they can ask for things like that. Ithink artists know that they can trade work, but doing a work trade where it's – you need this, I need this. Can we figure something out where we can figure out different rules? That opens up a lot of doors 'cause people don't have the money to do that. There's other ways.

Salome Asega: I think that was what made New Inc so special is that you were in a community of people who were like, this is my grind year. I wanna get all these things done and how can we grow together and accomplish all of our dreams together.

Audience Member: S I’d love to get a peak into the future, as the New Museum enters a new chapter, everything that you’ve learned so far at New Inc, and personally, what are some ideas that you are excited about?

Salome Asega: We’ll just have so much more space in the expanded museum. So I'm thinking about other kinds of programming I can do, even outside of the New Inc sphere. I wanna introduce a regular music series. I wanna do some screenings in our theater. I wanna start bringing in, like this past year, I've been doing studio visits with a bunch of emerging furniture designers. There's a whole scene of design galleries that collect and support furniture designers, but there aren't institutions to show or present this work. There's some curators around the city that do a good job with this. Alexandra Cunningham at Cooper Hewitt does this. Because our museum has been so invested in architecture and design through the expression of the buildings, I wanna see if we can start to be a home for that kind of exhibition making. So maybe some design salons.

Ajay Kurian: I love that, that it's always a thing that's in between, or always the thing that doesn't fit the perfect category.

Audience Member: I was curious about the image on the invitation, could you tell us about that?

Salome Asega: Yeah. So I started doing research when I was at Ford, where I was interviewing black tech policy writers. I was asking them about risk assessment and these newly formed algorithms that cities were purchasing to make all kinds of decisions around social service deliveries. So things from your probation, sentencing, to your welfare benefits, to your public housing subsidies. We’re all being determined, either fully or co-determined by algorithms. And as you can imagine, there are all kinds of very obvious biases. There was this funny term that kept coming up when I was interviewing people where they'd call risk assessment tools rats, because they're these pesky things that have infiltrated risk and social service delivery. So I drew this rat. I first built it in AR. I'd have it propped up in different places and it would play a soundscape of interviews I was doing with those researchers. And then the city of Toronto commissioned me to materialize it, to make it for real. So I spent six months going back and forth to Toronto and making it.

I met with some truck drivers, which was really cool. I learned that the most expensive part of building a monster truck is actually the engine. So it's not drivable, it's more sculptural. But it is forever in Toronto until I can afford to add an engine.

It was so funny because it was parked on the street for a weekend and then we moved it to a plaza area for a month. It has these red beady eyes and you turn the corner and you're like, what is that? Is that a monster truck? And then you start to sit in the plaza and you hear the conversations and I would immediately see people's body language shift, 'cause what they were hearing felt like the wildest podcast.

Ajay Kurian: What made you settle on the monster talk truck as the form?

Salome Asega: Because it was coming fast. Cities were adopting these instruments with lightning speed because it was cheap. We're seeing this now, this year already, the way federal employees are getting cut. And tech policy folks were nervous about how quickly certain departments were shrinking and how people were being replaced with these tools.

Ajay Kurian: And you saw Monster truck shows when you were growing up?

Salome Asega: Yeah. I have a really good photo I should have sent you of my dad and I at a monster jam in middle school. He worked for the MGM Grand Arena, and so it was his responsibility to pick me up from school and then I'd have to hang out at the MGM until my mom got off of work. So I would see the arena turn over for all kinds of things like Janet Jackson concert one night, and then Monster trucks the next.

Ajay Kurian: You grew up in a flex space and now you just keep building up.

Audience Member: good I’m curious, as a multihyphenate, how do you decide what to do next, what to commit to and when to move on?

Ajay Kurian: That's a good question.

Salome Asega: Oof, I'm not good at it. But I think that I am now in a position where I need to say no, but I say yes to things that my friends invite me to do. That feels like the most fun and most rewarding to me right now. Ajay said come through and I said, okay.

Salome Asega: But I wish I had a better answer. I'm just like, do what feels good. Go to places where you feel love. I just think right now, we need to do things that feel healing. We need to be moved by spirit right now.

Ajay Kurian: I don't even know if this is true, so don't quote me on this 'cause this is from Instagram, but apparently a cat's purr is a frequency that helps with bone regeneration. So when your cat's just purring on your body, it's healing you.

Salome Asega: Whoa. I hate cats. But that makes me wanna give them a chance.

Ajay Kurian: I'm not a cat person either, but I'm like, one of the people in New Inc will make a purring machine.

Salome Asega: True. Next application cycle we'll put that in there.

Ajay Kurian: This has been wonderful. I wanna thank everybody for coming! I want to thank Salome so much for doing this. It always means the world to have people that are engaged and interested and want to have these conversations. I always feel lucky to be in conversation with great artists. So thanks again.

Salome Asega: Thank you.

View draft history

Settings

Jan 23, 2025

Share this post