He paints exhaustion, desire, and the ghosts of modern life—Aaron Gilbert on how to stay human in a fractured world

Aaron Gilbert is a painter whose work bridges the mythic and the domestic, capturing moments of intimacy under the weight of spiritual, political, and economic pressure. He’s exhibited internationally and is currently represented by Gladstone Gallery. His paintings are both tender and prophetic, filled with symbolic ruptures, spectral presences, and radiant color.

He explains:

Growing up in a creative family and abandoning a career in engineering to pursue painting—while becoming a father.

Why he doesn’t chase “great art,” but instead builds images that hold his full self—flawed, contradictory, and reaching.

Painting not to reflect the moment, but to prophesize what lies beyond our broken stories.

The struggle to maintain mystery, emotional precision, and resistance within large-scale work.

How brand logos become talismans, color becomes spirit, and art becomes a tear in the fabric of what we think is real.

00:00 Welcome to NewCrits

01:06 “People still seem to fuck—and that’s a good thing.”

02:24 What does it mean to paint history now?

04:07 “I wanted to make the worst WPA paintings ever.”

05:01 Intimacy vs. Monumentality

10:14 Painting the workplace: a shape-shifting host

12:34 From engineering to painting

14:20 Becoming a father and an artist, simultaneously

15:53 “These might be the only paintings I ever make.”

17:01 Art as a lifeline for the socially awkward

20:00 Too private to paint?

24:01 The artist as prophet

30:39 What’s missing in art school? Elders.

37:08 SpongeBob as an exhausted adult

42:45 The levity of “Hot Moms”

47:00 Floating balaclavas and unsolved images

50:00 Spectral figures and ghostly presences

52:00 Medieval symbology and the power of icons

52:53 Giotto and the doorway between worldviews

54:06 Enchantment vs. extraction in Western philosophy

55:03 Mark Fisher, hauntology, and lost futures

56:16 Logos as spiritual metaphors—enter Adidas

57:10 The metaphysics of branding and seduction

59:50 White holes, time loops, and painting as rupture

01:03:15 Against the heroic posture in painting

01:04:24 Imperfection as access to potential

01:09:00 Influence, indebtedness, and divergence

01:13:00 Time as a mystery—Carlo Rovelli and quantum thought

01:14:10 Consciousness, rupture, and looped time

01:15:03 Final thoughts and an invitation to see the work in person

01:16:00 Thank you, Aaron Gilbert

Follow Aaron:

Web: https://www.aaron-studio.com/

Instagram: @aaron_gilbert_studio

Follow Gladstone Gallery:

Learn more about Aaron Gilbert’s exhibition, World Without End, at Gladstone Gallery here.

Web: https://www.gladstonegallery.com/

Instagram: @gladstone.gallery

—

Full Transcript

Ajay Kurian: Hi everybody, I want to thank you all for coming. This is the 19th NewCrits Talk. NewCrits is a global platform for studio mentorship, we have 16 artists on our platform that you can meet with directly, and we offer studio mentorship, professional mentorship, portfolio reviews and contract coaching. It really is a platform to democratize our education.

The one thing that we do in person are these talks. But we're also starting to offer classes. Our first class starts tomorrow, which is called New Identities for Dangerous Times. We'll be offering three more courses in the fall with some more artists that will all be announced soon. Okay, that's it for NewCrits.

We are worn out psychologically, physically, financially, ecologically, spiritually. We've suffered injuries and lost loved ones, limbs and homes. We've struck out and played on lost love and conjured hope. Ours is an age of exhaustion, and Aaron Gilbert paints the exhausted of the earth. The figures in Aaron's paintings are weary, beyond weary, but nevertheless, we see them on dates playing with their children, buying one another with desire and holding one another with heat for all the exhaustion.

People still seem to fuck. And that's a good thing because in a way that erotic charge is hope. A hope for a new tomorrow, for new life, and for survival. Now with all that I saw in Aaron's work, it would still be enough. But what compels me to stay longer is a strange sort of enchanting that many of the paintings hold.

They're pictures that hold their own ruptures in very subtle and sometimes secretive ways. They're paintings of modern life with wormholes to other moments, other feelings, and other spirits. We're not just in the present. We are with the ghosts of many moments and I can't help but think that they're there to help us find redemption. And in the moment we find ourselves in, I welcome all the redemption I can. Please welcome Aaron Gilbert.

Aaron Gilbert: Thank you. That was really beautiful, actually.

Ajay Kurian: How are you feeling?

Aaron Gilbert: I'm good. It's nice to see everyone here.

Ajay Kurian: You got your tequila.

Aaron Gilbert: Yeah, and a room full of people that I'm really happy to have a conversation with. So this is great.

Ajay Kurian: Aaron has a show up at Gladstone Gallery right now. It's up until April 19th and I thought we should just start there. The first thing that crosses my mind, especially looking at older work and now looking at the new show, is that a lot of these paintings feel like history paintings in their own way. How does that sit with you? What do you think about the space of history painting?

Aaron Gilbert: That's really something I was trying to contend with in a very different way. Probably about six years ago, seeing Diego Rivera's murals at the National Palace in Mexico City for the first time. I was really knocked over by the scope and the scale of that project. It felt like a lifelong undertaking. In a way, it felt like a visual form of Howard Zinn’s A People's History of the United States, and it just made me think that there was a much further reach I could do.

There was a much bigger set of questions that I could go for more directly. I think this show was a beginning to me trying to ask and respond to those questions. In a way, I wanted to make like the worst WPA paintings ever made. Not that they're bad paintings, but that they kind of hit at how I feel viscerally about the world that we're living through in relation to what it should be.

Ajay Kurian: When you say the worst WPA paintings, I'm trying to see what energy that conjures in the work, because to me, you tow the line between finding something that feels structural but also extremely intimate. And when I think about murals, intimacy is not the first thing that comes to mind.

Aaron Gilbert: That's where I take issue with a lot of history painting, or where I have maybe a different way of approaching it. I think mine's kind of an inverse, you know? So if you think of a classic history painting; it's like a top down telling of history. Here are archetypes of the workers and here is this historical figure. But for me, what I'm engaged with is this idea of how can I, as someone knowing all these contradictory and all these facets of myself and my life that are pulling in different directions and that are compromised in different ways.

How can I still in some way find a way to be transformative in this world? How do we start with the lives that we actually inhabit and figure out how to move outwards and address these larger societal, historical forces? So it's kind of a reverse process, but with the same set of concerns.

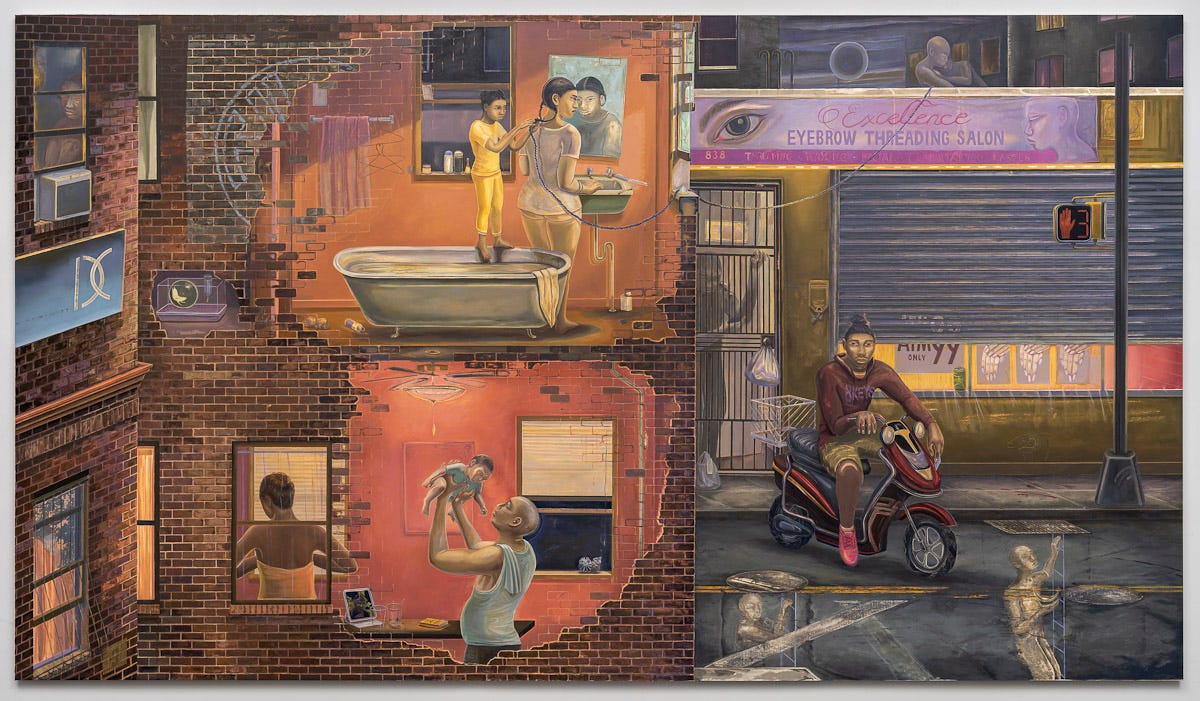

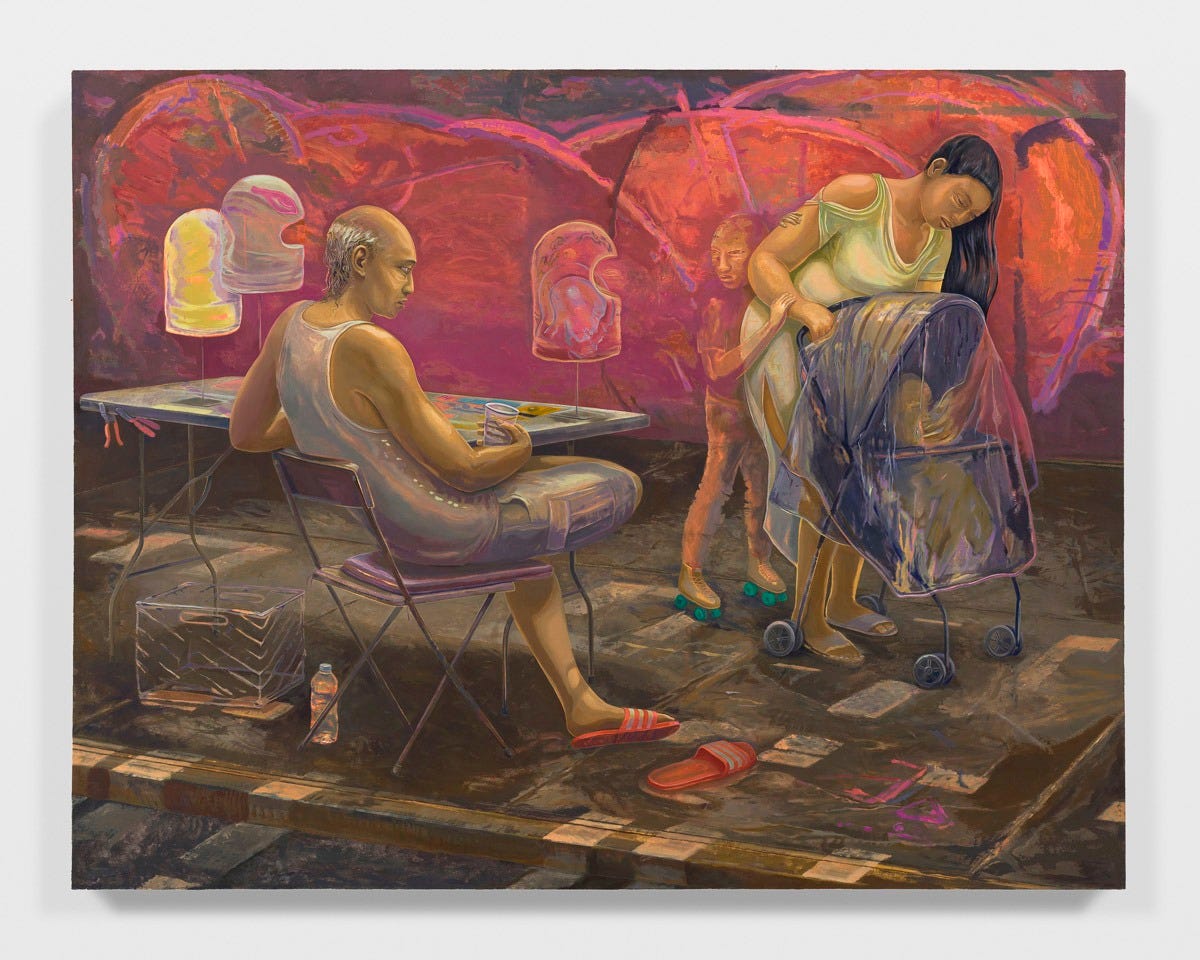

Ajay Kurian: In this painting here, there's so many things going on and so many places to start, but in terms of thinking about particularity first, do you find that structure helps you to then start orienting these stories? Or how does a painting of this vast kind of start coming together in the questions that you're trying to tackle?

Aaron Gilbert: Yeah, so this is a painting I didn't know how to do before I did it, and I just kind of knew that was going to be the case. The way I approach it is I start making drawings and there's a full size work on paper that's the same scale as this drawing. Initially, the painting started with this very small sketch of the mother, and the daughters staying on the tub, braiding her hair. And I liked that gesture. Then I was thinking the mother would be looking out the window and I didn't know where yet, but maybe there's a courtyard. So initially she was ground level. And then because I'm working on paper, I started to think it was a lot more interesting in terms of the power dynamic of her gaze, for her to be higher up and looking down at someone or something outside. Because it was a work on paper, I was able to cut it and move it up.

This was gradually built piece by piece. And the only way I knew to approach it was to start with these small and intimate vignettes, begin to tie them together and think about how to build a full constellation within a piece.

Ajay Kurian: That makes a lot of sense. As soon as I see that scene or focus in on it, I'm like, oh yeah, that's an Aaron Gilbert painting right there. But then to see that become a story that unfolds into other stories and then has a larger constellation within it, is something that structurally makes sense to me. In the early work that I had seen of yours, there's an intimacy that's based in a single room.

Aaron Gilbert: Right, right. It is a very close, self-contained, tight composition.

Ajay Kurian: Yeah, and then in a lot of these paintings, there's something that's happening where there's a zoom-out, there’s different things happening in the same picture, and there’s different gatherings of how people are organizing themselves in different related stories.

Aaron Gilbert: With those earlier works, I was always thinking that the power of this work is if I can have this palpable feeling of larger societal and historical forces. So it might just be a couple in the kitchen preparing food or it could be very self-contained, seemingly. But how can I deliver in a way where you feel these larger social forces and you feel that the figures themselves might have one set of intentions, but then the full weight and gravity of what was happening and what they were doing within the scene was a lot more complex.

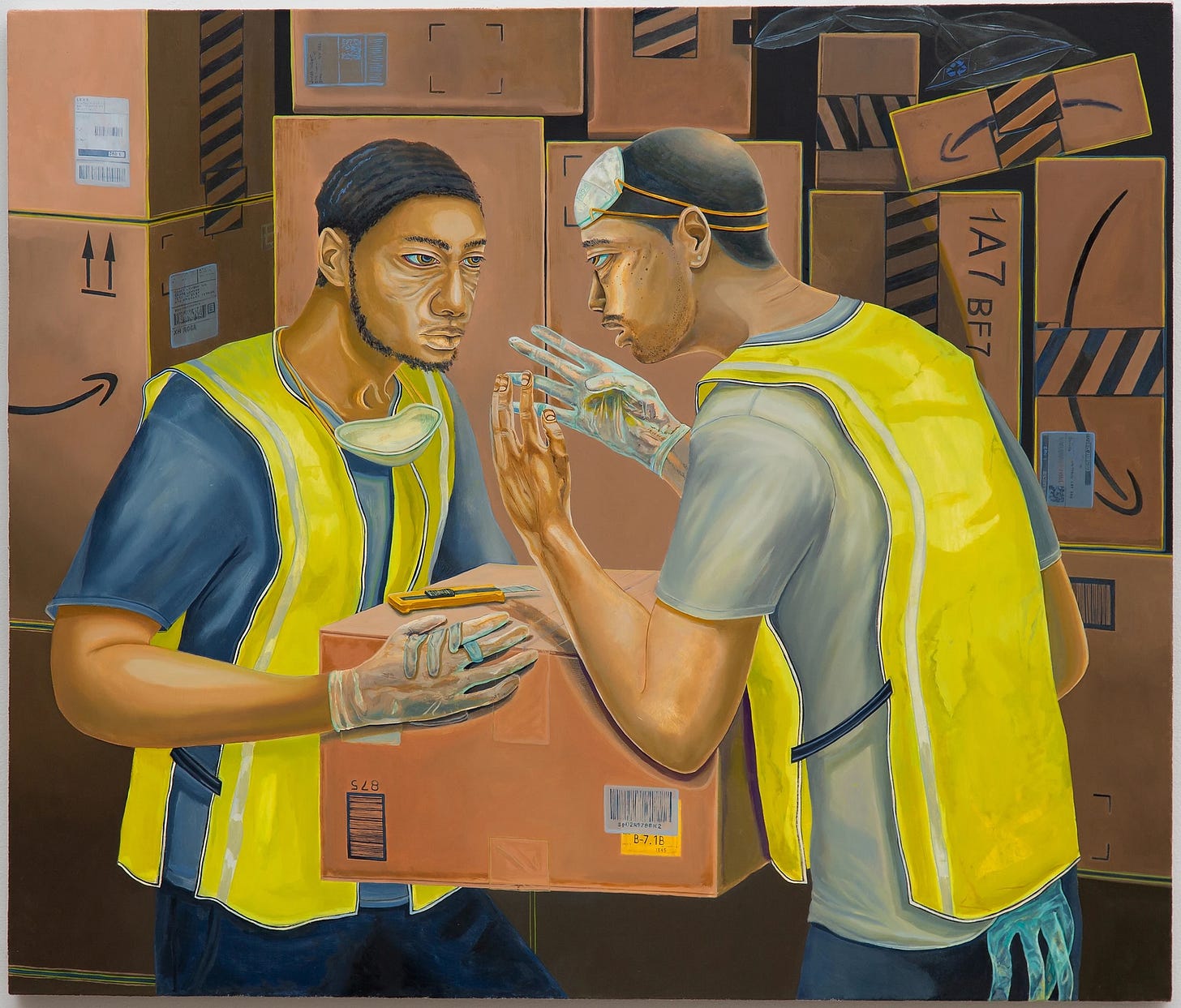

Ajay Kurian: This is a painting that comes to mind, largely because there's so many moments where when I see figures interacting, I understand the intimacy. It is one of the paintings that actually was harder for me to figure out the immediate dynamics. There's something about what's going on between them and what's going on as they function within a system that felt compelling, but also there's a different energy here that I thought was kind of curious.

Aaron Gilbert: In a way, this work was part of a bridge from work that I had been making for at least a decade until this recent show. I'd kind of hit a point where I wanted to broaden the scope of domestic intimacy and find equally intimate scenes. The workplace became an interesting place for me. I wanted to bring it more into the public sphere. When you're working with people five days a week for 8 to 12 hours a day, that’s an incredibly locked in scenario where you really get to know each other and your energies rub off on each other.

So with this painting; I've been working at a fabrication shop for about five years and I was always really interested in how machines and huge pallets of raw materials would get moved around. In a way, the inside of the warehouse was this shape shifting thing that you're living inside of. If you're wearing safety gear, then the patterns and colors of the safety gear are a continuation of the building itself. All the reflective tape to guide people through the building. So it felt kind of like this parasitic host type of relationship. And I wanted to try to just play with that a little bit.

Ajay Kurian: When you started making paintings, what place of thinking did it start with? Did you always have all of these ideas of thinking about how you wanted to make a picture or did it slowly develop? Where did picture making and where did the love of art initially come from?

Aaron Gilbert: It's been a gradual development. I'd say everyone in my immediate family is very creative, so I was kind of the last to dip into visual art in a way. I was studying mechanical engineering and I was working towards an associate degree in engineering technology. I was really not in love with it. The culture of it really didn't sit right with me and I just felt like whatever I'd be making would be a part of a larger destructive machine.

It just felt really against my spirit in the deepest way in terms of what I'd be participating in. But I definitely would not have been bold enough to be an artist without having something that felt like a stable way to make money or support a family. So I started taking art classes when I was studying towards the engineering degree, and then it was a long four year process from when I started taking art classes to when I finally was able to go to art school. And during that time, my son was born. So I also began painting seriously at the same time that I was beginning fatherhood.

Also, the first couple years when I was in art school, I was working multiple jobs. I was getting some time in the studio, but really having to balance it with these different jobs out in the world, was really physically taxing but also kind of really interesting.

Maybe one more thing I'll say that was really important is, because of being a father also, I knew I couldn't try everything that I was interested in. I felt right away that I had one shot at this. I have to find something that feels like I can really run with it and I have to go as fast and far as I can with that.

Ajay Kurian: And at that moment you thought, I can be a painter?

Aaron Gilbert: At that moment, I thought these three years I was at Rhode Island School of Design might be the only time I make paintings. You know, like 15 years later I might be pulling my paintings out from under the bed to show my kids to say this is what I did. So I wanted to really love what I did, and I wanted to really believe it. I wanted it to matter to me, and I wanted there to be enough of me in it. I mean, honestly, I didn't think that people made careers out of this.

Ajay Kurian: Taking those initial art classes, I can understand that to have been a way for you to find an outlet for something, or a way to see, okay, what is it that I want to do? But the fact that it really became the beating heart of your creative life — that’s a profound thing. What were those initial art classes?

Aaron Gilbert: Oh, it was just like a beginning drawing type of art class. Like a lot of artists, I'm pretty socially awkward and reclusive. I don't like small talk or chatter and like I didn’t want to make artwork that was this doorway to being able to have conversations with somebody out there about things that were rolling around in my head. I just wanted to put something else up for people to sink their teeth into.

Ajay Kurian: For one, I think when you're talking about you painting your life and the physical circumstances of everything around you, you never seem to have a problem with putting really personal things into your work. People ask comedians this a lot: where’s the line? What's something that you wouldn't make a joke about? And I was looking at your work and I was wondering if there's something that's too private for Aaron to make a painting about.

Aaron Gilbert: I mean, there's many things that are too private. It's also the spirit of how it's made. I mean, I love being alive and I love people. I feel like if there's something I can make that has a meaningful connection with someone else, and I don't even need to meet them, but if I feel this gravity drawing me towards the making of it then I try to honor and follow that.

I've definitely had moments more so with music where it felt like a song saved my life, you know? Where it was just like I was in this place of being really alone and something just hit me and there was someone else there with me. I've never been interested in being like an edge lord with my work. It's just not what I'm concerned with. I think there is kind of an openness that I'm maybe not even that self-conscious of a lot of times.

Ajay Kurian: I think it's one thing that stood out when you were talking about that was the way that the energy or the spirit in which you paint these seemingly private things, or just feeling the intimacy of a moment. I think what you balance really well is something that feels very quiet, personal and intimate, but there's also something that feels almost mythological about it. That the characters in the paintings are both themselves and the stand-ins. That they're who they are, but they're also maybe shells.

Aaron Gilbert: I think there's a lot in that statement. To pull back for a second, there’s this kind of this larger thing I've been thinking about a lot. This idea of what storytelling is and that it's kind of this concept that we don't live in. We live in our narrative of what the universe is and what the world is. It's kind of like living in a tent within a larger universe. And narrative is how we describe the contours of that to each other and the horizon of what's possible. Then I look at mythology or spirituality as an overlaying of meaning onto that.

So to have this dual thing between, this is a painting of a specific person I might know, or maybe of two or three people who've been combined into one hybrid character. But then maybe painting moves it towards the symbolic or the mythological. What's in the room is partly the individual and then partly this greater thing playing out that has to do with how they're participating in something that is a mystery, that is cosmic, that is beyond what our daily cultural scene is.

Ajay Kurian: Were you the philosopher of the family?

Aaron Gilbert: Oh man, no, no, no. I'd say very different ways. Both sides of the family.

Ajay Kurian: So that was like the milieu, like you’re surrounded by people thinking about grander ideas?

Aaron Gilbert: Grander and worse ideas. When I was in my first semester in undergrad at RISD, I don't even remember what I brought to class, but my work was very rightly being criticized. The teacher was basically saying, I don't see anything of right now in this painting. It feels like you're kind of stuck trying to make something that looks like art, but nothing of this moment is in the painting.

I was talking to my mother on the phone after, and she said an artist's job isn't to reflect the moment. She said the purpose of or one major part of a calling of an artist is the prophetic. I think that was something that's really stuck with me in terms of the work that was with anybody.

Ajay Kurian: My mother has not said that to me.

Aaron Gilbert: And yet here you are. So yeah, similar stories.

Ajay Kurian: Of course, mothers are your first coach, confidant, teacher, all of these things. So I'm sure there's something there. But to establish the prophetic so early in the work and in how you understand the calling of an artist, this is purely for my own curiosity, how does one cultivate the prophetic?

Aaron Gilbert: I've been thinking about it in different ways lately, but maybe to get back to that conversation of not living in the full universe, we're inside this moment and this age within some room that's been built out of a shared and very flawed story. And I feel like whenever we hit the poetic is where there's a terror in the logic.

Because if something's poetic, a linear explanation doesn't really reveal its power. But we feel that some truth has been revealed. It’s something that we can circle around, but the language we have right now doesn't fully deliver what it's delivering. It's this potential. I feel like maybe that's some kind of tear from the other side, penetrating and calling to us to move into a different fuller stage. So I link that to the prophetic in a way.

Ajay Kurian: Do you think that those tears always stay open or that they're historically contingent? Jackson Pollock was somebody that I'd seen in every poster in every college dorm, and I was just like, this is so dead to me. Then much later in life, I remember going to the Met and standing in front of a Pollock and I was like, holy shit. It felt like it tore open again. This is a very sort of modest example but it's happened many times. For some reason that occurs to me right now and there's moments when I feel like a particular artwork has opened, and a particular artwork has closed, and that there's almost an aperture towards another place.

Aaron Gilbert: Yeah, I can see that. That's what you mean by historically contingent. I don't know that I have an answer to that, but I believe it.

Ajay Kurian: Just in terms of your experience, I know that ancient artworks have been really important for you to see how they can stay present for you. Are there times when art feels like it's not living for you that way anymore?

Aaron Gilbert: I think I need to think about that, but maybe what's most generative for me to think about right now is the carrying and passing on of a flame and that we're participating in a continuum. I was just looking at Jack Witten's work today at MoMA, and there was no show I could think of that's less timely than that.

We're here for a very short amount of time, each of us. And something I think about, also with raising children, is seeing the generation before me begin to pass and die. So we need to grab and hold onto the things that they carried to us and reorganize them and deliver them forward into the future. So I guess I think about that more and I don't worry too much about where something feels. I'm just looking for magic where it is and trying to keep those embers.

Ajay Kurian: I remember when I was in your studio that was, I was telling you that I was asking people what they think is missing from art school? And the first thing that came up for you was the fact that we don't really hear from our elders in art school. That it's more like, what's happening now? What's happening here and what's the presence?

Being around older artists where there's a different understanding of what present is, felt really important. I never really thought about that. Of course you have older professors when you're in school, but I didn't think about it in terms of a larger continuum of what is being passed on, what's being preserved, what's being understood, and it's a beautiful thing.

Aaron Gilbert: Well, I think there's something terrible that happens when you're isolated from generations, both younger than you and older than you. That happens in academia and I don't think that's that healthy. In the arts, the relevance of your work is so connected to a sensitivity and read of the societal moment and by only being around your age, the band of what you're receiving becomes narrowed so much that there's a loss of wisdom. I think that something is sacrificed by that.

Ajay Kurian: In thinking about this show, was it in any way different than how you've thought about shows in the past or how you're constructing this story? Because you're thinking about the universe that we live in and that we're just seeing a fraction of the story. Which is almost a way to unpack different stories or narratives that are kind of lying latent. Is that the place in which a show comes from, or is that the place in which the work comes from?

Aaron Gilbert: It's kind of hard to decide what came first. When I was making the work, I really wanted it to be this cohesive thing. And I mean, I haven't done a lot of shows, you know, so this was a great opportunity where all of a sudden I had more than a year to work through and develop a full body of work.

I didn't know what those images would look like. I knew some things that would be in it. And I knew there was an unknown that I really, really, really wanted to move towards. I had no idea what that was or how I'd get there or what it would look like. But then I would just go into the studio and I would need to make something. So I'd be starting with making a painting or making drawings towards a painting. But I had the benefit of having that time to be able to reject something because it might be a nice path, but I don't think it's the right branch to take. There was definitely a lot of testing different things in that sense.

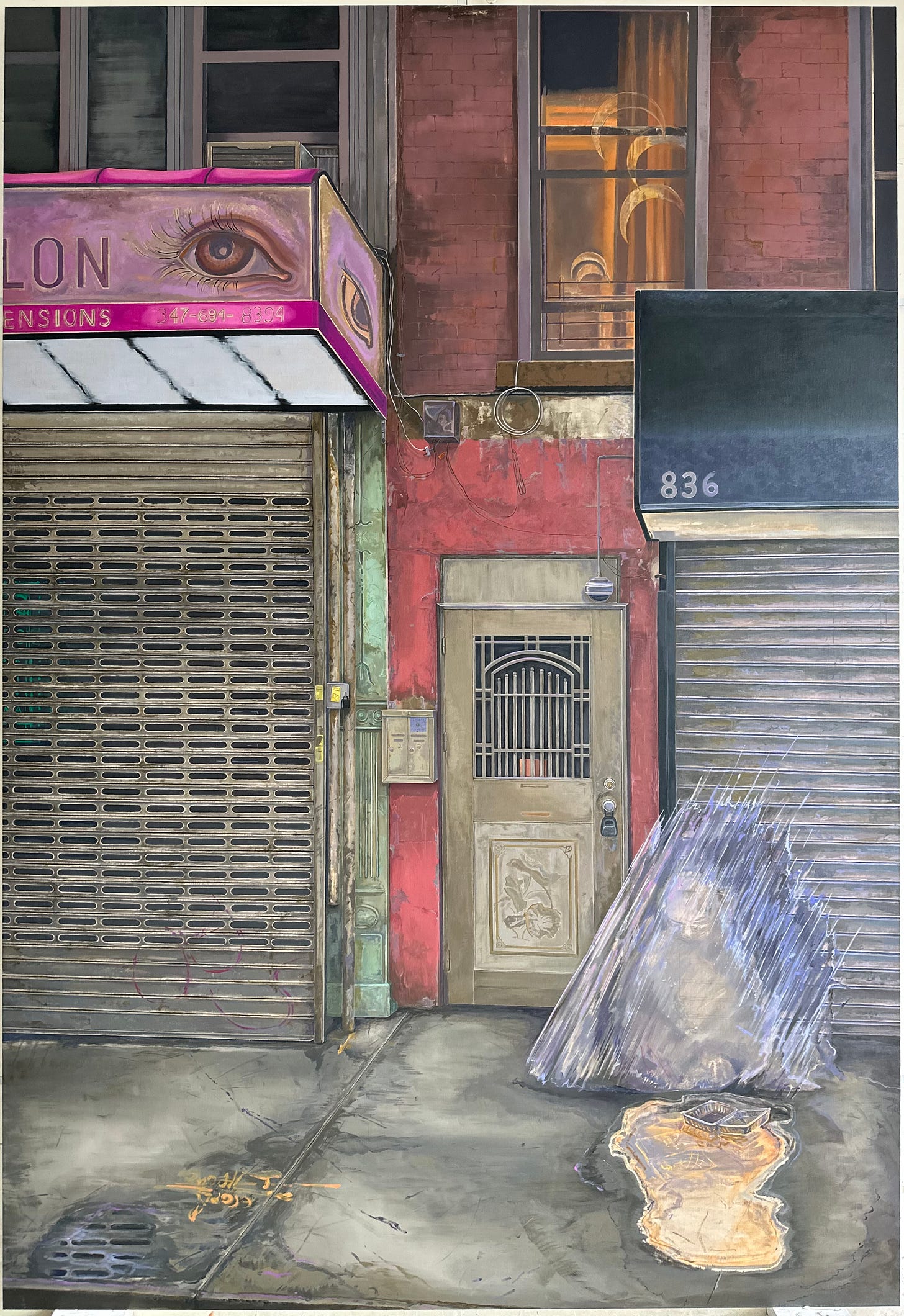

Ajay Kurian: I guess this is the case with every artist, but it's the process of sharpening your deeper intuitions towards a path that consistently feels true and whatever that truth is for you. That’s the basis of so many bodies of work. But seeing this show come together and seeing how both labored and free these paintings feel. They feel extremely precise, but not like there was such a specific plan. Like when I see these kinds of crescent moons up here, there’s a joy there that doesn't feel like it was premeditated. It was just like this image started coming together and then moons were floating and there's nothing left. There's nothing else to explain about that besides the fact that it needs to happen. There's a necessity in the picture.

Aaron Gilbert: I think you're hitting the nail on the head. There are a lot of stages that are really developed and worked through. But if something doesn't surprise me by the end of it, then I feel like the painting was kind of dead on arrival. That I must have slept through the making of it and not really been present.

Ajay Kurian: How much do you get rid of? Do you destroy work?

Aaron Gilbert: I don't usually destroy paintings. There's definitely a lot of unfinished ones. There's a number of ones that probably won't be finished. And I make as many drawings as I can.

Ajay Kurian: You have these drawings of SpongeBob in your studio that were so fucking good. Imagine SpongeBob with the weariness of one of Aaron's figures where they're tired, they’re just so tired. Man, I think about it probably once a week. There’s just something that's so accurate about what I feel like everyone is feeling, paired with the manic personality of SpongeBob.

That's like what you have to do in the world and sometimes I feel like everybody has to be a laughing idiot just to make it through, and then to come home and the depletion in him in those drawings is, it hit me really hard and I can't stop thinking about it.

Aaron Gilbert: One thing I've been thinking about with SpongeBob, like after the fact, is how children are very excited about life and the magic of this world is rejuvenated by the presence of children. They're these messengers from the stars and to them, life should be magical and we should be present and it should be fun. I feel like SpongeBob kind of is all those things. When he arrives at work to flip patties, there's nothing he'd rather be doing, you know?

I’m not saying that's how you should feel about your job, but it's just that excitement about being present. I think with the drawings that we're speaking of, it's more like what happens when you’re in your mid forties and that person is in there somewhere, but there's a lot of miles between them. There's kind of a larger project that it’s a part of, and I really can't wait to share with people.

Ajay Kurian: The fact that it's part of a larger project now, I'm there. I'll fly wherever it's going. When you're talking about children being messengers of the stars, it made me think of this painting and when I first saw it, put me in the strangest place. I think when I initially saw it, or I initially saw an image, and it was as if the child was like an inflatable or there was something so disembodied about the body. The more time I've spent with it, and I guess it also helps that I've heard you talk about it, but this coming from another place and that there is this alien sense of a messenger from somewhere else.

My partner has a son who I've known since he was five, and that was a great time to meet him because there were still these like vapors of other places that you could still kind of be in touch with. And I've heard this from other parents. There's a curator who I was talking to about a show that I'm thinking about, and to the wrong person it would've sounded like a little woo woo. I just didn't know this curator that well yet, so I was just testing it. I was like, this is what it's about, this is what it is, take it or leave it. And she was like, I would've thought that's a little out there, but I have a 3-year-old now and he has had a fully prior life before this, and he’ll tell me about the people he used to meet on his walks home. She was like, I have no explanation, but it is a thorough trip down a series of memories that she can't explain.

Aaron Gilbert: That's incredible.

Ajay Kurian: She was like, that changed everything. There's these moments where life upends all the rules that you know, and you have to obey the enchantment of that.

Aaron Gilbert: That's a wonderful thing though, to have these things that take us from a place that feels tired and constant and predictable into something that reinvents life.

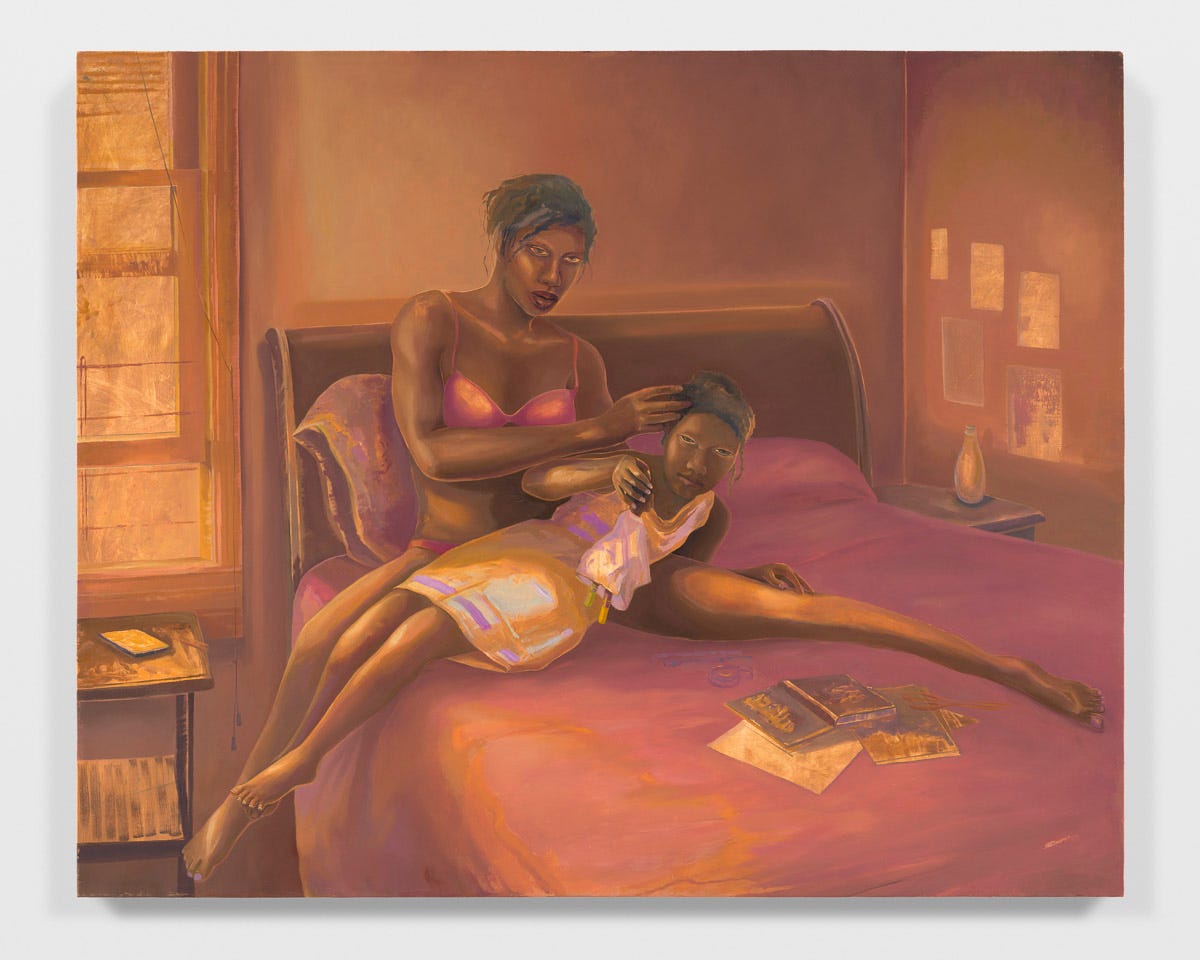

Ajay Kurian: It's the funny place that I also see your work sitting in, where there's a lot of really heavy things in this show alone. We can run the gamut and see everything that life has to offer in a sense. I mean, I feel like I don't even need words for this. There's such a weight, and yet I also feel there's still some kind of levity. There's still the fact that this painting is called Hot Moms.

It's a good way to orient it. It's a good way to sit with it. There's a slowness to everything about it. There's a slowness in how even time itself is making itself manifest in the painting. But it also gives you permission. The title Hot Moms gives you permission to treat it as both super heavy and super light. And I really like that 'cause I, in a sense I feel like, if you don't know how to be dumb, then I don't know how smart you really can be either. You gotta have both. You gotta be able to just fucking be dumb. And I mean that not in a pejorative sense.

Aaron Gilbert: Yeah, I feel you. With this painting, the beginning to me was a small drawing I did of the male figure seated from behind. In my head he was like this older version of myself and I was like, I'll have long, beautiful hair. You know, every morning I'll be looking at myself in the mirror. I'll still have game. I just really want to enjoy this playful and full of vitality vision of a future version of myself. You know, like you have those locks, working on it, and so that was how this started. I just thought it was funny and interesting, but I had no idea what that would lead to.

Ajay Kurian: So that's where it started. I mean, it went a lot of places. Where do the floating balaclavas come in?

Aaron Gilbert: I thought it was interesting how they kind of look like Pacman heads. They could be containers and I liked that they could double as something else, that could be entered, and I just let it take me there.

Then there's parts that to me, were very, very serious. Like the child who's next to the mother. That's a very specific relationship between a child and a mother that's protective and very much, you know, this is my home, this is my world, this is my universe.

In my head, it never was settled and I wanted it to stay open. Whether he was seeing himself as a child, if he was looking at a real child, or if he's looking at a child but not seeing the child, and seeing his younger self instead. And I think all those things can be true at the same time.

Ajay Kurian: There’s a spectral quality there. I feel like there’s a number of ways in which you use the ghost or the specter of something that either has happened or is yet to happen. There's a haunting that happens and it doesn't necessarily have to be a bad thing. We exist with many kinds of beings and it's fascinating to see how that plays out. Because sometimes it's like an actual figure.

There's one painting where there are two circles next to the person's head and it orients you in this way that you lock into that feeling. But it's not explicable as a specific narrative. It's the same way that sometimes color can lock you in. Like seeing that kind of green turquoise of the roller skate wheels, it knocks in a specific feeling, especially since it's one of the coolest tones or it’s so pronounced in a painting of largely warm yellow greens, reds and pinks.

You just see those wheels and you're like, those wheels are here to tell me something because of that color orientation. There’s such a fluidity in the way that that happens in a lot of these paintings where it can be the way that something's painted, that it's here and not here. Or it can be the pronunciation of color that just knocks it into place. It's almost like the symbology is medieval.

Aaron Gilbert: I think a lot of the painting that I've really been influenced by, in terms of the western cannon, is from Giotto and earlier. So I look at a painter like Giotto, which was this moment of a doorway between two worldviews. One was coming from this world being a place that was still inhabited with magic, where the sacred was still present in living and non-living things.

Basically an enchanted world where there is mystery and forces in the presence of the sacred, kind of with this Cartesian philosophy where all matter, all plants, animals, and even humans are raw material meant to be extracted and carved out in service of industry and for profit accumulation.

That philosophy was kind of a necessary underpinning if you look at the larger catastrophes of colonialism and a lot of the things that we're looking at now. The oncoming ecological crisis is also a result. It required this very degenerate narrative or story to be sold.

And I look at a painter like Giotto as someone who’s, whether he realized it or not, work embodies this doorway between those two moments. Historically, a quote that I talk about a lot is when Mark Fisher was writing on ontology and he states that, when we've hit this terminal point in history where we're no longer able to visualize some positive possible version of a future, we need to look back to these past relics for echoes of other possible futures. So I think there are ways that I'm kind of really looking at and riffing off of moves that were in different traditions of paintings that predate. We've hit this wall, so where are there new doorways to find so we can actually move into something different?

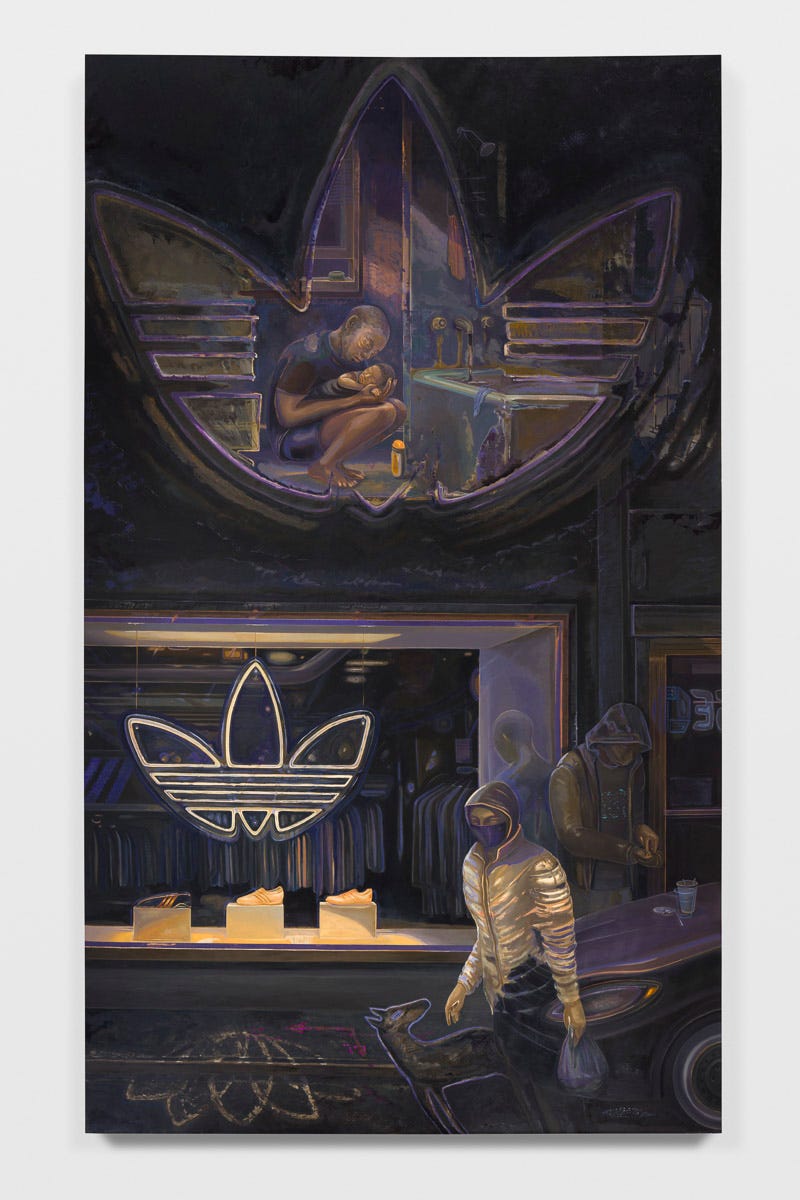

Ajay Kurian: In thinking about doorways and symbols, there's ways in which you're using extremely well-known corporate symbols, but I as a viewer believe that there's something more through the painting. And again, just on a personal level, I'm curious if you believe that the corporate symbol, even though it is couched in a capitalist vocabulary in its inception, can transcend that or can become something else?

Aaron Gilbert: There's a couple parts to that. Firstly, when I'm using these logos, it's because I think they are something more than what their awareness or intention is. I've been thinking a lot about how commodity fetishism is the metaphysics of our moment now. I'm not more interested in Adidas than any other company, but that logo really hit and struck me. I was walking past the storefront at night, I saw it and I was just really drawn in. It felt so seductive, cold, and it vibrated. It's kind of like a lotus and it's definitely pulling from these conscious and unconscious archetypes deep within our psyche.

Secondly, my interest in continuing to play with it is I'm interested in what happens when you read it in the same way you read the religious archetypal image, or religious iconographic symbols. If you look at Catholic paintings, where there's a crucifix or maybe it's 30 other things. When this is placed next to it, I'm interested in what happens.

There’s another Mark Fisher quote where he was talking about the National Gallery in London or something like that. If some visiting extraterrestrials were to see all these things laid out, all the different things that humans believe, but we don't believe in any of them. And he was kind of saying that's the power of capitalism as it can consume everything. But it also doesn't believe in it. It kind of kills the belief in that thing.

So what happens when you put these logos that are the face of commodity fetish, this is the thing that's supposed to draw us in. Like, if you think about angler fish, where it's got that light. That’s what that logo is, in a way. In my mind, that’s that thing that draws me in to participating in something that's gonna devour you. Devour me and devour everything. But can we take that and then bend it and then what? What does it become?

Ajay Kurian: Because I think the bending is really successful. This feels like an aperture to something else. It doesn't feel like an aperture to rapacious capitalism. It feels like it's a window into the conditions of what kind of privation capitalism creates. But it doesn't feel like it lives and dies there, it feels otherworldly too. The fact that you made me believe in the mystical possibility of the Adidas symbol, that's where I was like, well, shit, I guess I like the Adidas symbol.

That's not the takeaway though. But this is the angler fish. I'm thinking about the Adidas symbol in a different realm and it adjusted what plane I'm thinking about it on. That's the success for me.

Ajay Kurian: I feel like now might be a good time to open this up to some questions.

Audience Member: You already talked about this a little bit, but leaning a little bit more into how these spirits or emissaries function. These ghost-like figures appear in so many of your paintings and I'm so drawn to them. Do they function as that terror in the fabric of normal reality that's inviting you to see the world differently and mystical? Do you see them as entities that are coexisting with us? I’d just love to hear how these beings function in your universe.

Aaron Gilbert: I think at the heart of it, there's ways that we're all bridges between what we're aware of, what we know and then things that are a mystery to us. I don't know if it's an either or, in terms of a figure being solid or not. Maybe there's a slipperiness between when the same figure is fully in the room and then also being an opening to something that’s outside.

Audience Member: The way I see your art pieces, especially the one that you created at the beginning which are so beautiful, are on so many stories all together that to me kind of looks like a cabbage. But if we’re talking about your new upcoming project, is that gonna be a bigger universe with the same intense intimacy, or are you gonna keep the bad that you’re leading towards too at the moment? How is that gonna be in the picture?

Aaron Gilbert: I don't know totally yet. I hope there's something in it. I have to grow into making, and I hope that process isn't too painful. But I really believe in the creative act and I think it's something that requires you to let go of what you know to some degree and let go of what you brought into the room to some degree, when you engage with it. The work and the process should guide you into expanding what you’re considering with that piece. I love the cabbage metaphor. It's the first time I've heard that.

Audience Member: I really appreciate the way you've spoken about this vigilance you have or heroic posture when it comes to history painting and the things you inherit through painting that you like don't fuck with.

My question is about what kind of formal or internal questions you bring to your work. Especially in this body of work, where you’ve scaled up and there's a lot of bigger swings that come closer to the ambition, scale and heroism of some of the pain we were talking about before. I'm wondering how you negotiated that. Is it a matter of keeping room for improvisation while not planning too much? When it comes to making sure you keep your paintings from falling into this heroic posture that you don't want?

Aaron Gilbert: What do you mean by heroic posture?

Audience Member: I sort of arrived at that language through the way you're talking about murals and how you want it to be a blank or a bad WPA mural, and what you said about keeping close to your life and the domestic sphere helps you stay away from this archetype painting.

Aaron Gilbert: I mean, I don't know the context of this piece well enough to speak about it directly, but I feel archetypes lack something. When it comes to the very particular thing that I'm trying to accomplish with the work, and what I'm really concerned with, is this question as a human — how can I actually participate in this world right now in a way that's substantial and meaningful and potent and has a positive impact?

I'm really concerned about what is this world that's being passed on to the next generation and what's my role to play in that? So just like tactically speaking, it's important to have the flaws and compromised realities of the characters be foregrounded. Not just flaws, but also the really complex range of who we all are. We aren't these one dimensional like executions of an idea, you know? We have all these different layers to us. So I'm always trying to think of how to develop each character within the image so that, as a viewer, you might walk into it first seeing that figure one way but then also see these other nuances that actually kind of change something about that figure and or change your read of it.

So to get back to the first thing about having the presence of imperfections, it's because I think we can't be so fragile that if our own imperfections become visible, we shatter and no longer are capable of realizing our full potential.

Just this kind of insistence that whatever is absurd about me when I look in the mirror in the morning, and just being able to see that. To look myself in the face and be like, yes, I see that there's all these things that if I could, I would wish differently, but that doesn't have the final say.

And I have this potential to do something that is profound and that's going to be what defines me, whatever my divine cosmic destiny is. Nothing anyone says has a power over that. And I can activate that and articulate that in the world. When I think of the standard social realist artwork, it feels like it's a template that doesn't have the capacity to do that unless these other things are introduced. And so my question is, what are those other things that need to be introduced?

Ajay Kurian: It felt like this has come up before where you were talking about George Tooker’s, and the institution overwhelming the individual. I think we've all seen in Aaron's paintings that there’s a real struggle there that is not completely subsumed. There's still something alive in the individual or in that kind of human intimacy.

Aaron Gilbert: Tooker is a painter who I'm really indebted to. When I started to build what my work could look like, that was like a major influence. Tooker also has this breadth of energy in one painting to the next. But I think overall, the architecture is showing this crushing societal force in the beautiful artworks. I'm always interested in when I find someone who's influencing my work, how do I define how I'm indebted to them? And then how do I define the ways that I'm the antithesis of what they're doing?

Audience Member: Could you talk a little bit about the use of color and your color influence?

Aaron Gilbert: I think about having the light be chromatic, like having there be a color made of the light and atmosphere and a temperature that's palpable or a heat or coolness. I want the light and the atmosphere to actually be like a major character. I want there to be like a frequency that you feel, you know, 'cause I'm not making future JPEGs. I'm making objects and I'm really interested in this idea of a painting as an object that is singular in the world. It's like this instrument or this bell that rings out and when you're in front of it, it alters the frequency of the room. Color is this place beyond language, and that just seems to be everything that a painting is or can be about.

With some of the paintings I made this past year and a half, I didn't know how to make a painting without having that presence of some of the pain that I was experiencing by witnessing the changes that are happening. Color was a way to try to do that.

That's not the only thing, but there's a couple paintings where I point to where it's trying to reduce this palette into something that felt almost like the world had been scraped away from the inside. When I talk about the worst WPA painting, it's like this thing that had been eviscerated and there was a shell that was left.

Ajay Kurian: That's a nice place to end. We're back to where we started with the eviscerated WPA paintings.

I want to end on this just 'cause it felt potent. I know that you've read Carlo Ravelli and have been thinking about time and quantum physics in that regard. I just wanted to know if you had read about this theory on white holes as opposed to black holes.

If there's any physicists out here, please don't quote me on any of this. It's been thought that when things go into a black hole, they are crushed into a singularity and it's gone. Their theory suggests that actually it's more of a bounce that happens and that what gets pulled into the black hole emerges from the white hole in a completely different time. So the white hole is essentially the opposite. Nothing can enter the white hole, only things can exit it. Hmm. And it kind of felt like an interesting conduit to think about how the paintings are sort of pushing out these different tears or like making apparent different tears.

Aaron Gilbert: That's so poetic. Which book was that?

Ajay Kurian: I think it's called White Holes, it’s a relatively new book by Carlo Ravelli.

Aaron Gilbert: What Ajay is referring to also is that when he visited my studio, I talked about this book called The Order of Time by Carlo Ravelli. That is really about the way we commonly think of time breaks when you get at the quantum level and that we're left with something much stranger, and how it quickly enters this conversation of the mystery about human consciousness. So I would love to read that.

Ajay Kurian: You have five more days to see the mysteries of human consciousness in Aaron's work. So I really suggest you go see these objects, these paintings, these real things in person. And I just wanna thank Aaron again tonight. A round of applause for Aaron.

—

Subscribe to our channel for more artist talks, critiques, and conversations that push the boundaries of what art can be.

Stay connected: Website → https://www.newcrits.studio/

Instagram → @newcrits Newsletter → https://newcrits.kit.com/subscribe

Share this post