Studio Visit with Aaron Gilbert: Spongebob, Walter Benjamin, and Redemption

Learning to love the Present

The fact that Aaron Gilbert’s studio is off Broadway in Brooklyn makes perfect sense. Broadway sits under old and monumental subway tracks that obscure light and, at almost all times, ring out like banshees because of the trains above. They could be beautiful, if some context were removed, but they’re monstrous and dystopian if it’s your lived reality. I see this kind of balance in a handful of Aaron’s new paintings, the deep blues and purples of a street that has refused the sun in favor of neon and LEDs instead, where repurposed storefronts and vestigial signs act as a kind of late-Capitalist symbolism.

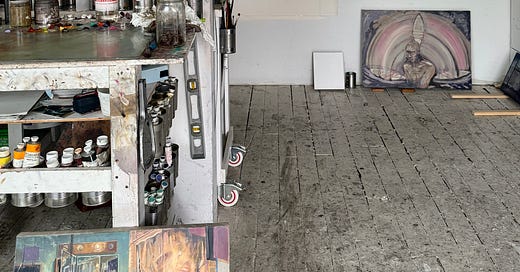

Aaron has two spaces, each quite modest, with thin floor boards that have been painted so many times you wonder whether there’s any wood left. The light is peaceful, the scent is meditative, and Aaron looks weary, like the figures that populate many of his paintings. His figures are elegantly hunched, with expressions so subtle that resentment, love, tenderness, hope, and misery all feel like less than a fraction of a line apart. Aaron is a less severe version of this. He’s friendly and his eyes have more of a spark of immediate kindness. He shuffles through the studio telling me about what he’s been working on and where his mental state is. He shows me little drawings of SpongeBob, drawn dutifully and effortlessly, but where SpongeBob’s normally cracked-out eyes and bucktooth smile would be are instead the world wearied eyes that Aaron tends to favor. This is SpongeBob coming home from work. This is SpongeBob eating ass. This is Spongebob indulging his foot fetish. They are erotic and banal drawings that are both hilarious and oddly moving. They have the pathos I know from Gilbert’s larger paintings, but their speed and simplicity make sure you don’t belabor it. Spongebob needs to get his, just like everybody else.

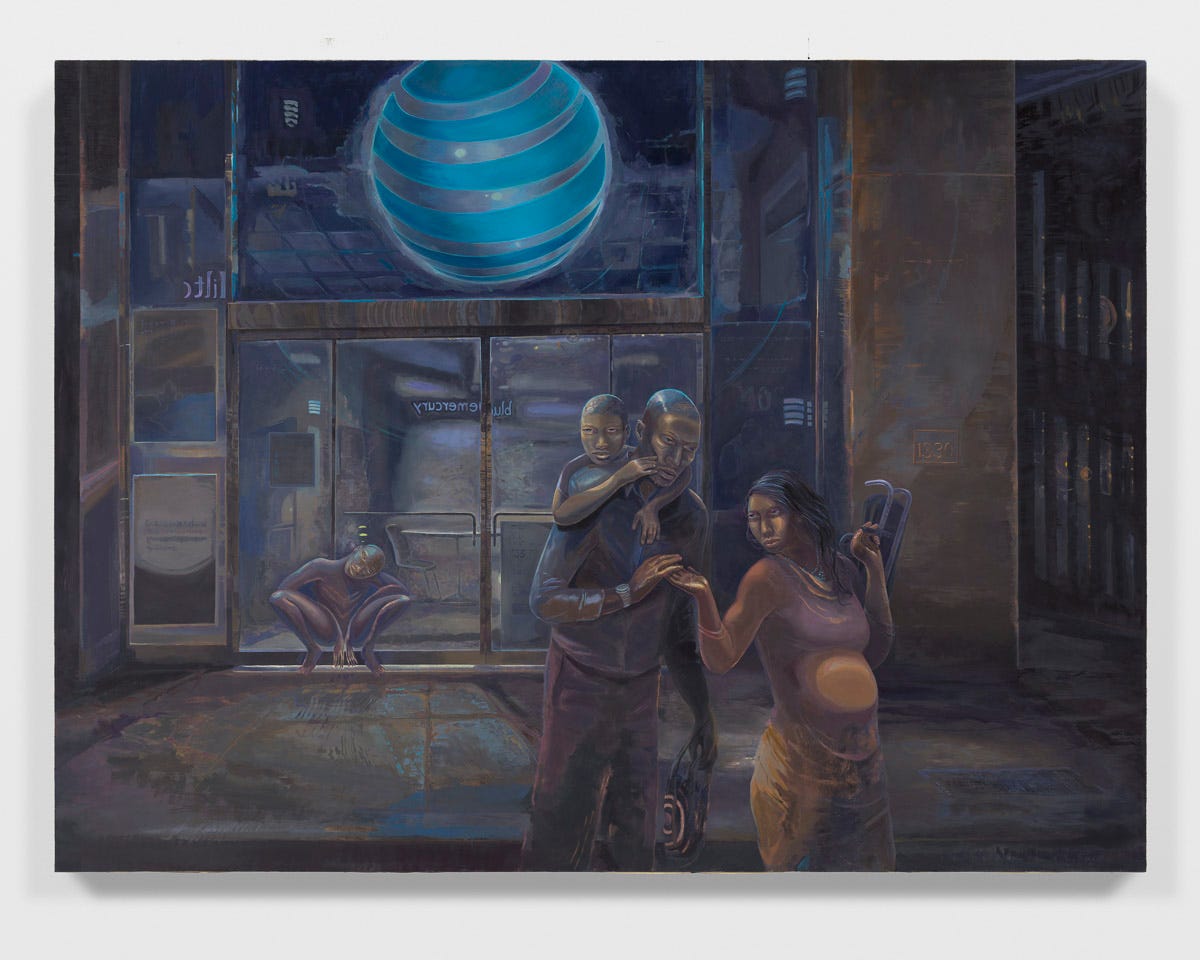

We go over into the other room of the studio where there are a few paintings on the wall. One is so big he has it hung horizontally. He explains to me how he made it in here, which I half understand. On another wall is Pearls (blue mercury), a painting with a family walking past an AT&T store. The little boy hangs off his father’s shoulders with a near mannerist forearm touching his father’s face. The mother is pregnant and has her hand open faced, almost touching the father’s. Her bicep is noticeable. In her other hand is a folded up stroller. They all look like they’ve been up for six days straight. Their mouths are closed and their eyes are shot. It’s Beckett, but it’s material instead of existential; a group instead of singular. They can’t go on, they’ll go on. It’s bigger than philosophy - persistence is deeper than that.

In the back, at the threshold of the store is a being whose head is arched and approaching horror. A ghost, an apparition, a spirit - call it what you want, it’s not a terribly friendly presence. It looks like it wants to play, we just don’t know how it likes to.

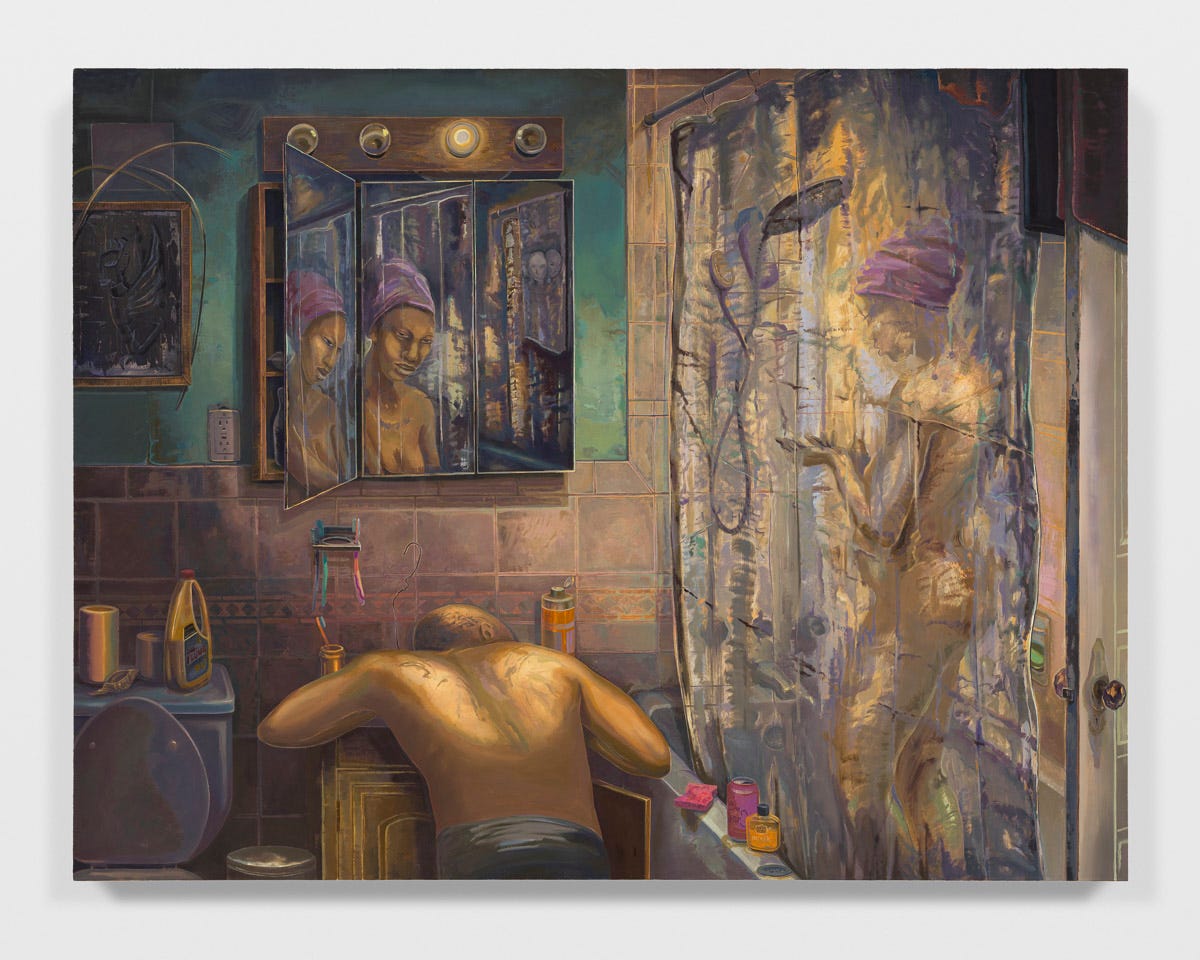

Another painting, The Dream Before, is an interior domestic scene where a man is hunched over the sink, attempting to unclog it with a straightened clothes hanger. A woman showers next to him behind a translucent curtain. We can see her face twice in the three panel bathroom mirror. Her gaze appears different from the two angled mirrors. And the third is the one behind the curtain, where she is absorbed in her own being, looking at her hands. The three panel motif reminds me of religious paintings and feels intentional, as if to say - you can find the spirit here, in a bathroom, with a clogged sink, and a plastic shower curtain. The woman feels anointed. She’s incandescent behind the curtain, where it’s an explosion of painterly play that lights up the figure, but more importantly, there’s a lot of drawing. We can make just enough of her body out to follow the curves of her lips, nose, and buttocks. The lines are charged, erotic. It makes me want more of this line, more of that speed in paintings that are otherwise able to slow anything down. Gilbert’s paintings are profoundly slow, like watching light move in a medium where we can see it moving - where people travel through domesticity and through aeons of history at once.

Aaron tells me he’s been reading Walter Benjamin and thinking about the angel of history. I look for references to Klee, but don’t notice any besides maybe the palette of yellow green glows. But despite thinking about revolution, history, and myth, what I find so strangely confounding about Gilbert’s paintings is their ability to hold hardness and tenderness at once. It is easy to harden a painting - to push people out. But to walk the tightrope, to follow contradictory instructions, this is a specific kind of poetry, one that is historical, philosophical, and genuinely beautiful to look at.

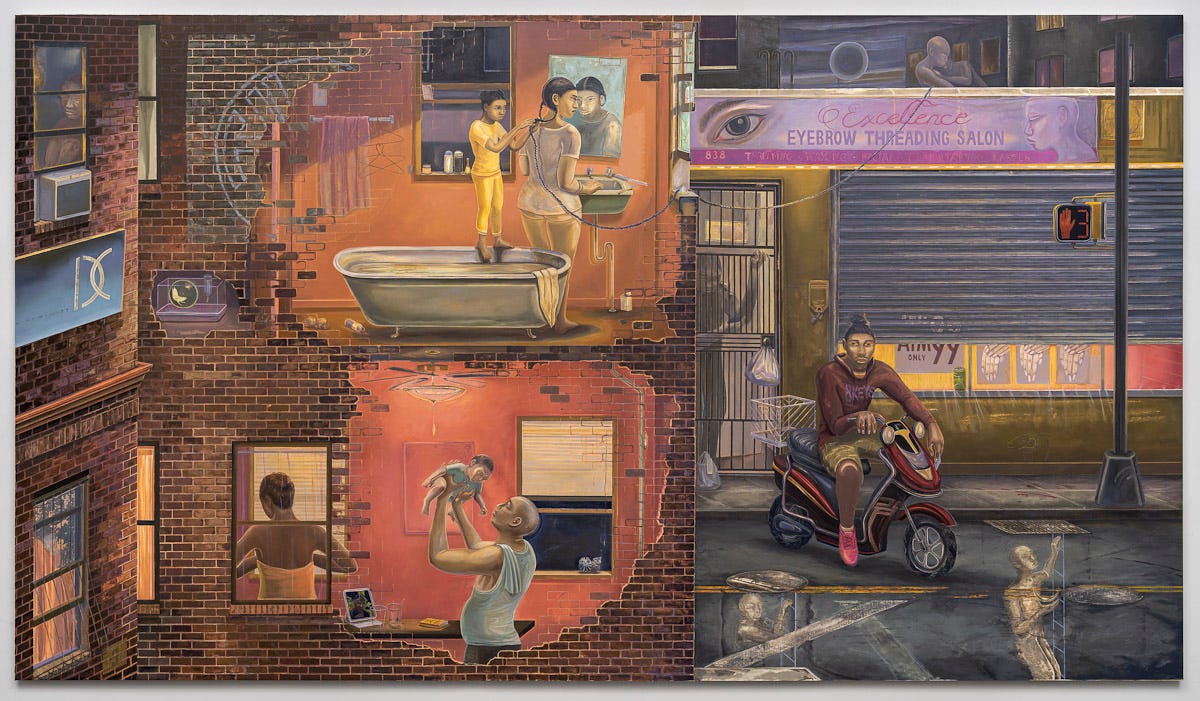

The paintings I saw felt like big swings. They feel mythic and everyday, tableaus of life where people bathe, braid, cook and create. In 8 keys 9 seeds, The ancestors of tomorrow commingle with the spirits of yesterday to make the categories of devotional painting and history painting merge. In • g • o • p • u • f • f •, we see an opening, a break in what feels like a wall of inscriptions, spirits, and past beings. A ghostly Adidas symbol is interrupted by a figure that looks alien, hovering between inscription and depiction. On the opposite side of the opening is a procession of faceless humans while another, who faces them, holds a child. Dim sparkles of the outlines of snakes coil throughout the wall. Everything feels both ominous and magical, portending what lies waiting. Through this opening we see what feels like the present: washed out, cloudy, as if in a haze of atmospheric distraction, with a “go puff” sign for a storefront.

Here, the life of the spirit and the life of history are not separate courses, but one in the same. 8 keys 9 seeds and • g • o • p • u • f • f • both stand as a testaments to Benjamin’s understanding of Messianic time, which was not a conventionally religious temporality in which we are saved by God, but where history redeems itself through revolution, through the past finding its way into the present and made to live again. The resoluteness of the paintings and the figures themselves tell me that this isn’t just a hope, it is simply what is the case - a viewer just needs to believe. After leaving Aaron’s studio, I think I do.